Olivia Le Moëne

Independent researcher. Uppsala, Sweden.

Email: olivia.lemoene (at) gmail (dot) com

Hergé’s Tintin comic books are a classic of graphic literature that needs no introduction. Among his most charismatic characters are the detectives Thomson and Thompson (Dupont and Dupond in the original), or Thom(p)sons. The policemen with their timeless dress style and almost identical appearance are present in the majority of Tintin’s adventures. They first appeared in Cigars of the Pharaoh (1932–1934) under the name X33 and X33A (X33 bis in the original), then were renamed “Thomson and Thompson” in King Ottokar’s Sceptre (1938–1939). It is only in The Crab with the Golden Claw (1940–1941) that they are differentiated for the first time: Thompson is the policeman with the straight moustache, and Thomson the one with the curved moustache. In creating the detectives, Hergé was inspired by his own father Alexis Rémi and his twin brother, Léon, who liked to underline their physical resemblance by wearing similar clothing and accessories (Sadoul, 1989).

All along The Adventures of Tintin, the Thom(p)sons serve a humorous role, and are characterized by their clumsiness, both gestural and verbal. They also represent a satire of the police or public authorities (Delpérée, 2014), leading absurd reasoning and failing to make logical deductions or to keep information secret. While they regularly suspect innocent people, they also blindly believe real criminals.

Despite their thorough presence in the books, few elements of the Thom(p)sons’ lives are known. They are familiar with each other, they address each other informally, have known each other for at least 7 years (The Black Island, p.37, C3) and refer several times to their “home” (The Secret of the Unicorn, p.2, A4, and p.32, B3), suggesting that they live together. They work for “Scotland Yard [la Sûreté]” (The Black Island, p.2, B3), although they are occasionally recruited by Interpol (Red Sea Sharks, p.9, C5). No information is known about their family, which, to many tintinophiles, echoes Hergé’s unknown paternal grandfather (Peeters, 2006). Indeed, the theme of identity, or rather its ambiguity, is very present in The Adventures of Tintin (Bidaud, 2017). For example, various criminals usurp and exchange identities: the dishonest twin brother of Professor Alembick, Rastapopoulos disguised as Marquis Di Gorgonzola, a fake Prof. Calculus fooling Prof. Topolino. Some characters only have a partial identity due to their lack of first or last name, while Captain Haddock leads a mythical quest after his ancestor (and lookalike!) the Chevalier de Hadoque. When studying the Thom(p)sons, the theme of identity and that of lack of filiation is pivotal; for the simple reason that they look like twins, while having different surnames, thus they cannot be siblings. The question of the origin and kinship of the Thom(p)sons has been troubling Tintin readers since very early on, somewhat overshadowing that of their differentiation. Indeed, the Thom(p)sons are identical apart from their moustaches, but what about their personality? Based on the study of the Thom(p)sons’ speech corpus and their actions across The Adventures of Tintin, this article proposes to quantify their differences in order to finally elucidate the respective identity of Thompson and Thomson.

METHODS

Book selection

The data presented in this article are based on 17 out of the 24 Adventures of Tintin. The last book, unfinished, Tintin and Alph-Art is not accounted for. In Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, Tintin in the Congo, Tintin in America, The Shooting Star, Tintin in Tibet, and Flight 714 to Sydney, the Thom(p)sons either do not appear, or do not say or do anything significant. These books are therefore excluded from the analysis.

Many changes have been made to the books throughout the reissues. This study is based on book reissues published between 2006 and 2007, which are referenced at the end of the article (Hergé, 1930, 1931, 1932, 1934, 1936, 1937, 1938, 1939, 1941, 1942, 1943, 1945, 1948, 1949, 1950, 1953, 1954, 1956, 1958, 1960, 1963, 1968, 1976, 1986). When a specific comic book box is mentioned, it is referred to by the page number where it is found, the letter corresponding to the strip it is in (from top to bottom) and the number of the box in the strip (from left to right). For example, the Thom(p)sons are introduced to king Muskar XII in King Ottokar’s Sceptre in page 42, strip B, box 1 (p.42, B1).

Importantly, the results presented here are based on the analysis of the French version of the comics, which is Tintin’s original language. Therefore, it is likely that, should this analysis be re-conducted based on the English translation, results would slightly differ.

Data collection and categorisation

A statement is defined as a speech bubble, in a box. The statement is associated with its emitter, Thompson or Thomson, on the basis of the shape of the speaker’s moustache, and with an interlocutor. The order in which the Thom(p)sons speak within a box is also noted.

Bubbles containing only punctuation marks are omitted from the analysis, and so are those whose emitter is not identifiable or physically distinct. This latter case corresponds to 79 statements. The final corpus contains 928 statements, which differs slightly from the corpus established by Meyer (2007), which contains 1001 statement from an identifiable emitter.

