Abraham U. Morales-Primo

Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional, Autónoma de México, Hospital General de México, Mexico City, Mexico.

Email: aump.puma (at) gmail (dot) com

Since their discovery, viruses have had a poor reputation as being synonymous with infectious diseases. These ubiquitous entities can cause illnesses ranging from mild to fatal in all living organisms. Historically, viruses have been responsible for significant public health crises, socioeconomic challenges, and environmental disruptions (Sankaran & Weiss, 2021). SARS-CoV-2, commonly known as COVID-19, has resulted in a confirmed death toll of 7.1 million as of November 2024 (WHO, 2024), triggered widespread lockdowns, and led to a global economic recession (World Bank, 2022). Interestingly, the pandemic also had temporary yet beneficial effects on the environment (Ang et al., 2023). Despite their harmful effects, viruses influence ecosystems, evolution, and even human health in ways that are not entirely detrimental (Pan et al., 2019). Viruses, for instance, regulate microbial populations, contribute to genetic diversity, and even play essential roles in modern medicine, such as gene therapy and oncolytic cancer treatments (Liu et al., 2023; Mietzsch & Agbandje-McKenna, 2017).

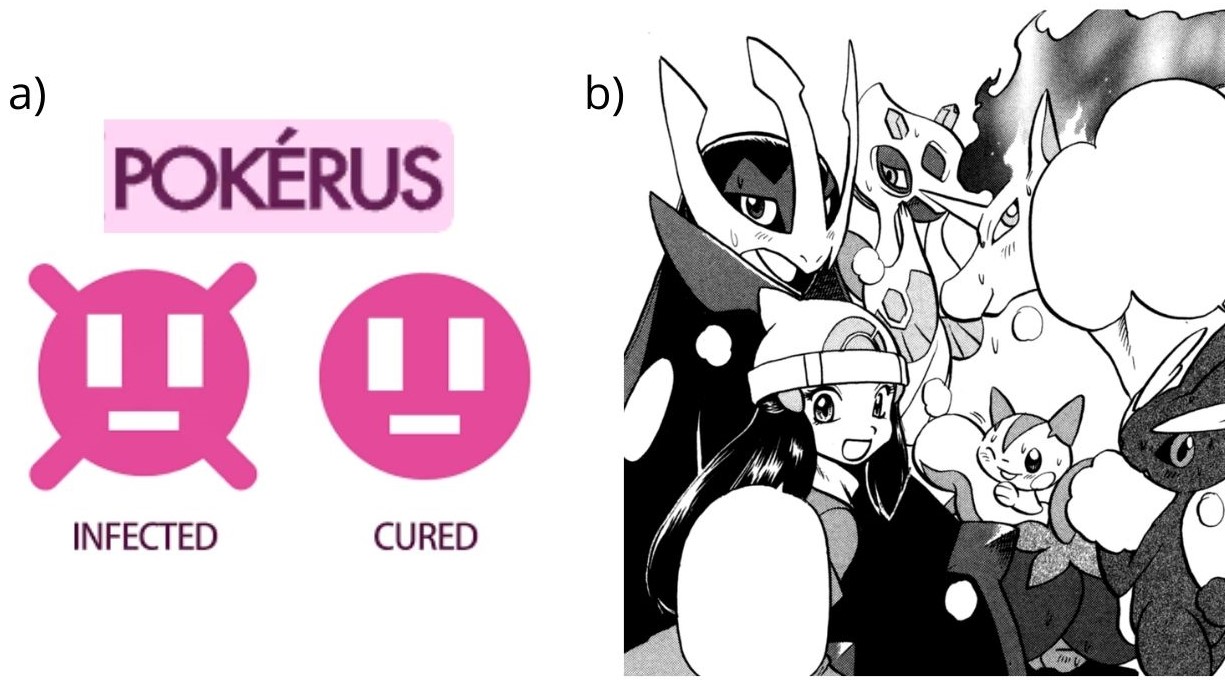

The Pokémon universe introduces a unique perspective on infectious agents through the Pokérus (PKRS), a pathogen that infects Pokémon. This world is home to a diverse array of creatures that resemble real-life animals, plants, and even inanimate objects. Pokémon are categorized based on biology into elemental types, such as Water or Grass, and abstract types like Psychic or Ghost. Regardless of their type, all Pokémon are susceptible to infection by PKRS, a multi-host virus.

Unlike most multi-host viruses, which experience fitness trade-offs due to differential gene effects across hosts, PKRS faces no such limitations (Elena et al., 2009). It is the only known infectious agent in Pokémon, with no competitors or resistant hosts. This lack of ecological constraints allows PKRS to bypass the typical evolutionary pressures that affect real-world viruses.

