Rodrigo B. Salvador1, Barbara M. Tomotani2, João Vitor Tomotani3, Henrique M. Soares3, Daniel C. Cavallari4, Maira H. Nagai5

1Zoology Unit, Finnish Museum of Natural History, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

2Department of Arctic and Marine Biology, Faculty of Biosciences, Fisheries and Economics, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway.

3Independent researcher. São Paulo, Brazil.

4Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

5Columbia Center for Human Development, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, USA.

Emails: salvador.rodrigo.b (at) gmail (dot) com; babi.mt (at) gmail (dot) com; t.jvitor (at) gmail (dot) com; hemagso (at) gmail (dot) com; maira.nagai (at) gmail (dot) com

The past few years of pandemic and deleterious social media have shown us many things about our societies and our species. Among them, one that struck us particularly hard is how misinformation was spread and how the public’s trust in science – and most other types of research – eroded. We’ve seen anti-maskers and anti-vaxxers, often propped up by asinine and/or unethical leaders telling them to drink bleach or that vaccines could turn people into alligators, and we’ve suffered 7 million deaths due to COVID-19, a grim number that is likely an underestimate. There are complex layers of causes and ramifications surrounding this issue, including the difference between trust in science and trust in science-led policy, but there is one area that we as ordinary researchers can act on – and that is science communication. Engaging with people is one way to build (back) trust in science and experts.

Communicating science to the public is, and has always been, an important part of a researcher’s job. Unfortunately, it is also one that is often neglected. Not out of ill will or lack of interest, mind you, but because researchers are stretched thin by the relentless demands of their core responsibilities of conducting research, mentoring students, and teaching, and also by the time they lose to the Kafkaesque bureaucracy and paperwork that permeates academic life. To many researchers (ourselves and several of our colleagues included), sci-comm often happens in whatever free time is left, making it more of a side task than a priority. That is problematic for many reasons, but we won’t dwell on that because this introduction has already gotten too depressing. What’s undeniable is that, to many researchers, doing sci-comm feels great despite everything else.

Back in 2014, three nerdy graduate students saw the need to start doing some sci-comm of their own. So, we (BMT, RBS, and JVT) got together to write about science in a fun and engaging way. Not just fun for our readers but also fun for us. We felt like simply talking about our own research, or other general new research being published then, things would get very boring really fast. We decided instead that we would bring a pinch of science into our readers’ lives through topics that we love and care about: games, anime, manga, D&D, sci-fi, and anything and everything geeky out there.

So, we started a blog, with simple and short articles. But we quickly realized that it could become something else. The blog was quickly put in the incinerator, and we reshaped our initial idea into an online magazine. Our articles evolved into more than just the quick reads they were and that we usually find online; they became real (and sometimes long) essays, carefully researched, and written with a general audience in mind. As the final touch, we stole the looks and feels of academic journals, and we became the Journal of Geek Studies.

Our first official volume was published on December 10, 2014, with five (and we must confess, rather raw) articles, all written by ourselves. From our second volume onwards, we began to reach out to other experts to write for us. Slowly throughout the years, we managed to attract authors from several corners of the planet and achieved a reasonable diversity. To us, a significant achievement was to attract many people from outside the Anglosphere. Our content is, of course, entirely in English, even though we are not native speakers ourselves. English is, whether we like it or not, the lingua franca of science and the way we had to reach as many people as possible around the globe.

Along the way, we also started to conduct interviews with game developers, as well as other scientists somehow involved in geek stuff. We also brought in three new members to our editorial board at different times (HMS, DCC, and MHN) who increased our overall geekiness level and (fictional) impact factor to over nine thousand.

We’ve had some very interesting stories to tell from those ten years of spreading knowledge and geekiness (not necessarily in that order!). For instance, we were contacted by people that worked in the movie industry because of our Ant-Man and “zombie model” articles. The results from our “metal birds” article were featured on Nature’s website – that is one of the most prestigious scientific journals out there! We coined and defined the term “Astolfo Effect”, which is becoming more well known on the Internet, even outside the Fate community. Other curiously popular articles in terms of access were the one telling the story of how the Ancient Egyptian god Medjed became popular in Japan, and the one discussing whether mechas (Japanese giant robots) are isometric or allometric.

