Rodrigo B. Salvador1 & Barbara M. Tomotani1,2

1Finnish Museum of Natural History, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

2Department of Arctic and Marine Biology, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway.

Emails: salvador.rodrigo.b (at) gmail (dot) com; babi.mt (at) gmail (dot) com

When watching, reading or playing works of fiction, we are the type of biologists who get annoyed with silly mistakes. Like when a movie has a bird sound that’s not appropriate to the region or that belongs to a different bird species than shown; common cases include the screaming piha, the loon and the bald eagle vs red-tailed hawk, which have become more of common knowledge of late (Vox, 2021; Eberwein, 2025). We understand that sometimes choices are made in detriment to real-world biology, like Robin’s robin in Honkai: Star Rail (Salvador, 2024), and that is absolutely fine. Still, it can be quite disappointing when mistakes could have been prevented with a five-second Google search, like the other Robin’s robin in Fate/Grand Order (Salvador, 2024; Salvador & Tomotani, 2024)[1] or the many issues with the recent dinosaur films (e.g., Igielman, 2022).

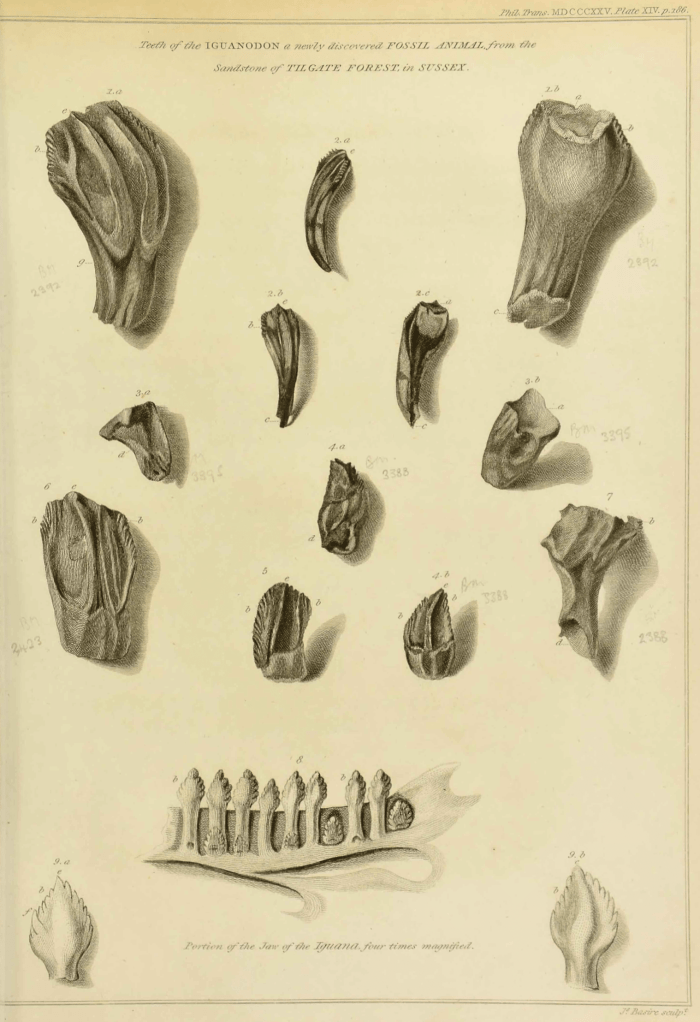

On the other hand, we cannot help but beam with happiness when creators hit a biological nail right on its head. That was the case with a dinosaur depiction in an anime we recently watched, Chapter 2 of Princess Principal: Crown Handler (by Actas, 2021). Granted, it is a very minor appearance with no relevance to the plot whatsoever, but still, there is such an interesting story behind it that we just had to write about it.