Remarkably, the adverse effects of PKRS are minimal compared to its benefits, as it significantly enhances Pokémon growth and development, making PKRS a mutualistic virus as well. Mutualistic viruses might show three different positive effects on a host’s fitness: protection, invasion, and, like in the case of PKRS, development (Pradeu, 2019). Viral-enhanced development is the result of co-evolution between the virus and its host (Pradeu, 2019). Viruses also enhance the host’s fitness through the activation of their immune system, whether through immunological memory or immunotherapies (Welsh et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2023). Regardless of the mechanism, PKRS biology remains a mystery; however, it offers a valuable opportunity to examine mutualistic viral interactions through a fictional lens. By comparing PKRSs with real-world immunological and evolutionary processes, we aim to explore how an infectious agent could plausibly enhance host development. In doing so, this analysis not only deepens our understanding of viral-host dynamics but also challenges the conventional view of viruses as purely pathogenic.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY OF PKRS

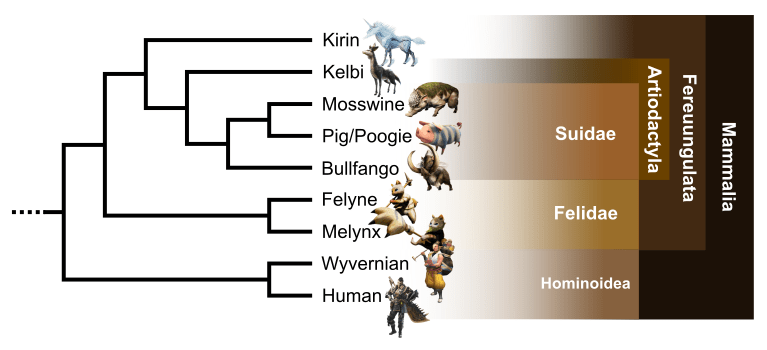

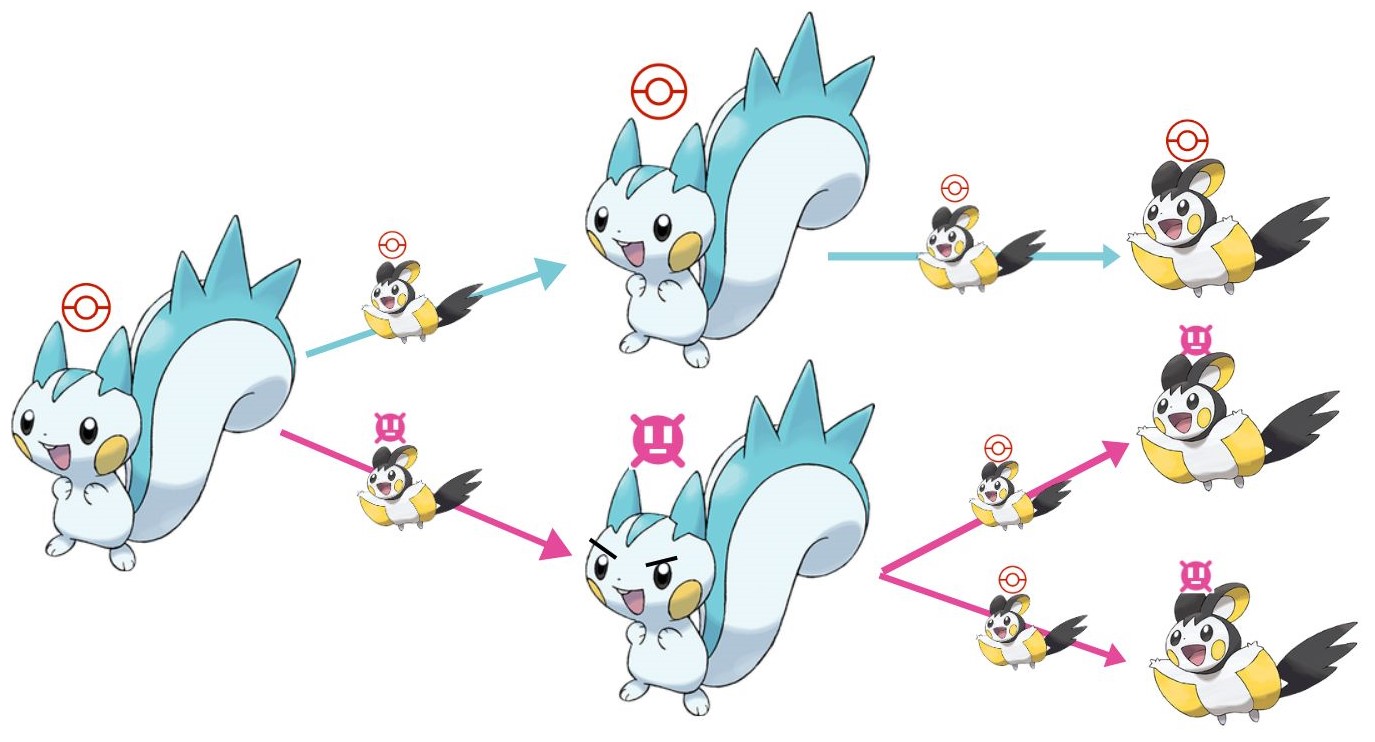

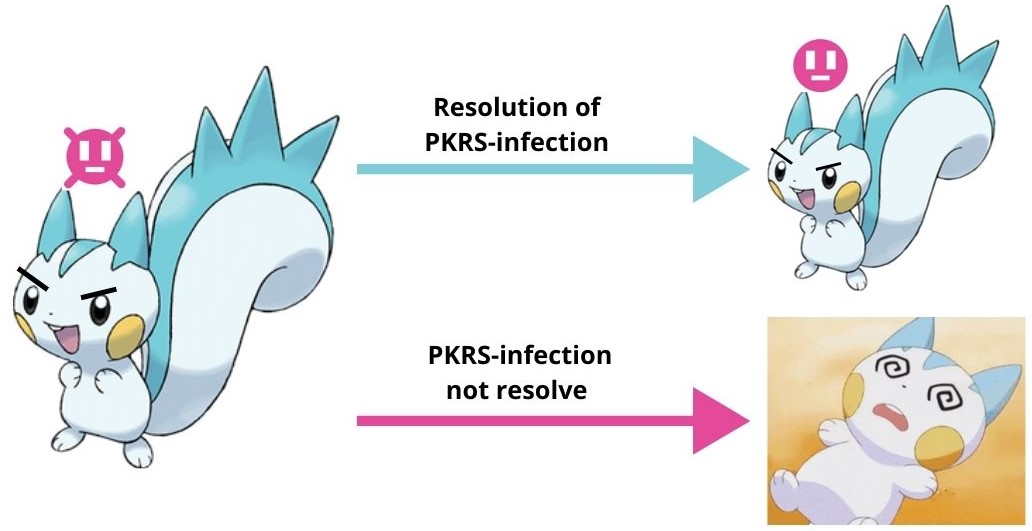

PKRS is a microscopic life-form that infects all Pokémon and spreads through direct contact between an infected and a healthy Pokémon, including eggs, within the same party. The infection lasts between one and four days, depending on the strain. Little is known about PKRS symptoms. In the video games, the infection appears asymptomatic, with affected Pokémon displaying only an icon on their info card (Fig. 1a). In the manga, however, infected Pokémon exhibit fever-like symptoms, such as sweating and facial rubor (Fig. 1b). This variability mirrors real-world infections like Influenza and COVID-19, which can range from asymptomatic cases to severe illness, though unlike these diseases, PKRS is never fatal (Shaikh et al., 2023).