The text corpus of each Thom(p)son is composed of all his statements. The occurrences of the famous expression “je dirais même plus” translated to “I would even say more” or “to be precise” (TBP) are counted. The quantification of lapses, or slips of the tongue, is based on the analysis by Meyer (2007). Recurring interlocutors are defined as characters who are spoken to by both Thom(p)sons, at least once.

Comedy

The Thom(p)sons are famous for their clumsiness and the comedy effect it induces. These acts are categorised as either: falls (drawn or suggested, ex: falling off the stairs), clumsiness causing benign pain (ex: collision with a pole); and other situations that ridicule the Thom(p)sons (ex: inappropriate disguise in a foreign country).

All acts are quantified per Thom(p)son and per book. When gags were spun over multiple boxes, they were counted as a single occurrence. Finally, when one Thom(p)son causes harm to the other through clumsiness, the gag is attributed to him, and not to the injured Thom(p)son.

Laterality

Object handling was annotated for each Thom(p)son to record the hand used and the object grasped, in order to determine laterality and preferred tasks. Cases in which the Thom(p)sons were not distinguishable were excluded. When an object is hung on a Thom(p)son’s arm (e.g., cane or coat), but not grasped, or when an object is grasped with both hands, those occurrences are also excluded from the analysis.

Objects used less than 20 times in total are grouped into categories: papers (arrest warrant, newspapers, books, letters, envelopes, telegrams), packages (parcels, packages, boxes), drinks (glass, beer), and social (handshakes and other social contacts, including with Snowy). A category “tools and accessories” included: boats, pockets, stair ramp, ropes, cars, sticks, jerricans, banknotes, lighters, pills, car hoods, cigarettes, keys, cushions, nets, fans, binoculars, magnifying glasses, coats, blackjacks, handcuffs, watches, umbrellas, shovels, pendulums, coins, door handles, wallets, skeletons, tobacco, test tubes, pipes, and suitcases.

It should be noted that this quantification should be considered with caution, since the scoring was done per box. For this reason, when the same object is present on several pages in a row, it is counted many times, artificially increasing the use of the hand holding it. However, many inversions are also present in-between the boxes, justifying this method of quantification.

Statistical analysis

For each measured parameter, the percentage attributable to each Thom(p)son is calculated per book. In case of complete absence of the parameter in a book, a value of 0 was attributed to each Thom(p)son. The percentages shown in the results are the mean of the percentages calculated by book, by Thom(p)son.

The raw data of the number of speech bubbles, of bubbles read first, of interlocutors, of initiated dialogues, of comic acts, percentage of hand usage and frequency of speech disturbances, were analysed with Wilcoxon tests for non-parametric data. The distribution of recurring interlocutors between the Thom(p)sons is tested with a Fisher’s test, and the distribution of comic acts and object handled with the χ2 (chi-squared) test.

The figures and analyses were obtained with RStudio 2024.09.0 and R 4.4.1 (tidyverse package). The Thom(p)sons’ speeches were analysed with word cloud with the help of iramuteq version 0.7 alpha2 (30 UCE, core French dictionary).

Statistical significance threshold is set at 5% (p-value < 0.05). A trend is defined by p-value < 0.10.

RESULTS

Speech distribution

During the Adventures of Tintin, the Thom(p)sons emitted 928 speech bubbles whose emitter was unambiguously identifiable. Of these, 405 belonged to Thompson, and 523 to Thomson. On average across the Tintin books, Thompson expressed 43.58% of the bubbles, and Thomson 56.41%. The preponderance of Thomson’s speech over Thompson’s is statistically significant (Wilcoxon test, V = 98, p = 0.033). Thompson speaks more often than Thomson in only 3 of the 17 albums, starting from Destination Moon (Fig. 2A).

Bubbles formulated by Thompson are read first either when he is the only one speaking in a box, or when he speaks before Thomson, which corresponds to 62.63 ± 6.49 % of his text corpus. For Thomson, the proportion of bubbles that are read first is higher (79.41 ± 4.84 %). Across the 17 books analysed here, bubbles read first belong significantly more often to Thomson (V = 113.5, p = 0.020), even though this effect fades, or even disappear from Destination Moon (Fig. 2B).