DINOS & DRAGONS

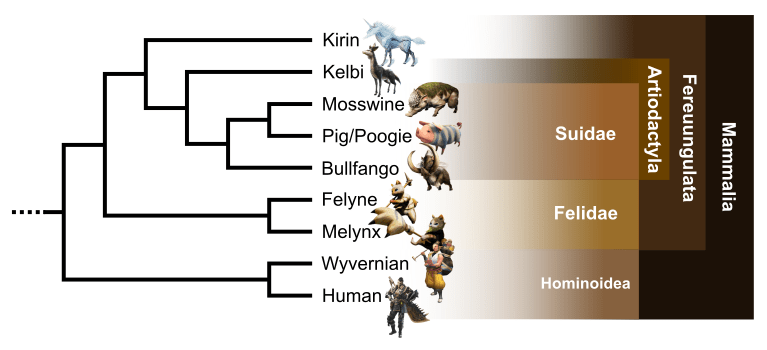

Princess Principal is set in Albion, a fictional steampunk analogue of early 20th-century Britain. The original anime series aired in 2017 and now the Crown Handler series is being released as six films (we’re currently in the 4th one). The story follows a group of five girls doing spy things; during Crown Handler Chapter 2, they go to the theatre during an investigation. And here, the small details included on this scene makes all the difference (Fig. 1).

In front of the theatre there are two lizard-like statues. Chise doesn’t know what they are, so Ange explains to her that they are extinct animals called dinosaurs. Seems straightforward enough, but there are a couple of things to unpack here. First, while the British public at that time was familiar with dinosaurs (more on that later), that was not necessarily the case elsewhere, including Japan, where Chise comes from.[2] Secondly, while the statues might look weird given our current understanding of dinosaurs, it is spot on for the period in which the anime takes place (more on that later as well). Of course, there are some nice “extra” touches, like the steam coming out of the statues’ nostrils, which is at the same time very steampunky and in line with the dragon theme of the play at the theatre.

The dinosaur depicted in the anime is Iguanodon, and its weird lizard-like appearance with a horn on its nose was just the first iteration of one of the most revised and reinterpreted dinosaurs in the history of palaeontology.

DISCOVERY AND NAMING

In the early 19th century, the British (and the European scientific community at large) were becoming acquainted with fossils of large reptilian animals, largely thanks to Mary Anning (Fig. 2), who was unearthing plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs in Lyme Regis (Fallon, 2020; Salvador, 2021). Still, some fossils were very puzzling and didn’t seem to fit well with other then known reptiles. Those included a handful of bones, teeth, and fragments that were later described as Megalosaurus (Buckland, 1824), Iguanodon (Mantell, 1825), and Hylaeosaurus (Mantell, 1833).

In 1842, the naturalist Richard Owen coined the name ‘Dinosauria’ for a new animal group that could house all those weird fossils, including carnivorous and herbivorous “reptilian” animals (Costantino, 2015).[3] That kick-started discussions and studies about such “new” animals, fuelled by more discoveries being made around the world. And Iguanodon has been in the centre of discussions ever since.