Notably, PKRS resolves naturally, unaffected by external factors such as Pokémon Centers or healing items. Once cured, the Pokémon’s info card updates to reflect its non-infectious status, it can no longer spread the virus and becomes immune to it (Fig. 1a). Yet, despite being immune to reinfection, it retains the long-term benefits of having been infected. This suggests that while the active virus is eliminated, some component persists—most likely as a provirus or episome, a viral genetic sequence that remains in the host. These sequences could sustain the enhanced EV production observed after recovery. In the following section, we will explore how PKRS influences a Pokémon’s development.

POKÉMON DEVELOPMENT AND HOW IT IS AFFECTED BY PKRS

Like all living beings, Pokémon possess unique genetic-like traits set at birth that determine their individual characteristics. These traits, known as Individual Values (IVs), influence the magnitude of a Pokémon’s stats, including attack power, defensive resilience, speed, and stamina in battle. IVs range from 0 to 31, meaning that a Pikachu with 31 IVs in Attack will deal significantly more damage than a Pikachu with 0 IVs in Attack, assuming they are at the same level.

A Pokémon’s development is primarily measured in two ways: through its evolutionary progression or by its level. Unlike real-world evolutionary biology, evolution in Pokémon is not a gradual process of adaptation; instead, it involves an abrupt metamorphosis into a stronger form while retaining essential traits from its evolutionary line (Fig. 2a); however, not all Pokémon evolve, which makes level progression their main indicator of strength (Fig. 2b). A Pokémon’s level increases as it gains experience from battles, thereby improving its overall stats and combat potential. As in most role-playing video games (RPGs), defeating Pokémon grants experience, and crossing a certain threshold increases the Pokémon’s level.