And we’ve come a long way. So far, we published 129 articles (okay, perhaps with one easter egg among them), contributed by 93 authors based on 23 different countries, representing over 70 universities and research institutions worldwide. Our articles have been accessed over a half a million times by people from 214 different countries. Most of our readers are based in: (1) the USA; (2) Brazil; (3) UK; (4) Canada; (5) Australia; (6) Philippines; (7) Germany; (8) India; (9) Indonesia; (10) Japan.

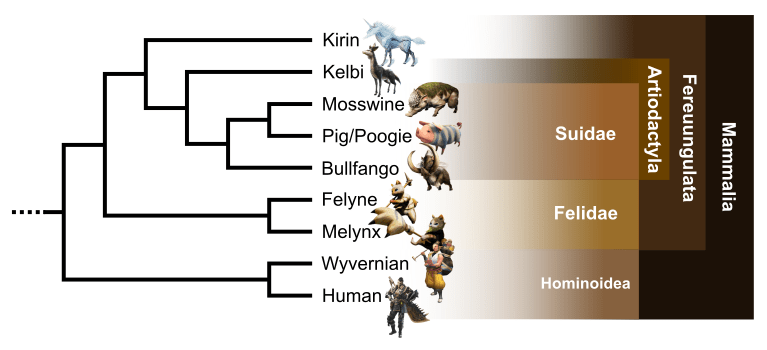

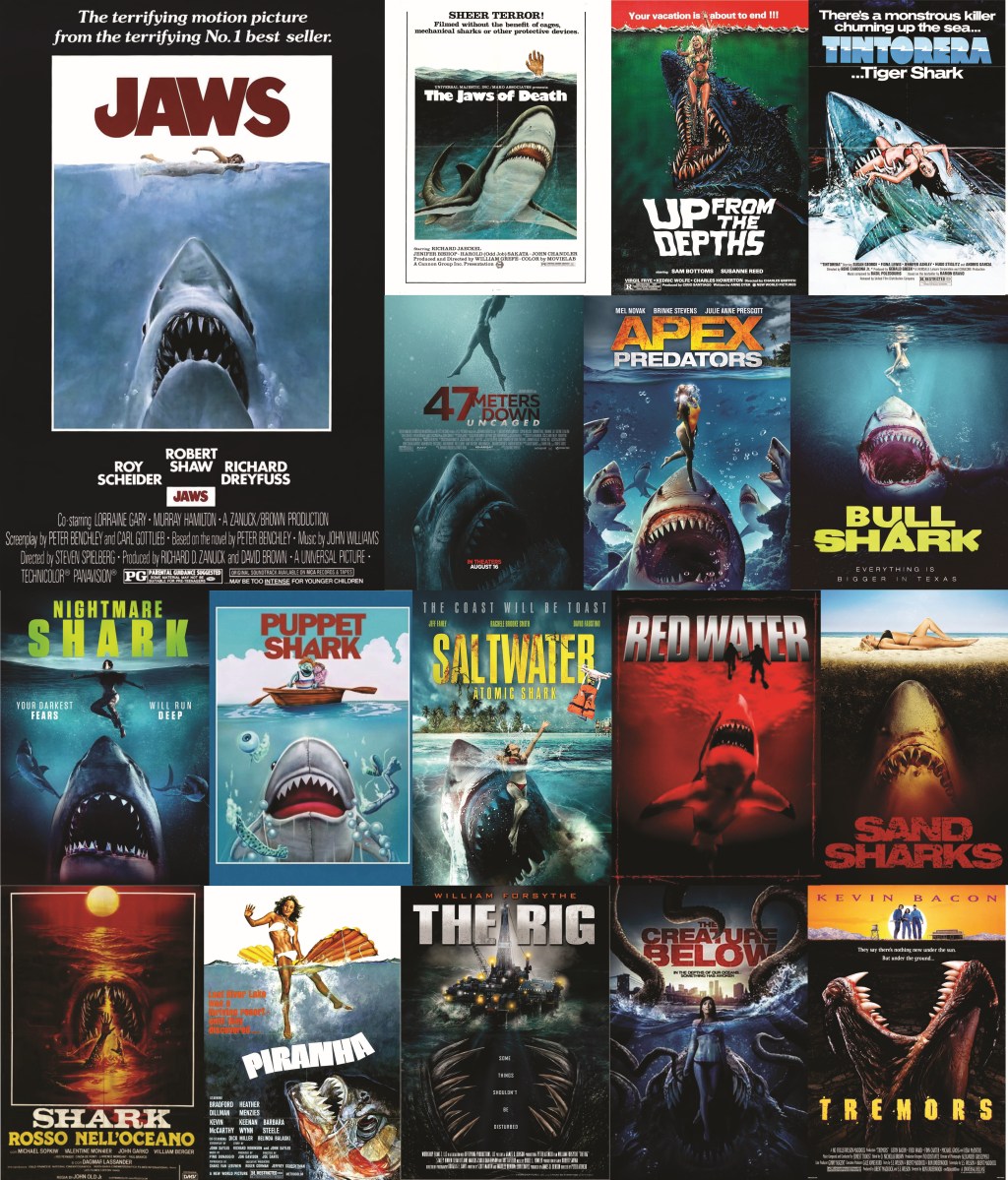

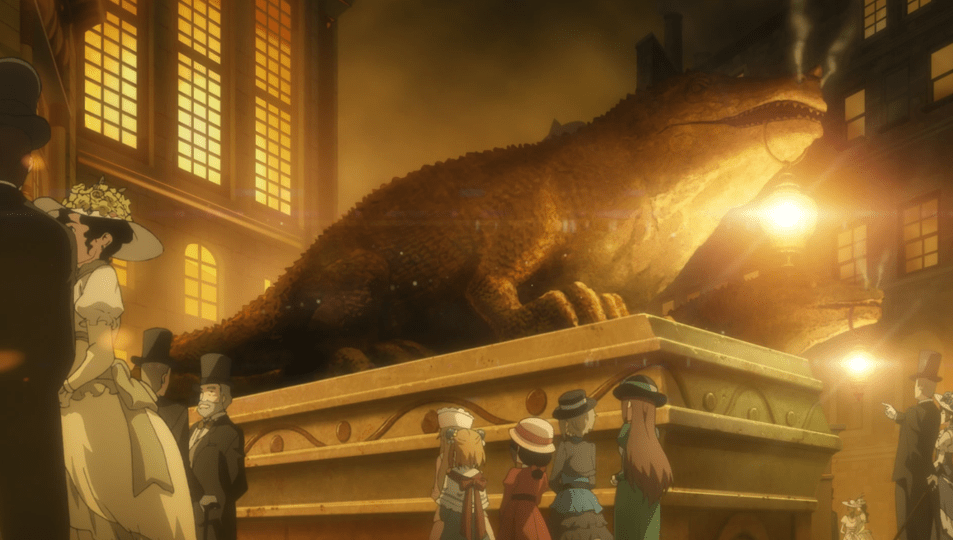

Among our published articles, most, by far, belong to Biology. More than half of our articles (70 to be more precise) are related to the biological sciences and the majority of those belong more specifically to the field of Zoology. History and Archaeology combined are a distant second place, with 26 articles. The most discussed geek “area of knowledge”, also with more than half our articles, is Video Games, summing up to a whopping 74 articles. Once again, a distant second is Cinema, with 29 articles. Among the most specific topics, the first place belongs to Pokémon, with 22 articles. We think it’s safe to say we probably became the biggest authority on “Pokémon taxonomy” thanks to that.

The day this article is being published marks the 10th anniversary of the Journal of Geek Studies. We have come quite far since our humble beginnings and we have only you to thank for, our readers, our authors, and our interviewees. Thank you for sticking with us. It doesn’t matter if you have just discovered the Journal, or if you knew us before we were cool; either way, we are sincerely grateful. You folks are the reason we do this, so we hope you had some fun reading our articles – and maybe (why not?) also learned something new along the way. If we managed to garner a little more trust in science, even better. So, let us celebrate our anniversary and wish for another 10 years of geeky sci-comm.

EDITOR’S CHOICE ARTICLES

Below we present our Editor’s Choice Articles. Each editor picked one article from the entirety of the Journal’s archives – that was not their own, of course. The choice was not based on scientific merit or anything serious like that – they’re just our favourite articles, for personal and perhaps unexplainable reasons.

RBS’s choice: Frankenstein, or the beauty and terror of science – by van den Belt, 2017.