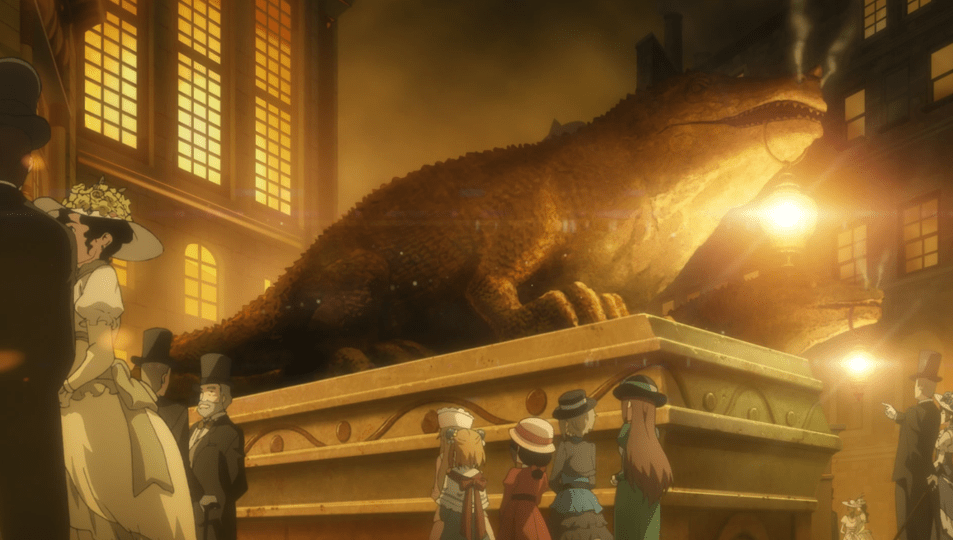

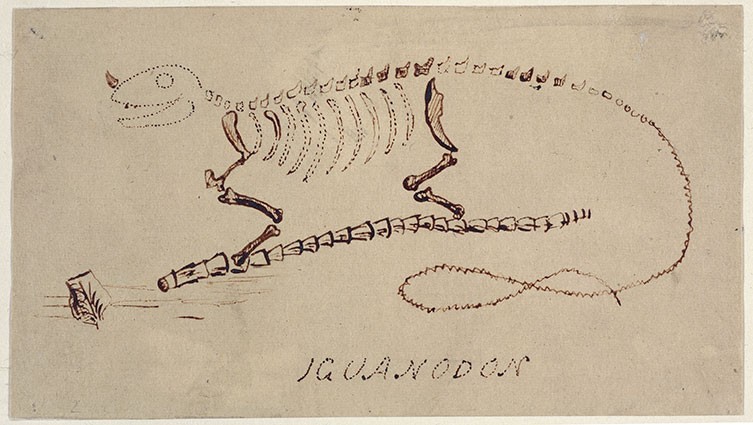

The first Iguanodon fossils came from Whitemans Green. They were rock-embedded teeth and were either found by Gideon Mantell and/or his wife Mary Ann (not Anning!) or acquired from the local quarry around 1820–1821 (Dean, 1999). At first, Mantell thought the teeth belonged to a large crocodile, but soon realized they belonged instead to a very large herbivorous reptile. That was a first, as no prehistoric reptilian herbivores were known so far (Osterloff, 2020). Among the known reptiles, the iguana had the most similar-looking teeth, although the fossils were many times larger. Thus, the new fossil species was named Iguanodon (that is, “iguana tooth”) by Mantell in 1825 (Fig. 3).[4]

In the years that followed, Mantell kept looking for more fossils, but found only more teeth and isolated and fragmentary bones (Osterloff, 2020). Then, nearly a decade later, in 1834, mine workers found a more complete specimen of Iguanodon in Maidstone.[5] Mantell travelled to Maidstone to study the new specimen, which was used as the basis for the first attempt to reconstruct this extinct animal’s skeletal structure –and also for the first artistic renderings of the species (Fig. 4). Still, the fossil was in a rather poor shape and led to some misinterpretations, the most infamous of which was the horn. Iguanodon was reconstructed as having a horn on its nose, like a rhino (remember the depiction in Crown Handler; Fig. 1). Years later, better preserved fossils showed that the “horn” was actually a modified thumb, but that was not an easy thing to imagine back in the early days of dinosaur research. Speaking of which, in a sense it was Mantell who started scientific research on dinosaurs as he tried, along a series of published papers (e.g., Mantell, 1848, 1851a), to understand Iguanodon and imagine how it lived back in the Cretaceous Period.

THE CRYSTAL PALACE

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, Mantell was clashing against Owen regarding Iguanodon. Owen was a creationist and believed that the Biblical god had created dinosaurs to be elephant-like or rhino-like creatures.[6] Mantell, however, knew that couldn’t be so, as Iguanodon had slender forelimbs and thus, should walk, move and live in a completely different manner (Mantell, 1851b; Dean, 1999). Mantell died in 1852, an event that resulted in Owen’s interpretation of Iguanodon becoming accepted and established for the following decades, in no small part thanks to the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures.

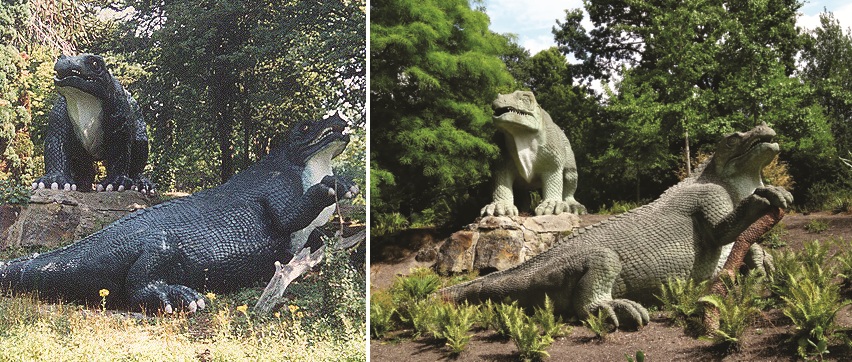

Such sculptures were commissioned in 1852 to mark the Crystal Palace’s move to its new location in London. They were made by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, who counted with scientific advice of none other than Owen (McCarthy & Gilbert, 1994). When unveiled to the public in 1854, they were the world’s first sculptures of extinct animals and should represent the latest scientific knowledge of Victorian palaeontology (Osterloff, 2023). They included species from 15 genera of extinct animals (only three of which are actual dinosaurs, by the way). Today, we know the sculptures reflect the many mistakes of early palaeontology, of which the most notable example is perhaps Owen’s interpretation of Iguanodon (Fig. 5; the wrongly positioned horn/thumb was Mantell’s fault, though). Although many people would make fun of such mistakes, that is part of how science advances and our present-day knowledge will no doubt look silly to researchers in the next century.