Nonetheless, defeating a Pokémon grants not only experience but also Effort Values (EVs), which enhance a Pokémon’s stats beyond its IVs baseline, complementing the leveling-up process. EVs are points that function similarly to epigenetic modifications, amplifying specific attributes regardless of a Pokémon’s innate IVs. This dynamic adjustment allows trained Pokémon to surpass their untrained counterparts, even if they share identical IVs. Pokémon, however, are limited to a total of 510 EVs across all stats, with a maximum of 252 EVs allocated to any single stat. This means that a Greninja with 31 IVs and 0 EVs in Attack will deal less damage than a fully trained Greninja with 31 IVs and 252 EVs in Attack.

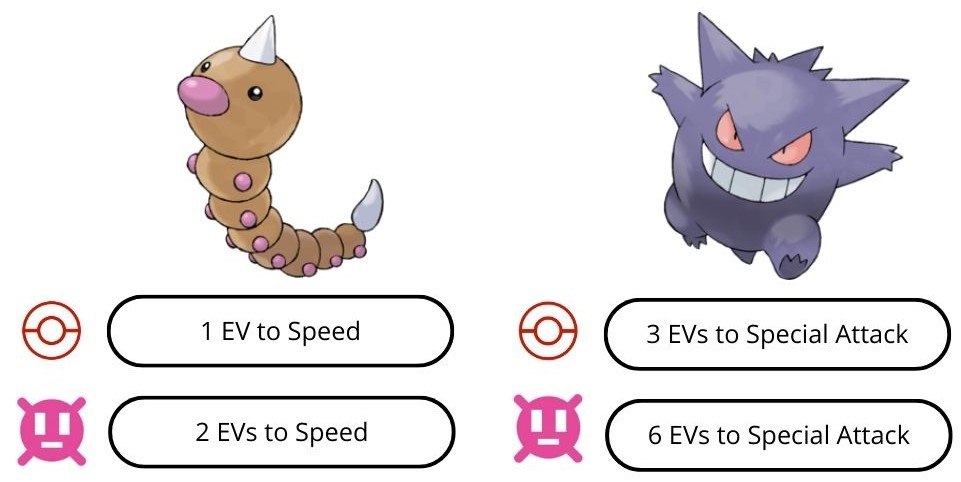

Each Pokémon, when defeated, grants a specific number of EVs to one or multiple stats, with yields ranging from one to three points. To illustrate, defeating a Weedle provides 1 EV in Speed, while a Gengar grants 3 EVs in Special Attack (Fig. 3). Understanding which Pokémon yield specific EVs is essential for optimizing a Pokémon’s training and maximizing its potential in battle.

This is where PKRS comes into play. A Pokémon infected with PKRS, or a cured one, gains twice the usual amount of EVs from defeated opponents, significantly reducing training time by half. Using the previous example, a Weedle that normally grants 1 EV in Speed will instead provide 2 EVs to an infected Pokémon, while a Gengar will yield 6 EVs in Special Attack instead of 3 (Fig. 3). For this reason, PKRS is considered a mutualistic virus that speeds up the development of a Pokémon instead of being detrimental. Yet, if PKRS is such a beneficial mutualistic virus, why is it only temporary? And if it enhances a Pokémon’s growth, what evolutionary advantage does PKRS itself gain from this interaction? These questions, and more, will be approached in the next section.

PHYSIOLOGICAL AND EVOLUTIONARY MECHANISMS OF PKRS

While the effects of PKRS are well-documented in video games, its underlying biological mechanisms remain a mystery. This raises several key questions regarding its nature and function. (1) PKRS enhances EV gain, but what exactly are EVs from a biological standpoint? (2) If the virus establishes a mutualistic relationship with Pokémon, what benefits does each party gain? (3) Furthermore, if PKRS provides such an advantage, why do Pokémon eventually eliminate it from their system? (4) Finally, what molecular and physiological mechanisms does PKRS trigger to amplify EV accumulation? By examining examples from real-world viruses, we can begin to uncover possible explanations for these intriguing dynamics.

BIOLOGICALLY, WHAT ARE EVs?

As previously discussed, EVs are acquired by defeating opposing Pokémon, and a PKRS-infected Pokémon doubles the rate at which it gains EVs. Pokémon, however, can also obtain EVs through another method that provides further insight into their nature: the consumption of vitamins. In the Pokémon world, “vitamins” refer to items that enhance a Pokémon’s stats. These include HP Up, Zinc, Iron, Carbos, Protein, and Calcium—none of which are true vitamins but rather a combination of macro and micronutrients.

This suggests that EVs are not merely absorbed from defeated Pokémon but are instead naturally produced during training. Thus, these vitamins may serve as cofactors that enhance the EV generation process. Indeed, the intake of macro and micronutrients is not only essential for overall health but also plays a crucial role in boosting physical performance (Beck et al., 2021; Ormsbee et al., 2014). Since EVs are produced during physical activity, they may share functional similarities with myokines and exerkines—molecular signals released during exercise that enhance cardiovascular, muscular, and immune health (Chow et al., 2022; Leal et al., 2018).