BMT’s choice: An unexpected bird in Honkai: Star Rail and China’s war on sparrows – by Salvador, 2023.

JVT’s choice: Playing with the past: history and video games (and why it might matter) – by McCall, 2019.

HMS’s and DCC’s choice: The Astolfo Effect: the popularity of Fate/Grand Order characters in comparison to their real counterparts – by Tomotani & Salvador, 2021.

MHN’s choice: Cicadas in Japanese video games and anime – by Salvador, 2022.

REFERENCES

Andrews, E.; Weaver, A.; Hanley, D.; et al. (2005) Scientists and public outreach: participation, motivations, and impediments. Journal of Geoscience Education 53: 281–293.

Bennett, M. (2020) Should I do as I’m told? Trust, experts, and COVID-19. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 30: 243–263.

Caplan, A.L. (2023) Regaining trust in public health and biomedical science following Covid: the role of scientists. Hastings Center Report 53(S2): S105–S109.

McCall, J. (2019) Playing with the past: history and video games (and why it might matter). Journal of Geek Studies 6: 29–48.

Salvador, R.B. (2022) Cicadas in Japanese video games and anime. Journal of Geek Studies 9: 91–100.

Salvador, R.B. (2023) An unexpected bird in Honkai: Star Rail and China’s war on sparrows. Journal of Geek Studies 10: 49–57.

Salvador, R.B.; Tomotani, B.M.; O’Donnell, K.L.; et al. (2021) Invertebrates in science communication: confronting scientists’ practices and the public’s expectations. Frontiers in Environmental Science 9: 606416.

Tomotani, J.V. & Salvador, R.B. (2021) The Astolfo Effect: the popularity of Fate/Grand Order characters in comparison to their real counterparts. Journal of Geek Studies 8: 59–69.

van den Belt, H. (2017) Frankenstein, or the beauty and terror of science. Journal of Geek Studies 4: 1–12.

World Health Organization. (2024) WHO COVID-19 dashboard. Available from: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=o (Date of access: 09/Nov/2024).

The editorial team

Dr Rodrigo B. Salvador is a biologist and curator at the Finnish Museum of Natural History and current editor-in-chief of the JGS. He specializes in biodiversity research of land and freshwater snails and spends a good portion of his time thinking up geek culture-based scientific names for the new species he discovers, such as Gallirallus astolfoi, Halystina umberlee, and Idiopyrgus meriadoci.

Dr Barbara M. Tomotani is a biologist, bird fanatic, and researcher at the Arctic University of Norway. She is living in the Arctic and studies how animals adapt to the weird (lack of) daylight in the region, while at the same time, tries to adapt to it herself. In the present, she has way less time than she wished for geek stuff, but she tries to compensate that by sneaking Pokémon quizzes in her teaching and exam questions whenever she can.

João Vitor Tomotani, MSc, is an engineer that currently works with Data Analytics applied to Supply Chain. When he is not busy building and analysing dashboards, he is thinking of how he could apply all that to more interesting themes or running while listening to geeky podcasts. He is also kind of a weeb, being a manga and JRPG enthusiast.

Henrique M. Soares is an engineer applying machine learning and data engineering in the industry. He is fascinated by applications such as computer vision and language processing and has a rather mixed view on how artificial intelligence will impact society. When he is not fretting over thoughts about doomsday machines ending society as we know it, he likes to play all kinds of RPGs and tactics-style games accompanied by his dog, Kepler.

Daniel C. Cavallari, MSc, is a biologist and lab technician at FFCRLP, University of São Paulo, Brazil, with a passion for studying molluscs, especially gastropods, whether they call the sea or land their home. When he’s not busy with research, Daniel is deep into RPGs of all kinds. As a dedicated DM, he has a particular fondness for naming his most extravagant NPCs after famous taxonomists. After all, why not bring a bit of scientific flair into the fantasy world?

Dr Maira H. Nagai is a biologist and scientist at Columbia University, currently contemplating the beauty of the development of epithelial airways. Her mind is constantly (and sometimes unbearably) filled with thoughts on how things come about, no matter whether it is for work, for fun, or to ease her plaguing existential questions. She is proof that you don’t necessarily need to be a geek to be amused by geek stuff – just need some appreciation of wit, respect for fastidiousness, and curiosity about the world.