The sculptures are recognized as having historical importance and were restored in 2002, which attenuated the derpy look of the originals (Fig. 5). The dinosaur sculpture in Crown Handler also attenuated that derpiness by giving Iguanodon front teeth (Fig. 1), which made it (purposefully or not) look a bit more dragon-like.

IGUANODON 2.0

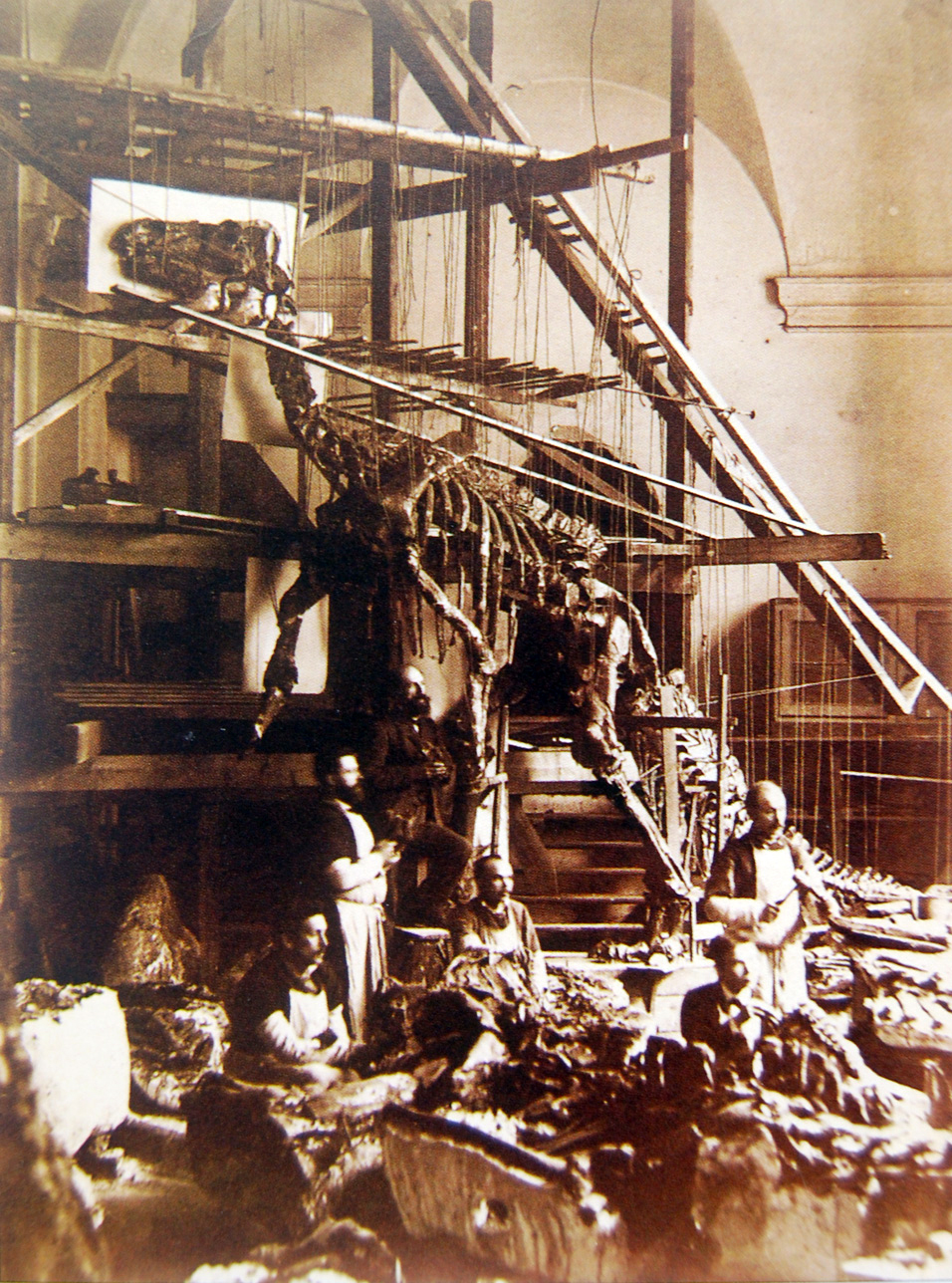

A better reconstruction of what Iguanodon would have looked like had to wait until the end of the 1870s, when nearly complete skeletons of over 30 individuals were discovered in a coal mine in Bernissart, Belgium (Norman, 1980, 2005). These belonged to a new species, Iguanodon bernissartensis. On top of the regular research on those new specimens, one skeleton was mounted for public display in Brussels by Louis Dollo (Fig. 6). With access to numerous fossils, Dollo could see that Owen’s interpretation was incorrect (Dollo, 1883). Based on what was then known about the somewhat similar Hadrosaurus in North America, Dollo mounted the Iguanodon skeleton in a bipedal kangaroo-inspired posture and hypothesized that it was amphibious and used its tail to swim (Godefrolt, 2017).

Importantly, Dollo was able to see that the “horn” was actually a modified thumb that looks like a spike (Fig. 7). To this day, palaeontologists still do not know what the hell is going on with this thumb. Some argue that it was used as a defensive weapon; others say it is a specialization for stripping leaves from branches, like the panda’s “thumb”. In any event, iguanodons’ thumbs would have been even larger in life, as the bone could have been covered with keratin (Osterloff, 2020).