Moreover, micronutrients are crucial for the function of myokines and exerkines, further linking dietary intake to the heightened production of EVs. For example, decorin, a small pro-myogenic myokine, inactivates the muscle-growth inhibitor Myostatin (MSTN) in a zinc-dependent manner (Lee & Jun, 2019). Likewise, osteonectin, a calcium-binding myokine, is constitutively expressed in mineralized tissues, playing a role in bone formation, cellular processes, and regulation of metal ions and growth factors (Robey, 2008). Given these parallels, EVs may serve as developmental enhancers through physical training, a process further amplified by dietary supplementation.

WHAT DOES PKRS GAIN FROM THIS STRATEGIC SYMBIOSIS?

To fully understand the PKRS-Pokémon relationship, we must also consider the benefits PKRS gain from infecting a host. As a virus, PKRS can be considered a genetic parasite, relying on host cells to replicate and spread its genetic material (Taylor, 2014). Since PKRS is transmitted exclusively during battles, we can infer that direct contact between Pokémon is required for infection. In virology, direct transmission includes skin-to-skin contact, airborne droplets, and bloodborne pathways, among others (Taylor, 2014). Although Pokémon are occasionally depicted with injuries, bleeding is not a recognized game mechanic. Thus, it is reasonable to narrow PKRS transmission to airborne and skin contact mechanisms during the physical exchanges of battle. We can narrow it further if we consider that not all attacks make physical contact, leaving us with only airborne transmission.

Once the mode of transmission is clarified, we can return to the original question: What does PKRS gain from infecting a Pokémon? The most straightforward answer is that it replicates within the host and then transmits to another Pokémon to perpetuate its life cycle. However, a deeper question arises: What does PKRS gain from making the infected Pokémon stronger? The answer likely ties back to its ultimate goal: increasing the chances of transmitting PKRS to another host. But how does making a Pokémon stronger contribute to this process?

Considering all our conjectures, we know that PKRS accelerates the training process. Since it only remains active within a host for up to four days, we can hypothesize that an infected Pokémon becomes more inclined to battle during this window, having grown stronger in that short period. This increased battle engagement would, in turn, enhance the chances of PKRS transmission (Fig. 4). Interestingly, this idea is not without precedent in the biological world. Several viruses are known to alter their host’s behavior or have short windows of high transmissibility. For example, the rabies virus (RBVM) is a fatal neurotropic virus that causes rabies in mammals. Neurological symptoms include delirium and aggressive behavior, which often render infected individuals erratic and violent (Khairullah et al., 2023). Since rabies spreads through bites, these behavioral changes significantly increase the likelihood of viral transmission (Fisher et al., 2018). PKRS does not appear to alter a Pokémon’s behavior drastically. Still, it likely increases the Pokémon’s impetus to engage in battle, thereby enhancing the chances of spreading the virus to more opponents. On the other hand, a real-world example of a short-lived, directly transmitted virus is the severe case of the Ebola virus (EBOV). EBOV is the etiological agent of Ebola virus disease (EVD), which is characterized by significant fluid loss and internal bleeding, typically progressing over a period of 2 to 20 days, with 10 days being most common (Feldmann et al., 2020). Transmission occurs through direct contact with contaminated bodily fluids, including blood, saliva, and sweat (Vetter et al., 2016). While PKRS symptoms are far less severe, the inferred mode of transmission shares similarities. In conclusion, given that Pokémon battles involve close contact and intense exertion, we propose that PKRS is transmitted via airborne microdroplets—such as sweat or saliva—released during these interactions.

WHY DO POKÉMON OVERCOME PKRS IF IT MAKES THEM STRONGER?

If PKRS is so beneficial to Pokémon, why hasn’t it become a permanent feature of their biology—perhaps even integrated into the Pokémon’s genome over time? Processes such as endogenization could allow PKRS to integrate with the host’s DNA. A good example of this process is found in parasitoid wasps, which inject their eggs into a host along with virus-like structures produced from endogenous viral elements (EVEs) (Guinet et al., 2023). These viral elements help dampen the host’s immune system, facilitating the development of the insect (Guinet et al., 2023). A closer example can be seen in Syncytin-1, a protein that developed from endogenous retroviruses and is essential for forming the syncytiotrophoblast, a tissue that separates maternal and fetal bloodstreams in the placenta (Chuong, 2018). However, for this process of viral domestication to occur, two key factors are required: a long time span and persistent selection pressure (Holmes, 2008).

Interestingly, PKRS is absent in the Pokémon Legends: Arceus game, which is set in a distant past (approximately 200 years ago). This suggests that PKRS is a relatively recent viral emergence, not yet present in earlier Pokémon populations. As such, the necessary evolutionary time for integration or co-evolution has likely not occurred.

