Leon Corneille-Cowell

Department of Archaeology, University of York, York, UK.

Email: leoncowell96 (at) gmail (dot) com

Fantasy video games often find the player exploring and looting tombs of long-forgotten cultures and fighting otherworldly guardians. In this respect, they contain elements of archaeology albeit in an unscientific manner. The Elder Scrolls franchise is no different. This article will analyse the various burial practices in the Elder Scrolls games, finding parallels between several real-life cultures from medieval Europe to Ancient Egypt.

THE ELDER SCROLLS

The Elder Scrolls franchise has been running since 1994 and consists of eight games developed and published by Bethesda Softworks (1994–1998) and Bethesda Game Studios (2002–present). It is set in the fictional continent of Tamriel on the world of Nirn and has a rich lore and history behind it, with races and cultures adjacent to real-world cultures – a typical feature in the fantasy genre. The games follow an open-world roleplaying style in which the player character typically faces existential threats in the provinces of Tamriel, usually of divine origin from the lore’s pantheon of deities.

The Elder Scrolls are full of historical comparisons: the Nords resemble the Viking age Scandinavia, the Imperials are the Romans, and the Breton are medieval Celtic peoples. The Wood-Elves and High-Elves have been compared to indigenous North Americans/ Mongolians and Imperial China respectively, with some Tolkien influence, while the Dark Elves bear a resemblance to the Ancient Near East, and the Red Guards to medieval North Africa. The Argonions resemble Mesoamerican cultures living in jungles and the Khajit are like a variety of cultures from nomadic cultures in Eurasia and settled ones from the Indian subcontinent (Schuhart, 2021).

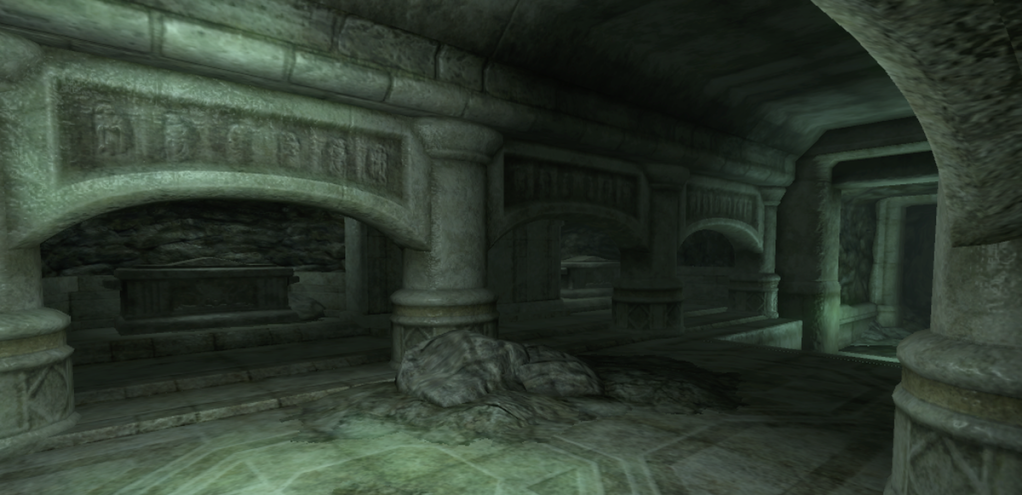

Archaeology and roleplaying games are inextricably linked – player characters will enter ancient ruins and caves to seek ancient treasures and mysteries. These often include tombs and burial grounds (Fig. 1) full of the undead and draugr. In this respect, funerary archaeology or the burial of the dead is present everywhere in the game (Parker Pearson, 2010). This article will examine the funerary and burial practices in the Elder Scrolls games and look at real-world parallels. Archaeology is not new to the franchise, with both the in-canon excavations and texts as well as projects like the Skyrim Archaeological Survey (2020).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was undertaken using the games The Elder Scrolls: Morrowind (2002), Oblivion (2006) and Skyrim (2011) as well as the associated download content (DLC) of each game. Comparison of in-game burial practices was done with real world practices using archaeological and historical literature.