After that, research on Iguanodon slowed down as interest in it waned, and wars, economic depression, and the rise of fascism changed the priorities in Europe away from dinosaurs. Then, as it is widely known, a “dinosaur renaissance” started around the 1960s, when new data and fresh research started to indicate that dinosaurs were not sluggish overgrown lizards but rather active warm-blooded animals (Bakker, 1986). Such reinterpretation started to show dinosaurs under a different light, as animals capable of complex behaviours like forming social structures and caring for their young (for instance, Maiasaura is the classic example of parental care; Horner & Makela, 1979). It took a while, but eventually, in the 1980s, the renaissance movement reached Iguanodon.

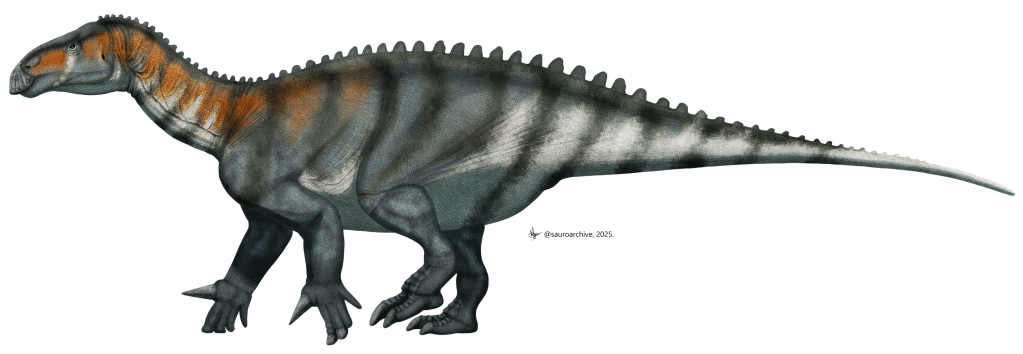

New research was done in skeletal anatomy, providing new ideas on topics like feeding mechanisms, posture and movement. Among the palaeontologists studying Iguanodon, David Norman was perhaps the most prolific and active (see, for instance, Norman, 1980, 1986). One major realization was that Dollo’s kangaroo posture was impossible, because it required a flexible tail; the fossils clearly showed that the tail of iguanodons was straight and could not bend the way Dollo displayed. Thus, the new reconstructions have iguanodons as terrestrial animals walking with their body and tail held parallel to the ground, and with arms offering further support to the body (Fig. 8). There were also discoveries about their behaviour, as rich fossiliferous deposits in Nehden, Germany, showed that iguanodons were gregarious animals (Norman, 1987).