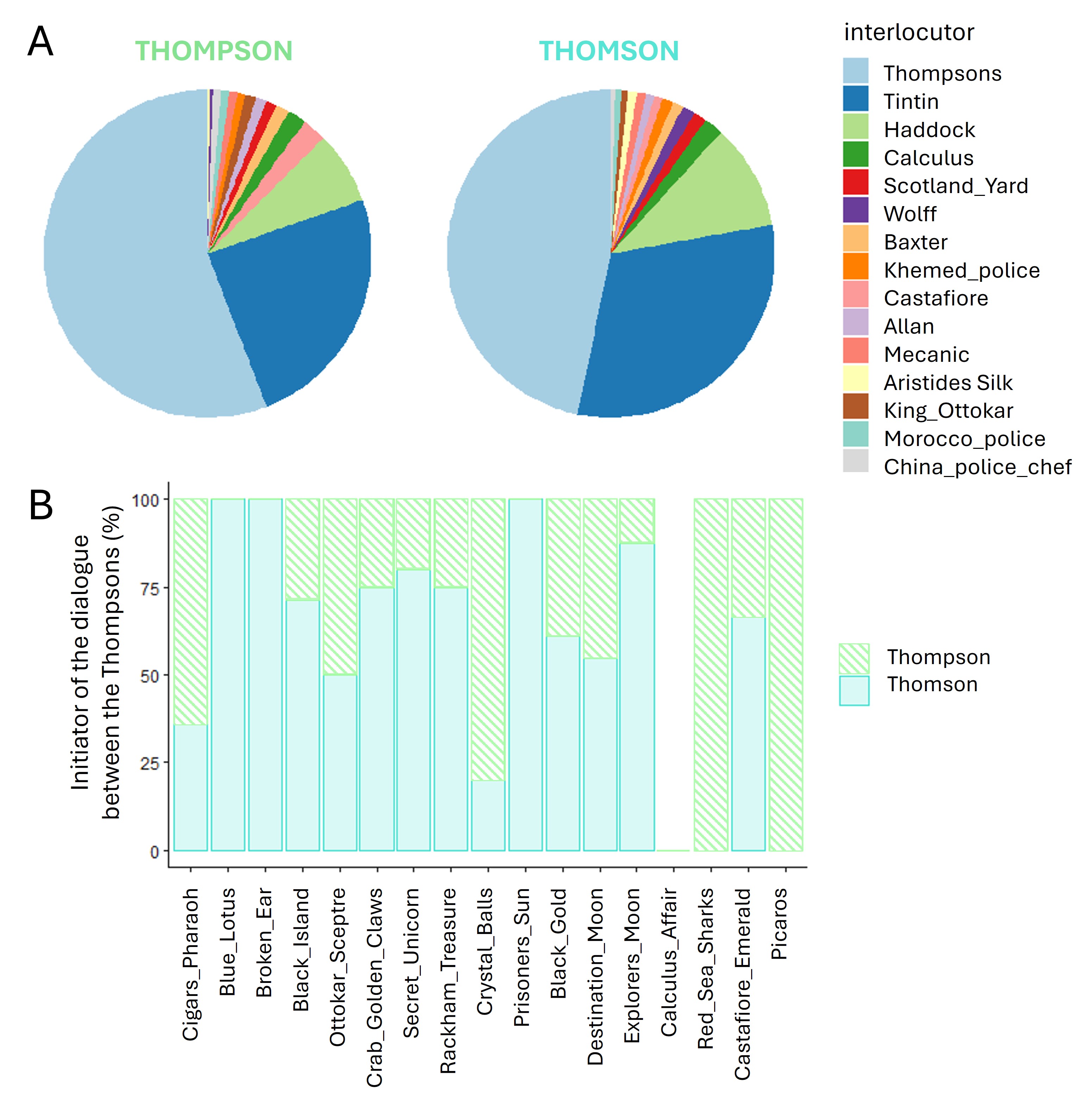

Interlocutors

In the 17 Tintin books in which the Thom(p)sons are significantly present, there are 55 different interlocutors, 34 for Thompson and 49 for Thomson, including 28 in common. The main interlocutor of each Thom(p)son is the other Thom(p)son, with 428 bubbles (46.12 %) of the total corpus directed towards one of the Thom(p)sons.

The number of interlocutors per book is similar for both Thom(p)sons, although there is a slight tendency towards a larger number of interlocutors for Thomson (V = 12.5, p = 0.072). Indeed, on average over the albums, Thomson talks to 89.78% of the total number of interlocutors, and Thompson to 76.36%.

Fifteen recurring interlocutors were identified, the most frequent besides the Thom(p)sons being Tintin, Captain Haddock, and Professor Calculus. Speech is addressed to these recurring interlocutors uniformly, regardless of the speaking Thom(p)son (Fisher’s Exact Test, p = 0.203) (Fig. 3A).

Inter- Thom(p)sons dialogues are characterized by a stronger initiation by Thomson. Thomson is the initiator of the exchange and Thompson the respondent in 62.22% of the dialogues (Fig. 3B). This initiation rate biased in favour of Thomson does not, however, reach statistical significance (V = 27, p = 0.064). Notably, Thompson initiates 100% of the dialogues in Red Sea Sharks and Tintin and the Picaros.

Bubbles content

Thompson and Thomson are well known for their characteristic elements of language, in particular the repetition of the expression “I would say even more”/”to be precise”, or the frequency of their slips of the tongue and other speech disturbances. During the Adventures of Tintin, Thompson utters the expression “to be precise” (hereinafter TBP) 38 times, and Thomson only 20 times. Across the 17 books, Thompson tends to use this expression more often (V = 32.5, p = 0.065). On the other hand, slips of the tongue are made by both Thom(p)sons at the same frequency (V = 31, p = 0.758). The data taken from Meyer’s article (2007) show that Thompson is responsible for 32.22 ± 9.76% of slips of the tongue during the albums, and Thomson for 38.37 ± 10.33%.