DRAUGR AND DRAGON CULTS

The Draugr (Fig. 2) are undead warriors of the Nord race who most commonly inhabit Skyrim and culturally resemble early medieval Scandinavian cultures. They are followers of the dragon priests or nobility who are sealed inside tombs with them. An in-game book, Amongst the Draugr by Bernedette Bantien, which resembles a piece of anthropological/archaeological research on the Draugr observes these beings waking up daily to clean and worship the dragon priest, transferring energy to the priests to maintain their eternal afterlife (Bantien, 2012). This is a form of retainer sacrifice or the act of killing servants and burying them with their lords so they might join them in the afterlife. While human sacrifice was found in Norse burials, it is more common on a smaller scale than observed in Skyrim, and sacrifices were usually young women and often decapitated (Price, 2012: 266). Egyptian burials often contained figurines that functioned as servants for the afterlife, known as shabti (Taylor, 2001: 112). Another non-biological example of servants accompanying their overlords is the terracotta warriors of Qin Shi Huang in northern China (Man, 2007; Rawson, 2023: 348).

In the game, the dragon priests and levelled draugr bosses inhabit the main antechamber of the tombs are the remains of cult leaders or local nobility; Several of these are named and have associated quests. They are often guarding a wall covered in script resembling Norse runes, known as a ‘Word Wall’ (Williams, 2012).

In the in-game book Cadaver Preparation Findings by an Unnamed Necromancer, it is noted that the Draugr are mummified by removing certain organs that “no longer serve any function and only encumber the cadaver” and the skin is removed to prevent rot. Organ or viscera removal is a feature of Ancient Egyptian mummification; burial urns resembling Egyptian canopic jars can be found commonly in the tombs of Skyrim (Taylor, 2001: 54). The method of skin removal resembles no real-world methods of mummification; besides, Skyrim’s cold climate would have contributed to the preservation of the skin as it did with the Iron Age Scythian Pazyrk burials, in which the mummies still had their skin and even tattoos (Parker Pearson, 2010: 61; Cunliffe, 2019: 199).

Draugr are typically found laid in grouped chambers horizontally in shelving built into the wall of tombs; the monumental tombs vary in form and size. They carry corroded iron axes and swords, resembling those used by Norse warriors (Pederen, 2012). There are 44 tombs on the map in Skyrim and Solstheim, with forms resembling temples (Bleak Falls Barrow), cities (Saarthal), and barrows (Shroud Heath Barrow) (Skyrim Archaeological Survey, 2020). Norse chambered tombs have been found but many of the more prominent examples are from the Neolithic and Bronze Age (Parker Pearson, 2010; Price, 2012: 263; Cooney, 2023). The complexity of the tombs found in Skyrim is likely to be a decision based on gameplay rather than practicality, but the closest real-world examples are that of the tomb of Qin Shi Huang and those of the Ancient Egyptians (Taylor, 2001: 150; Rawson, 2023: 353).

Red Eagle

Most of the uniquely named draugr or dragon priests (quest bosses) are of Nordic descent. The one exception to this is one named ‘Red Eagle’, associated with the quest ‘The Legend of Red Eagle’ (Elder Scrolls Fandom, 2023). Red Eagle is from an ethnic group known as the Reachmen from western Skyrim, a group who has clashed with the empire and the Nords on several occasions and followed their own cultures and practices – namely, the veneration of Hargravens (witch-like creatures) and the ritual raising of Briar hearts, a form of undead. Red Eagle bears similarity to the tale of King Arthur, who fought off invaders and promised to return as well.

Overall, despite the Nord culture’s resemblances to early medieval Scandinavian and Germanic cultures. The combination of mummification, large-scale monumental tombs, and master-retainer sacrifice (notably only observed in Early Dynastic tombs), bears more in common with the burial practices of the Ancient Egyptians (Taylor, 2001).

MORROWIND ANCESTRAL TOMBS

Ancestor Tombs are found around Morrowind, usually guarded by Ancestor Ghosts or Undead. The player can access them to find loot. Ancestor worship is noted in most cultures in Tamriel but in Morrowind it is a particular point of contention between the tribunal religion of the settled towns (of whom the gods were once ancestors themselves) and the nomadic Ashlander tribes (UESPWiki, 2024a).

Ancestor worship is something that has been found in various cultures varying chronologically and geographically from the Romans to groups in Africa, the Americas and Asia (Steadman et al., 1996; Janelli & Janelli, 2000).