Iguanodon was not the only one that went through reinterpretations over the decades. So, it is interesting to see how those other dinosaur reconstructions from the Crystal Palace compare to modern “post-renaissance” interpretations (Fig. 9).

Box 1. A jumble of names

In the 200 years since its original description, the genus Iguanodon had many new species added to it. Some have remained in it, like I. bernissartensis and I. galvensis (described in 2015 from Spain; Verdu et al., 2015, 2018). Many have been transferred to other genera, like I. atherfieldensis, which became Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis (Paul, 2007) and includes the Maidstone specimen formerly thought to be I. anglicus. Such reassignments were due to anatomical features observed in the fossils and differences in the geological times in which they lived (e.g., Norman, 2010, 2013) – and due the penchant of vertebrate palaeontologists for oversplitting species and naming “new” species. Case in point, many putative new species described along the years have been synonymised with other previously known species (e.g., Norman, 2013).

Curiously, many fossils identified as the original I. anglicus were shown to belong to other species; I. anglicus itself is known only by teeth and it is considered a problematic species (a nomen dubium in the jargon). That led palaeontologists Charig & Chapman (1998) to select I. bernissartensis, represented by numerous complete skeletons, as the type species of the genus Iguanodon in detriment to I. anglicus, which was the first species described.

FINAL THOUGHTS

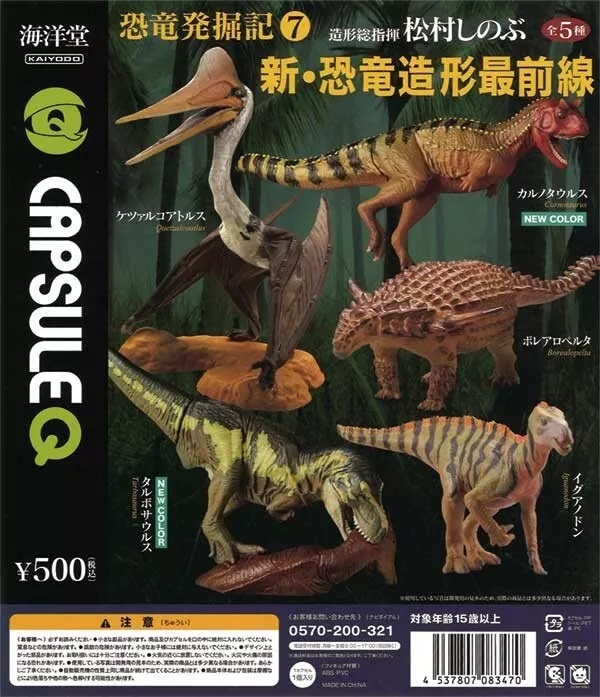

Iguanodon, while not as well immediately recognizable to the public like T-rexes, stegosaurs and triceratopses, are still rather common in pop culture from Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912) to Disney’s Dinosaur (2000) and Jurassic World Dominion (Universal Pictures, 2022). They have long been present as collectibles too, starting perhaps with the cards in German chocolate bars during the 1900s–1910s (Fig. 10) and continuing to present-day gashapon miniatures (Fig. 11).

Popular takes on iguanodons have largely followed the many changes in interpretation, from elephant-like to kangaroo-like, from terrestrial to amphibious, and finally to the modern reconstruction. While today’s iguanodons are agile bipedal animals, we cannot help but think that there is a certain charm to the fat dragon-like reconstruction of the Crystal Palace and Crown Handler. Case in point, even the King of Monsters took inspiration from the old iguanodons (Tsutsui, 2004), so we are certainly not alone in thinking that.

REFERENCES

Bakker, R.T. (1986) The Dinosaur Heresies. William Morrow, New York.

Buckland, W. (1824) Notice on the Megalosaurus, or great fossil lizard of Stonesfield. Transactions of the Geological Society of London 1: 390–396.

Charig, A.J. & Chapman, S.D. (1998) Iguanodon Mantell, 1825 (Reptilia, Ornithischia): proposed designation of Iguanodon bernissartensis Boulenger in Beneden, 1881 as the type species, and proposed designation of a lectotype. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 55: 99–104.

Costantino, G. (2015) The birth of dinosaurs: Richard Owen and Dinosauria. BHL. Available from: https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2015/10/the-birth-of-dinosaurs-richard-owen-and-dinosauria.html (Date of access: 20/Oct/2025).