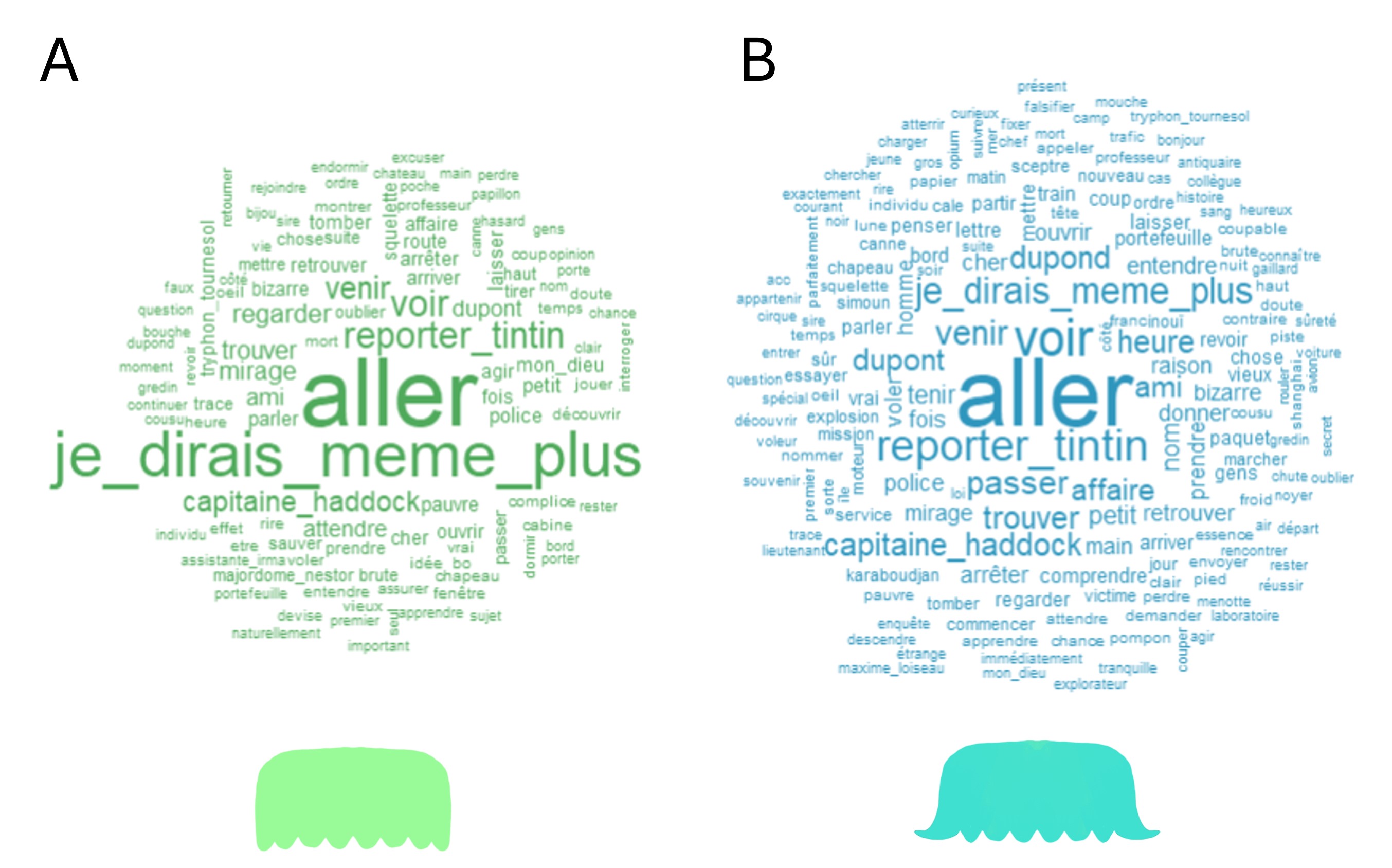

The representation of the text corpus of each Thom(p)son by word cloud highlights a smaller lexicon for Thompson, and the high frequency of the expression TBP (Fig. 4A). For both Thom(p)sons, the most frequent interlocutors “captain_Haddock” and “reporter_Tintin” were represented, as well as several verbs characteristic of their detective work: “aller” [go], “voir” [see], “trouver” [find], or “regarder” [look] (Fig. 4).