Another potential explanation is immunological tolerance. If PKRS were so beneficial, perhaps the immune system would allow it to persist, similar to how the gut microbiota maintains a balanced relationship with the immune system (Shao et al., 2023). However, this does not seem to be the case. Once the four-day infection period ends, the host gains immunity and becomes resistant to reinfection. This indicates the presence of immunological memory and suggests that PKRS is ultimately cleared by the host’s immune system.

So, why does this happen? One possibility is that while PKRS is beneficial in the short term, it may pose long-term risks. If an infected Pokémon is more inclined to battle, this could lead to overexertion (Fig. 5). Constant and prolonged physical exertion could result in conditions such as Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) or Exertional Rhabdomyolysis (ER) (Kreher & Schwartz, 2012). While OTS generally leads to fatigue and performance decline, ER is particularly dangerous, causing skeletal muscle damage and necrosis that can lead to multiple organ dysfunction (Yang et al., 2025). This constant strain could overwhelm the Pokémon’s body, triggering an immune response to eliminate the virus before the damage becomes irreversible.

Ultimately, the Pokémon’s immune system clears the virus, but the enhanced EV production persists, allowing the Pokémon to retain the short-term advantages of PKRS without the associated risks. In this way, PKRS might enhance the Pokémon’s battle capabilities for a limited period, but its potential for overexertion necessitates the virus being expelled before significant harm can occur.

SO, HOW DOES PKRS BOOST EV PRODUCTION?

Finally, let’s discuss the mechanisms behind the overproduction of EVs by PKRS. Since Pokémon naturally produce EVs, it’s reasonable to infer that enzymatic processes are involved. Let’s call the hypothetical enzyme responsible for this process ‘EVase’. Thus, PKRS must be influencing EVase activity in some capacity—either by increasing its production, enhancing its function, or both. Several plausible mechanisms could explain this interaction involving genetic and molecular strategies.