Dean, D.R. (1999) Gideon Mantell and the Discovery of Dinosaurs. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Dollo, L. (1883) Note sur les restes de dinosauriens recontrés dans le Crétacé Supérieur de la Belgique. Bulletin du Musée Royal d’Histoire Naturelle de Belgique 2: 205–221.

Eberwein, E. (2025) Hollywood has been lying about what bald eagles really sound like. NENC. Available from: https://www.nenc.news/nenc/2025-07-03/bald-eagle-sound-hollywood-red-tailed-hawk (Date of access: 20/Oct/2025).

Fallon, R. (2020) Our image of dinosaurs was shaped by Victorian popularity contests. The Conversation. Available from: https://theconversation.com/our-image-of-dinosaurs-was-shaped-by-victorian-popularity-contests-130081 (Date of access: 20/Oct/2025).

Fukui Station Dinosaur Area Portal Site. (2024) Why is Fukui called the Dinosaur Kingdom? Available from: https://dinosaur-kingdom-fukui.pref.fukui.lg.jp/pages/fukui_dinosaur_en (Date of access: 20/Oct/2025).

Godefrolt, P. (2017) Les dinosaures avant Bernissart: terribles et monstrueux. Institut des Sciences naturelles. Available from: https://www.naturalsciences.be/fr/decouvrir-participer/decouvrir/les-iguanodons-avant-bernissart (Date of access: 21/Oct/2025).

Holl, F. (1829) Handbuch der Petrefactenkunde: eine Beschreibung aller bis jetzt bekannten Versteinerungen aus dem Thier- und Pflanzenreiche. Vol. 1. Ernst’schen Buchhandlung, Quedlinburg.

Horner, J.R. & Makela, R. (1979) Nest of juveniles provides evidence of family-structure among dinosaurs. Nature 282: 296–298.

Igielman, B. (2022) Jurassic World Dominion: a palaeontologist on what the film gets wrong about dinosaurs. The Conversation. Available from: https://theconversation.com/jurassic-world-dominion-a-palaeontologist-on-what-the-film-gets-wrong-about-dinosaurs-184786 (Date of access: 20/Oct/2025).

Mantell, G.A. (1825) Notice on the Iguanodon, a newly discovered fossil reptile, from the sandstone of Tilgate forest, in Sussex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 115: 179–186.

Mantell, G.A. (1833) Observations on the remains of the Iguanodon, and other fossil reptiles, of the strata of Tilgate Forest in Sussex. Proceedings of the Geological Society of London 1: 410–411.

Mantell, G.A. (1834) Discovery of the bones of the Iguanodon in a quarry of Kentish Rag (a limestone belonging to the Lower Greensand Formation) near Maidstone, Kent. Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 17: 200–201.

Mantell, G.A. (1848) On the structure of the jaws and teeth of the Iguanodon. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 138: 183–202.

Mantell, G.A. (1851a) On the structure of the jaws and teeth of the Iguanodon. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 5: 757–759.

Mantell, G.A. (1851b) Petrifications and their teachings: or, a handbook to the gallery of organic remains of the British Museum. H. G. Bohn, London.

Matsukawa, M.; Ito, M.; Nishida, N.; et al. (2006) The Cretaceous Tetori biota in Japan and its evolutionary significance for terrestrial ecosystems in Asia. Cretaceous Research 27: 199e225.

McCarthy, S. & Gilbert, M. (1994) The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs: The Story of the World’s First Prehistoric Sculptures. Crystal Palace Foundation, London.

Nagao, T. (1936) Nipponosaurus sachalinensis – a new genus and species of trachodont dinosaur from Japanese Saghalien. Journal of the Faculty of Science, Hokkaido Imperial University, Ser. 4, Geology and Mineralogy 3: 185–220.

Norman, D.B. (1980) On the ornithischian dinosaur Iguanodon bernissartensis of Bernissart (Belgium). Mémoires de l’Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique 178: 1–105.

Norman, D.B. (1986) On the anatomy of Iguanodon atherfieldensis (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda). Bulletin de l’Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique 56: 281–372.

Norman, D.B. (1987) A mass-accumulation of vertebrates from the Lower Cretaceous of Nehden (Sauerland), West Germany. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 230: 215–255.

Norman, D.B. (2005). Dinosaurs: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Norman, D.B. (2010). A taxonomy of iguanodontians (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the lower Wealden Group (Cretaceous: Valanginian) of southern England. Zootaxa 2489: 47–66.