Falkreath Graveyard

The graveyard at Falkreath (Fig. 3) is an in-game contemporary cemetery that is still in use and maintained by Runil, the local priest of Arkay (God of the Cycle of Birth and Death) and local monk, Kust; both these NPCs reside in the Hall of the Dead (see below). It is one of two graveyards found in game, with the other being Hamvir’s Rest. When entering Falkreath for the first time, the player can witness a funeral taking place; the funeral is of a young child and consists of Runil and the two parents. It is difficult to ascertain whether this small funeral is a norm or whether it is due to the young age of the person. Archaeologically, child burials are often seen as “deviant” and to be avoided, possibly explaining the small funeral (Millett & Gowland, 2015; Evans, 2020: 58).

The graveyard bears a resemblance to medieval European cemeteries and contains many worn graves but includes those of heroes such as Hoag Merkiller thus it is considered an honour to be buried here (Elder Scrolls Fandom, 2024; Evans, 2020). Nord beliefs of the afterlife pertain that warriors travel to Sovengarde after death, an afterlife like that of the Norse Valhalla (Schodt, 2012: 220). The player can enter here in the quests ‘The World-Eater’s Eyrie’ and ‘Sovngarde’. When entering, the player can encounter several NPCs who have died in the game as well characters from the game lore and Tsun, Nord god of trials.

Hall of the Dead

Halls of the Dead are buildings encountered in most major settlements in Skyrim. These mausoleums are built for the dead to be laid to rest and be prepared to undergo funerary rites; they are usually run by a priest of Arkay. The Hall of the Dead in Whiterun and Solitude has access to the catacombs (UESPWiki, 2022). When an NPC who is associated with the settlement dies, the player can locate their body in this area afterwards.

The burial rites and treatment of the (in-game) contemporary Nordic dead vary across Skyrim from shared tombs such as in Whiterun/Solitude to inhumations such as those in Falkreath Cemetery. The reason for this difference is unclear and never explained in the game but we can hypothesise it being due to reasons such as lack of space or unsuitable geography for burials in these locations. However, Whiterun is located on vast grasslands, so this reason is improbable. It may be a cultural reason with some parts of Skyrim having more Imperial influence than others.

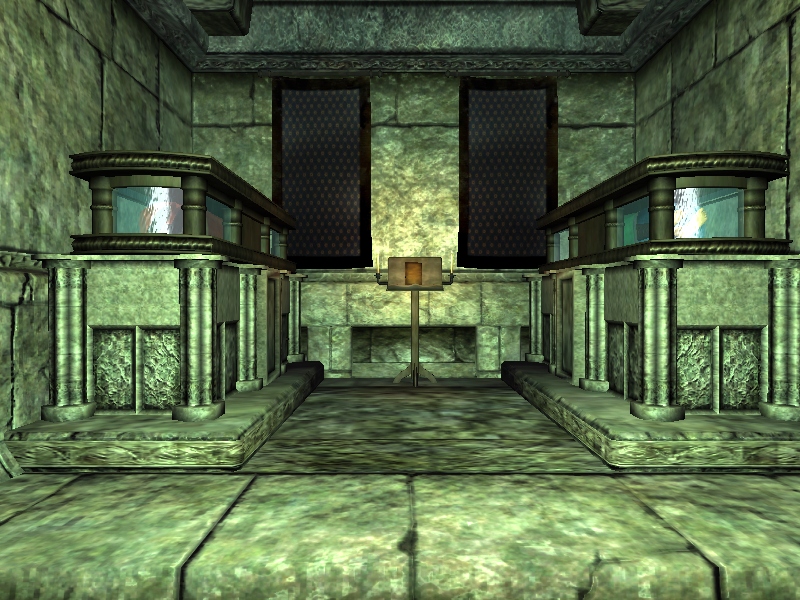

Tombs of Emperors and Holy Knights

In The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, the player undertakes a quest ‘Blood of the Divines’, to find the sacred armour of the Tiber Septim in Sancre Tor (Golden Hill) (UESPWiki, 2024c). The site has a long relationship with the imperial civilisation, dating back to the founding of the first empire by St Alessia. The site was eventually abandoned by Tiber Septim, founder of the third empire and contains the tombs of Reman (second Empire) emperors (in-game book The Legendary Sancre Tor). The tombs, of which there are five, belong to Reman I, Reman II and Reman III, plus two unmarked tombs (Fig. 4). The tombs are inscribed as such (UESPWiki, 2021):

Reman — “Here lies Reman of Cyrodiil. He defeated the Akaviri Horde and brought peace to Tamriel. 2762.“

Reman II — “Here lies Reman II of Cyrodiil, crowned Emperor of Tamriel in the year 2812. He fell in battle against the Dark Elves, in the fifty-seventh year of his age, after a reign of thirty-nine years and eight months wanting a day.“

Reman III — “Here lies Reman III, last Emperor of the Cyrodiils, the scourge of the Dark Elves, who was cruelly slain by treachery, in the year 2920. He reigned forty-three years.“

Sarcophagi like this appeared in the early Christian Byzantine transition and were typically reserved for the imperial family or martyrs (Chalkia, 2015: 57).