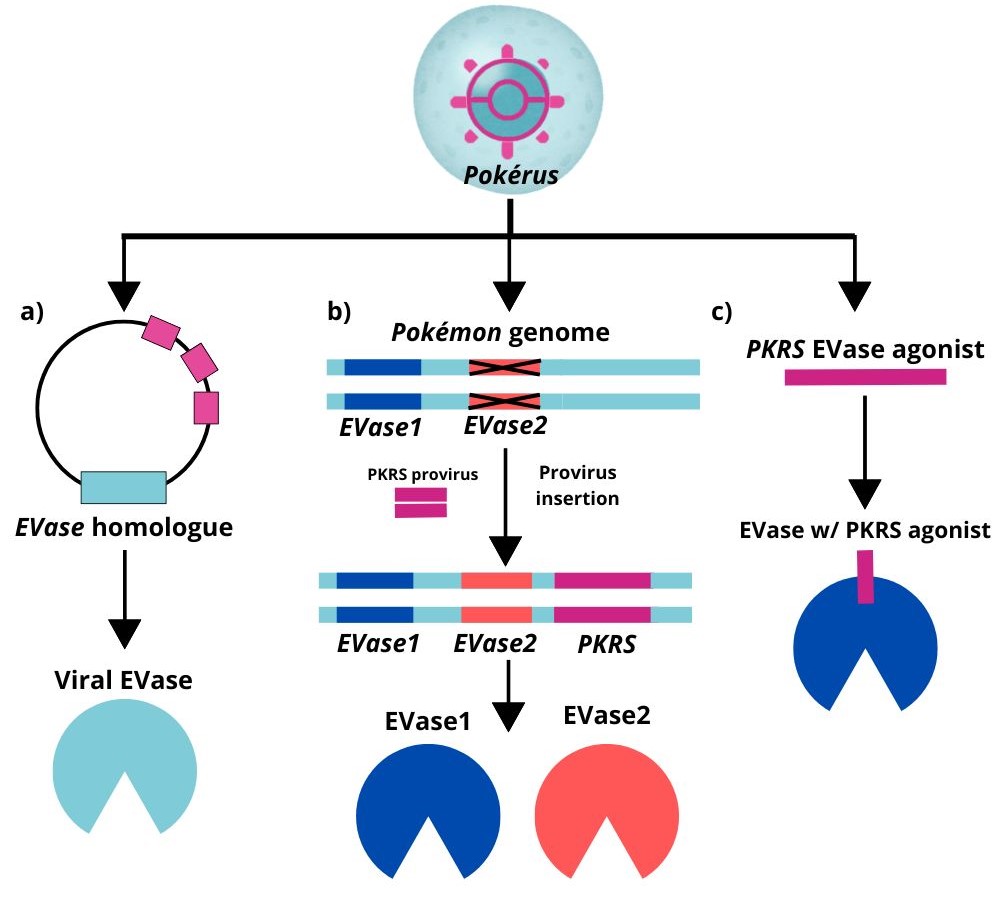

To begin with, PKRS could possess oncovirus-like traits, including gene activation, genomic instability, and the production of host-homologue proteins (Mui et al., 2017). First, PKRS might encode an EVase-like homologue, thereby enhancing EV production (Fig. 6a). A relevant example is the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which encodes latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1)—a homologue of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (Cameron et al., 2008). LMP1 mimics TNF’s function by activating intracellular pathways such as NF-κB, contributing to the virus’s oncogenic potential (Cameron et al., 2008).

A second possibility is that PKRS genome insertion activates EVase-related genes, such as secondary copies or other members of the EVase protein family (Fig. 6b). This mechanism resembles insertional mutagenesis seen in retroviruses like Murine leukemia virus (MuLV), which frequently integrates near the host proto-oncogene myc, leading to its activation and the onset of neoplasia (van Lohuizen et al., 1989).

A third and final possibility is that PKRS produces an agonist—a molecule that directly enhances the function of EVase (Figure 6c). Rather than altering gene expression, PKRS could synthesize a viral protein or RNA that binds to EVase, stabilizing it or increasing its catalytic efficiency. A compelling precedent can be found in the influenza virus, which generates aberrant mini viral RNAs (mvRNAs) that act as agonists for the host immune receptor RIG-I, triggering an antiviral response via interferon-β production (Te Velthuis et al., 2018).

Altogether, these mechanisms illustrate the diverse strategies PKRS might employ to enhance EV production, ranging from encoding viral homologues to manipulating host gene expression and enzyme activity. While each hypothesis draws from well-established viral behaviors, they remain speculative in the context of PKRS. Nonetheless, they offer a compelling framework to understand how a seemingly benign virus could permanently alter a host’s physiology for enhanced development.

CONCLUSION

PKRS is a multi-host virus capable of infecting every known Pokémon species. While it may cause mild symptoms, its overall benefits to Pokémon’s growth and development far outweigh any detrimental effects. Despite its in-game simplicity, little is known about the virus’s biology, leaving us to speculate on its physiological and evolutionary mechanisms. Notably, PKRS enhances EV production during training, though only for about four days. This limited timeframe suggests that the host immune system effectively clears the virus, subsequently establishing immunity. Its spreading strategy may involve temporarily boosting the host’s performance, thereby increasing encounters with other healthy Pokémon and facilitating transmission. Lastly, PKRS could boost EV production through molecular mechanisms such as the activation of EVase-related genes, the expression of EVase-homologue proteins, or the synthesis of EVase agonists. Understanding PKRS may not only reveal the secrets of this beneficial infection but also offer broader insights into host-virus coevolution and enhancement.

REFERENCES

Ang, L.; Hernández-Rodríguez, E.; Cyriaque, V.; Yin, X. (2023) COVID-19’s environmental impacts: Challenges and implications for the future. Science of the Total Environment 899: 165581.

Beck, K.L.; von Hurst, P.R.; O’Brien, W.J.; Badenhorst, C.E. (2021) Micronutrients and athletic performance: A review. Food and Chemical Toxicology 158: 112618.

Cameron, J.E.; Yin, Q.; Fewell, C.; et al. (2008) Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces cellular MicroRNA miR-146a, a modulator of lymphocyte signaling pathways. Journal of Virology 82: 1946–1958.

Chuong, E.B. (2018) The placenta goes viral: retroviruses control gene expression in pregnancy. PLOS Biology 16: e3000028.

Chow, L.S.; Gerszten, R.E.; Taylor, J.M.; et al. (2022) Exerkines in health, resilience and disease. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 18: 273–289.

Elena, S.F.; Agudelo-Romero, P.; Lalić, J. (2009) The evolution of viruses in multi-host fitness landscapes. The Open Virology Journal 3: 1.

Feldmann, H.; Sprecher, A.; Geisbert, T.W. (2020) Ebola. New England Journal of Medicine 382: 1832–1842.

Fisher, C.R.; Streicker, D.G.; Schnell, M.J. (2018) The spread and evolution of rabies virus: conquering new frontiers. Nature Reviews Microbiology 16: 241–255.

Guinet, B.; Lepetit, D.; Charlat, S.; et al. (2023) Endoparasitoid lifestyle promotes endogenization and domestication of dsDNA viruses. eLife 12: e85993.

Holmes, E.C. (2008) Evolutionary history and phylogeography of human viruses. Annual Review of Microbiology 62: 307–328.