Comedy

The legendary clumsiness of the Thom(p)sons contributes to the recurring situational comedy that accompanies their interventions. The vast majority of the comic episodes are common to both Thom(p)sons: the fall of one is followed by the fall of the other. This is visible in the distribution of comic actions between them: Thompson accumulates 23 falls, 37 clumsy acts, and 57 other gags. Thomson makes 24 falls, 43 clumsy acts, and 62 other comic actions (c2 = 0.096, p = 0.953) (Fig. 5). Despite this similarity, a slight trend emerges over the books towards a greater number of comic acts attributed to Thomson (V = 31, p = 0.075). This trend is particularly visible when looking at the distribution of non-common comic actions, which are more often due to Thomson (Fig. 5D).

Laterality

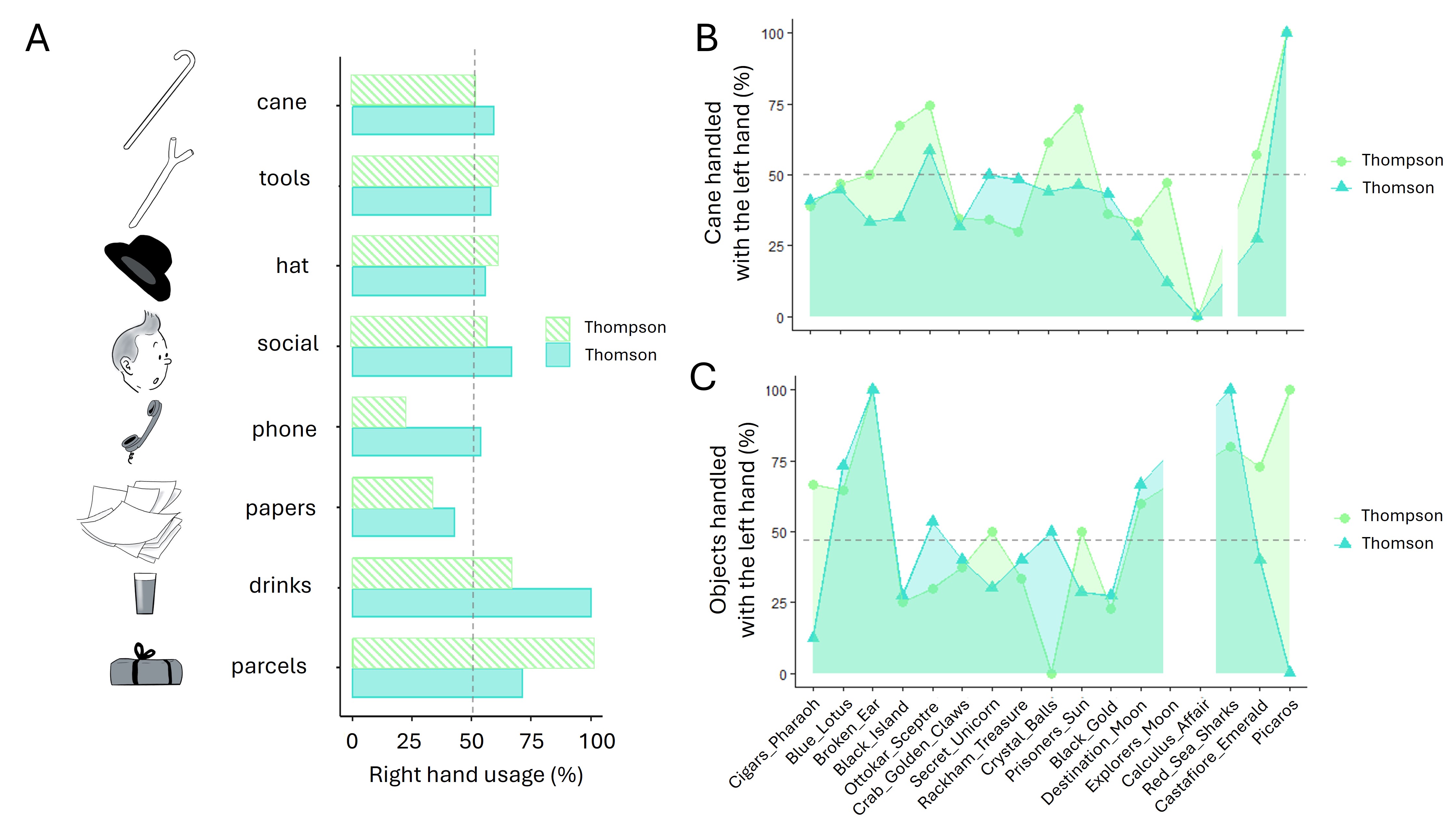

Throughout the Adventures of Tintin, the Thom(p)sons handle 67 different objects or people. Firearms are systematically held with the right hand for both Thom(p)sons, and so are pens. In addition, only Thompson drives (in Land of Black Gold and in The Calculus Affair).