Norman, D.B. (2013) On the taxonomy and diversity of Wealden iguanodontian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda). Revue de Paléobiologie 32: 385–404.

Osterloff, E. (2020) Iguanodon: the teeth that led to a dinosaur discovery. Natural History Museum. Available from: https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/the-discovery-of-iguanodon.html (Date of access: 21/Oct/2025).

Osterloff, E. (2023) Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and Crystal Palace Park. Natural History Museum. Available from: https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/crystal-palace-dinosaurs.html (Date of access: 21/Oct/2025).

Owen, R. (1842) Report on British fossil reptiles. Part II. Report of the Eleventh Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science [1841]: 60–204.

Paul, G.S. (2007) Turning the old into the new: a separate genus for the gracile iguanodont from the Wealden of England. In: Kenneth, C. (Ed.) Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. Pp. 69–77.

Salvador, R.B. (2019) The scientists of Assassin’s Creed. Part 1: James Cook and Charles Darwin. Journal of Geek Studies 6: 19–27.

Salvador, R.B. (2021) Mary Anning: fossil collector, paleontologist, and heroic spirit. Journal of Geek Studies 8: 19–32.

Salvador, R.B. (2024) What’s the deal with the blue “robins” in gacha games? Journal of Geek Studies 11: 69-73.

Salvador, R.B. & Tomotani, B.M. (2024) The birds of Fate/Grand Order. Journal of Geek Studies 11: 81-95.

Tsutsui, W. (2004) Godzilla on My Mind: Fifty Years of the King of Monsters. St. Martin’s Griffin, New York.

Verdú, F.J.; Royo-Torres, R.; Cobos, A.; Alcalá, L. (2015) Perinates of a new species of Iguanodon (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) from the lower Barremian of Galve (Teruel, Spain). Cretaceous Research 56: 250–264.

Verdú, F.J.; Royo-Torres, R.; Cobos, A.; Alcalá, L. (2018) New systematic and phylogenetic data about the early Barremian Iguanodon galvensis (Ornithopoda: Iguanodontoidea) from Spain. Historical Biology 30: 437–474.

Vox. (2021) Why Hollywood loves this creepy bird call. YouTube. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DVFBUIGfcJk&t=2s (Date of access: 20/Oct/2025).

About the authors

Dr Rodrigo B. Salvador is a curator in the Finnish Museum of Natural History. While his past research was mostly in palaeontology, nowadays he is mostly studying the present-day fauna. He even had a brief stint studying dinosaurs but soon left that toxic research community behind. He loves steampunk and is always on the lookout for new titles to watch, play or read. By the way, could someone give these dinosaurs top hats and monocles, please? That should improve each and every palaeoart reconstructions.

Dr Barbara M. Tomotani is a researcher in the Arctic University of Norway who has actually not seen the anime. However, she is in this article not because she has done some research on extinct dinosaurs before and neither because she studies the living fluffball dinosaur known as Parus major; no, she is here because this year she spent hundreds of hours playing Path of Titans as a Latenivenatrix, which made her go through her many old dinosaur books.

[1] Not to mention the fact that FGO writers did not know that South America and Central America are two different things, and that Mexico is located in neither of them.

[2] While current paleontological advances started to become available in Japan during the Meiji era, alongside some stories like Julio Verne’s gaining traction, the more “mainstream” dinosaur boom in Japan came in the 1980s with the amazing new discoveries that were happening in Fukui, now known as the Dinosaur Kingdom (Matsukawa et al., 2006; Fukui Station Dinosaur Area Portal Site, 2024). Technically, the first dinosaur discovered in Japan was Nipponosaurus sachalinensis, but it was found in Sakhalin (Nagao, 1936), which is now part of Russia.

[3] The name first appeared in 1841 in a talk to the British Association for the Advancement of Science. The proceedings of that meeting were published in the following year (Owen, 1842: 102).

[4] Weirdly, Mantell did not provide the full binomial that is needed for a species scientific name (like Homo sapiens). That was later coined by Holl (1829): Iguanodon anglicus.

[5] This specimen is now considered to belong to a different species in a related genus, namely Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis (Norman, 2013).

[6] Owen appears in Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate (Ubisoft, 2015) as an antagonist in a quest line where the main characters work alongside Charles Darwin. You can read a bit more about him in Salvador (2019).