Khairullah, A.R.; Kurniawan, S.C.; Hasib, A.; et al. (2023) Tracking lethal threat: in-depth review of rabies. Open Veterinary Journal 13: 1385.

Kreher, J.B. & Schwartz, J.B. (2012) Overtraining syndrome: a practical guide. Sports Health 4: 128–138.

Leal, L.G.; Lopes, M.A.; Batista, M.L. Jr. (2018) Physical exercise-induced myokines and muscle-adipose tissue crosstalk: a review of current knowledge and the implications for health and metabolic diseases. Frontiers in Physiology 9: 1307.

Lee, J.H. & Jun, H.S. (2019) Role of myokines in regulating skeletal muscle mass and function. Frontiers in Physiology 10: 42.

Lin, D.; Shen, Y.; Liang, T. (2023) Oncolytic virotherapy: basic principles, recent advances and future directions. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 8: 156.

Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, T.; et al. (2023) Viruses regulate microbial community assembly together with environmental factors in acid mine drainage. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 89: e01973.

Mietzsch, M. & Agbandje-McKenna, M. (2017) The good that viruses do. Annual Review of Virology 4: 3–5.

Mui, U.N.; Haley, C.T.; Tyring, S.K. (2017) Viral oncology: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 6: 111.

Ormsbee, M.J.; Bach, C.W.; Baur, D.A. (2014) Pre-exercise nutrition: the role of macronutrients, modified starches and supplements on metabolism and endurance performance. Nutrients 6: 1782–1808.

Pan, D.; Nolan, J.; Williams, K.H.; et al. (2017) Abundance and distribution of microbial cells and viruses in an alluvial aquifer. Frontiers in Microbiology 8: 1199.

Pradeu, T. (2016) Mutualistic viruses and the heteronomy of life. Studies in history and philosophy of science part C: studies in history and philosophy of biological and biomedical Sciences 59: 80–88.

Robey, P.G. (2008) Noncollagenous bone matrix proteins. In: Bilezikian, J.P.; Raisz, L.G.; Martin, T.G. (Eds.) Principles of Bone Biology. Ed. 3. Academic Press, Cambridge. Pp. 335–349.

Ryu, W.-S. (2016) Virus life cycle. In: Ryu, W.-S. (Ed.) Molecular Virology of Human Pathogenic Viruses. Academic Press, Cambridge. Pp. 31–45.

Sankaran, N. & Weiss, R.A. (2021) Viruses: impact on science and society. In: Bamford, D.H. & Zuckerman, M. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Virology. Ed. 4. Academic Press, Cambridge. Pp. 671–680.

Shaikh, N.; Swali, P.; Houben, R.M. (2023) Asymptomatic but infectious – the silent driver of pathogen transmission. A pragmatic review. Epidemics 44: 100704.

Shao, T.; Hsu, R.; Rafizadeh, D.L.; et al. (2023) The gut ecosystem and immune tolerance. Journal of Autoimmunity 141: 103114.

Taylor, M.W. (2014) What is a virus? In: Taylor, M.W. (Ed.) Viruses and Man: A History of Interactions. Springer Cham, Heidelberg. Pp. 23–40.

Te Velthuis, A.J.: Long, J.C.: Bauer, D.L.; et al. (2018) Mini viral RNAs act as innate immune agonists during influenza virus infection. Nature Microbiology 3: 1234–1242.

van Lohuizen, M.; Breuer, M.; Berns, A. (1989) N-myc is frequently activated by proviral insertion in MuLV-induced T cell lymphomas. The EMBO Journal 8: 133–136.

Vetter, P.; Fischer, W.A.; Schibler, M.; et al. (2016) Ebola virus shedding and transmission: review of current evidence. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 214: S177–S184.

Welsh, R.M.: Selin, L.K.; Szomolanyi-Tsuda, E. (2004) Immunological memory to viral infections. Annual Review of Immunology 22: 711–743.

WHO [World Health Organization]. (2024) COVID-19 deaths. WHO COVID-19 dashboard. Available from: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths (Date of access: 20/Apr/2025).

World Bank. (2022) World Development Report 2022: Finance for an equitable recovery. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Washington, D.C.

Yang, B.F.; Li, D.; Liu, C.L.; et al. (2025) Advances in rhabdomyolysis: A review of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Chinese Journal of Traumatology: in press.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by using Grammarly for grammar and style suggestions. The author reviewed, edited, and revised the texts and suggestions to his liking and takes ultimate responsibility for the content of this publication.

About the author

MSc. Abraham U. Morales-Primo is a Mexican biologist specializing in the role of NETs in leishmaniasis. A proud geek, he explores the immunological and evolutionary mechanisms of diseases—even in fictional universes. When he’s not theorizing about fictional viruses, he’s dreaming up new ways to blend science with video game culture—all in the company of his wife and their beloved puppy.