To handle the most frequently used objects, both Thom(p)sons mainly use their right hand (Fig. 6A). The most frequently grasped object is their cane (395 times for Thompson, 476 times for Thomson). By comparison, the second most characteristic object of the Thom(p)sons, their hat, is grasped only 41 and 34 times by Thompson and Thompson, respectively. The different types of objects are handled by both Thom(p)sons uniformly (c2 = 7.159, p = 0.413).

In the books, we observe that to grasp their cane, Thompson uses his left hand more often than Thomson (in 49.04% vs 40.20% of the cases respectively; V = 83, p = 0.060) (Fig. 6B). However, when combining all objects (excluding canes, firearms, and pens), no difference in lateralization appears between the Thom(p)sons (V = 21.5, p = 0.328) (Fig. 6C).

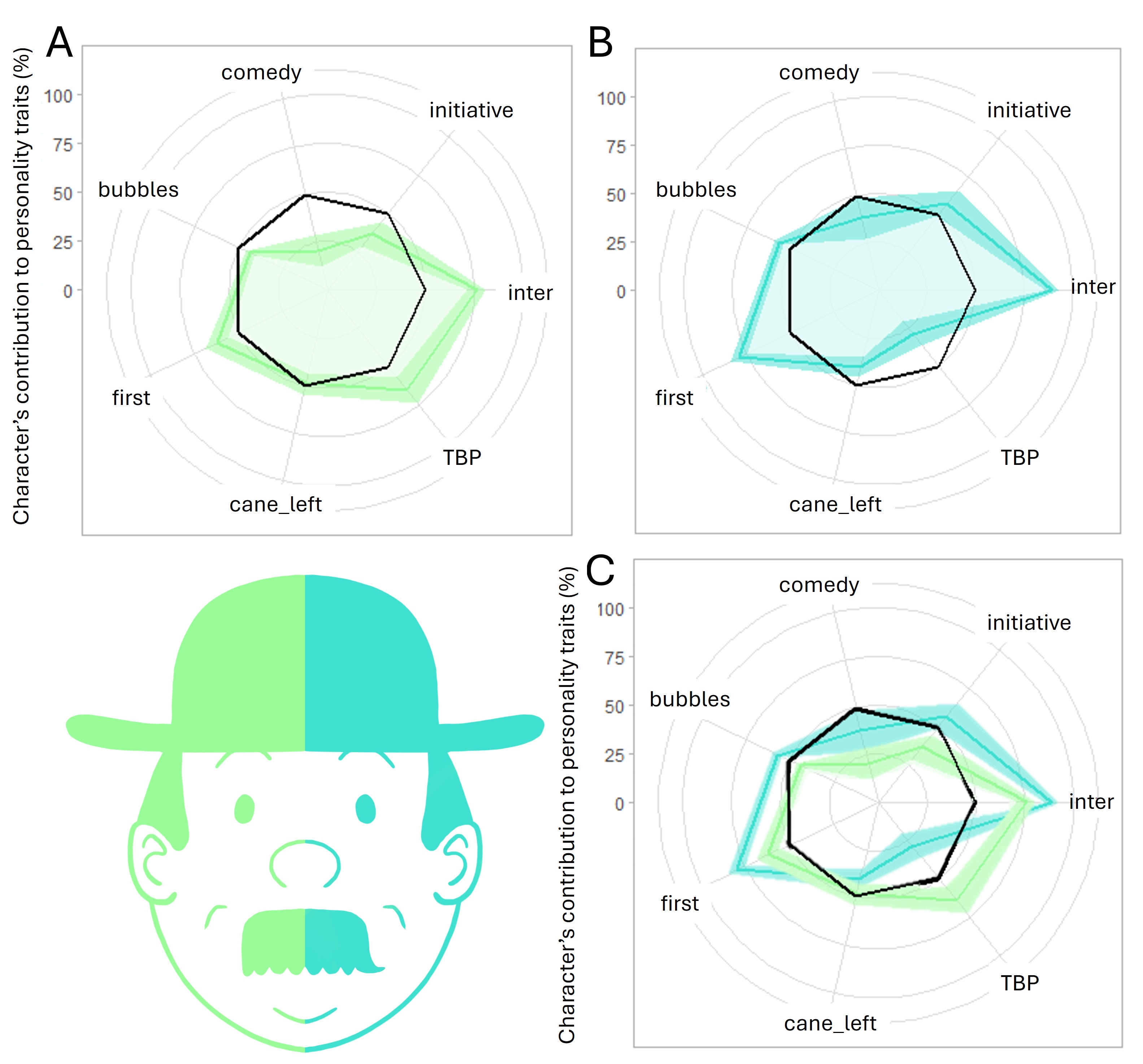

Individual profiles of the Thom(p)sons

The parameters analysed above capture key elements of the personality and behaviour of each of the Thom(p)sons. The average percentage of each parameter, for each Thom(p)son, is represented in a radar profile in Figure 7.

DISCUSSION

The Adventures of Tintin have been the subject of a plethora of analyses by tintinophiles and tintinologists. However, within the body of work discussing the characters of Tintin, Thompson and Thomson have been the subject of (too) little consideration. Although several books have dealt with the Thom(p)sons, within tintinophiliac (Groensteen, 2006) or medical studies (Bonnemain, 2005; Castillo, 2011; Bidaud, 2017), very few have dealt with the Thom(p)sons specifically, at the exception of the excellent Le Dupondt sans Peine (Algoud, 1997). Therefore, this paper is, to the author’s knowledge, the first one investigating the quantifiable difference in personality between Thompson and Thomson.

In the present study, the word clouds from each Thom(p)son’s corpus highlight the similar role of the Thom(p)sons in The Adventures of Tintin, namely their relative passivity in the investigation, with the preponderance of the verbs “come”, “see”, “go”, “look”, “find”, and “leave”. Rather than actively investigating, the Thom(p)sons make an “act of presence”. Regarding the laterality of the Thompsons, rumours have circulated suggesting that one was right-handed and the other left-handed. On the contrary, the data collected here show that both Thom(p)sons are right-handed, they only use their right hand for aiming and writing, and still use it preferentially to manipulate most objects.

It is the analysis of the text corpus and the actions of the Thom(p)sons that clearly shows their difference: Thomson appears more extroverted; he talks more, frequently takes the initiative, has more interlocutors, and commits more unique comic actions. On the contrary, Thompson is more withdrawn, often serving as a support to Thomson, responding to and emphasizing his statements, notably through the expression “to be precise”. Finally, even though poorly, only Thompson drives, and he seems to handle his cane with ambidexterity.

It is interesting to note that these trends, confirmed in almost all the books, are reversed in the last Tintin books, starting with Destination Moon (1956). Thompson then seems more extroverted than Thomson. This inversion in their personality could be deliberate on Hergé’s part, supposedly out of concern for fairness between the Thom(p)sons or out of weariness with their usual dynamic. At the same time, it is precisely in the last Tintin books that we originally find inversions in the Thom(p)sons’ names. These errors were acknowledged by Hergé and corrected in the reissues. We initially find inversions in Destination Moon (p.24, B3), Red Sea Sharks (p.7, D2), The Castafiore Emerald (p.58, D1), or Tintin and the Picaros (p.60, A2). This list (potentially not exhaustive, due to the author’s difficult access to the original editions) suggests that the reversal of the Thom(p)sons’ role in the books is effectively accompanied by a confusion in their names by Hergé.

The role of the Thom(p)sons in The Adventures of Tintin is often limited to their humorous scope, or to the highlight of Tintin’s impressive skills. However, even if this is rare, the Thom(p)sons also make the investigations progress, when their police master key allows doors to be opened (Cigars of the Pharaoh, p.57, D1) or when they partially elucidate the theft of Ottokar’s sceptre (p.43, A2–B1). While the lucidity of their reasoning in King Ottokar’s Sceptre surprises the readers, they themselves judge this case to be “childishly simple” (p.42–43). On the one hand, Tintin is logical, capable of quick deductions and of influencing geopolitical decisions (Land of Black Gold, p.35–36), but has a forever juvenile physique. On the other hand, the Thom(p)sons have a stark physique, marked with age with a partial baldness under their hats. Unlike Tintin, the Thom(p)sons act immaturely despite their age.

The recurring characters of Tintin form together “the Moulinsart family”: an adopted family, rebuilt by characters without history or family ties (Bidaud, 2016). In this context, one can wonder about the role of the Thom(p)sons within this family. Vexed by yet another recommendation from Tintin in The Castafiore Emerald (a recommendation that they will obviously fail to follow), they exclaim “We are not children anymore!” (p.39, D3). And yet… they systematically address each other informally, which is different from all the other adult characters in Tintin (in French), and we see them sleeping in the same room in Prisoners of the Sun (p.10, A3–C3), just as children would. Terribly naive and displaying a somewhat lacking general culture, their credulity and their multiple episodes of clumsiness (a glorious total of 246 comic incidents over the course of the 17 books analysed here) reinforce their childish side. They are scolded by Tintin for their bickering about bedding in Red Rackham’s Treasure (p.16, D1) who asks them “Aren’t you ashamed, at your age?”. Earlier, in the same book, Professor Calculus is surprised by their clumsiness which he interprets as “childishness” (p.8, B2). Finally, their statement “We have had moustaches since our early childhood!” in Tintin and the Picaros (p.47, C1) suggests either that they have changed very little since childhood, or even that they have not emerged from it yet.

The ambiguous identity of the Thom(p)sons contributes to their infantilization. It appears that the individual personality of each Thom(p)son is not yet crystallized, since the trends are reversed over the course of the books. They themselves hesitate between fusion, through physical and behavioural resemblance, and differentiation, by emphasizing the difference in their surnames and their unequal verbal interactions (Bidaud, 2017). The fact that Hergé himself confused them in some strips raises a smile: the Thom(p)sons are reminiscent of twins playing on their resemblance, to the point of successfully misleading their own parent.

Laterality scoring highlights two representations of the Thom(p)sons: either as doubles or as mirror symmetries. Once again, the Thom(p)sons appear to be prisoners of their status, either as the same or the reverse of the other, they can only exist by comparison to each other. A previous analysis of the Thom(p)sons’ text corpus suggests that their co-existence hides a rivalry: the incorrect repetitions of the other’s speech actually serves as a mechanism of self-affirmation (Meyer, 2007). The data reported here suggest that Thomson is the most present in the books, while Thompson strives to exist alongside him, by repeating what he says, or through emancipation by driving.

Finally, the Thom(p)sons become physically indistinguishable on two occasions: at the end of the Land of Black Gold due to the ingestion of N14 which mutates their hair system, and during a relapse in Explorers on the Moon. Thus, despite their extreme physical resemblance and similarity in behaviour, it is the disease that makes them indistinguishable. We could therefore conclude that a healthy Thom(p)son is a unique Thom(p)son.

CONCLUSION

The data collected for this article allow us to distinguish a general trend between the personality of the Thom(p)sons, with a more withdrawn Thompson and a more extroverted Thomson. Several elements of the Tintin books infantilize the Thom(p)sons. It could suggest that they have not yet reached maturity, and still maintain a fluid and ambiguous identity. One thing is certain: Thompson and Thomson are eternal and still have plenty of time to grow up.

REFERENCES

Algoud, A. (1997) Le Dupondt sans peine. Albin Michel, Paris.

Bidaud, S. (2016) À propos des noms de personnages de Tintin. Note d’onomastique littéraire. Irish Journal of French Studies 16(1): 209–225.

Bidaud, S. (2017) Les psychopathologies dans « Les Aventures de Tintin ». Thélème 32(2): 147–157.

Bonnemain, B. (2005) Hergé et la pharmacie : Médicaments, drogues et poisons vus par Tintin. Revue d’Histoire de la Pharmacie 347(93): 475–478.

Castillo, M. (2011) Tintin and colleagues go to the doctor. American Journal of Neuroradiology 32(11): 1975–1976.

Delpérée, F. (2014) La Constitution de Tintin. Revue Française de Droit Constitutionnel 100(4): 879–886.

Groensteen, T. (2006) Le Rire de Tintin: essai sur le comique hergéen. Moulinsart, Turnhout.

Hergé. (1930). Tintin au Pays des Soviets. Casterman (2006), Tournai.

Hergé. (1931). Tintin au Congo. Casterman (2006), Tournai.

Hergé. (1932). Tintin en Amérique. Casterman (2006), Tournai.

Hergé. (1934). Les Cigares du pharaon. Casterman (2006), Tournai.

Hergé. (1936). Le Lotus bleu. Casterman (2006), Tournai.

Hergé. (1937). L’Oreille cassée. Casterman (2006), Tournai.

Hergé. (1938). L’Ile noire. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1939). Le Sceptre d’Ottokar. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1941). Le Crabe aux Pinces d’Or. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1942). L’Etoile mystérieuse. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1943). Le Secret de la Licorne. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1945). Le Trésor de Rackham le Rouge. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1948). Les 7 Boules de Cristal. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1949). Le Temple du Soleil. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1950). Tintin au Pays de l’Or noir. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1953). Objectif Lune. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1954). On a marché sur la Lune. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1956). L’Affaire Tournesol. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1958). Coke en Stock. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1960). Tintin au Tibet. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1963). Les Bijoux de la Castafiore. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1968). Vol 714 pour Sydney. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1976). Tintin et les Picaros. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Hergé. (1986). Tintin et l’Alph-Art. Casterman (2007), Tournai.

Meyer, J.-P. (2007) Étude d’un corpus particulier de perturbation langagière : Les lapsus de Dupond et Dupont dans les “Aventures de Tintin” (Hergé). In: Vaxelaire, B.; Sock, R.; Kleiber, G.; Marsac, F. (Eds.) Perturbations et Réajustements. Langue et Langage. Université Marc-Bloch, Strasbourg. Pp. 297–310.

Peeters, B. (2006) Hergé, Fils de Tintin. Flammarion, Paris.

Sadoul, N. (1989) Entretiens avec Hergé. Édition définitive. Casterman, Tournai.

Supplementary File

Translation of the present article to French.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the online Tintin fandom (tintin.fandom.com) and the Tintin Facebook group for the thorough information they provided. I am grateful to Dr. Marion Javal for her precious and relevant comments, as well as to Arnaud, Benoît, and my family for showing support in this project.

About the author

Dr Olivia Le Moëne is an ethologist and researcher in behavioural neuroscience. She is an (avid) graphic novel enthusiast and a (slight) data analysis geek. Fascinated by universes of fiction, she enjoys looking at artistic creations under the light of the scientific method.