This matches with the next set of Sarcophagi found from the Knights of the Nine DLC (2006). The knights they contain are part of the eponymous Knights of the Nine, an order dedicated to gathering the relics of the crusader, a set of armour worn by Pelinal Whitestrake, a legendary warrior with parallels to Achilles. The knights themselves bear a resemblance to the real-life holy orders the Templars combined with elements of the Arthurian knights of the Round Table (Jones, 2018). Templar burials have been found in England in 2021 (Holder, 2021). The tombs here are effigy tombs, a common occurrence during the high/later medieval period (1000–1500 CE). Effigy tombs are monuments to the elite dead, depicting the deceased in a supine position holding an object or artefact; in this case a sword (Orme, 2021: 348; Williams, 2014). It is unclear who made the tombs, but it was likely they were commissioned by Sir Amiel Lannus, the last surviving member of the order.

NECROMANCY

It is impossible to discuss death in a fantasy setting without mentioning necromancy. Necromancy is defined as the practice of communicating with the dead to foresee the future or, more generally, black magic (Cambridge Dictionary, 2024). This practice dates to antiquity and has been found in Ancient Egypt, Babylonia, Greece, Rome, and China. In Ancient Greece, people would travel to the Neckromanteion, where they took part in complex rituals involving psychological and physical preparation including a specialised diet (broad beans, milk, oysters, honey, pork, barely bread), as well as chanting and rituals; then the people entering a soundless room where a figurine was manipulated with pulleys and levers to speak to them (Aggaili, 2015: 31). There are also accounts of it dating from the medieval and renaissance eras and relying on plants from the nightshade family to create hallucinogenic affects. In the contemporary world, the use of Ouija boards and séances continues the practice.

In modern fantasy, necromancy concerns the raising of dead thralls using black magic and achieving immortality through lichdom. Immortality has famously been sought by philosophers and emperors such as Qin Shi Huang (Man, 2007). In The Elder Scrolls, in-game attitudes to necromancy vary from province to province, with some areas being accommodating while others treat it as a taboo. The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion depicts necromancy as taboo and involves a quest whereupon the player faces the king of the necromancers Mannimarco during the Mages Guild questline (UESPWiki, 2023a). The player is unable to use necromancy without obtaining a special item, the Staff of Worms. In Skyrim, necromancy can be used by the player as part of the conjuration magic school, though there are several quests and encounters in which necromancers are villains (UESPWiki, 2023b). In the real world, there is archaeological evidence of preventing the dead from resurrecting; for instance, the practice of mutilating corpses to stop them from rising as revenants has been noted in a possible case study in the deserted medieval village of Wharram Percy in England (Mays et al., 2017).

City of the Dead

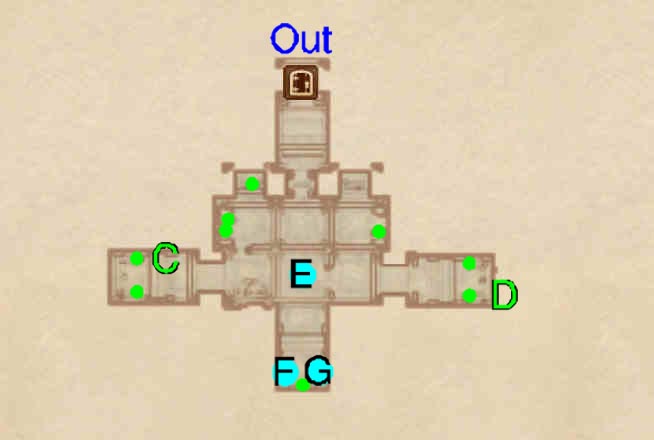

During the Shivering Isles DLC, the player can encounter the ruined city of Vitharn. The ruin is inhabited by the ghosts of its past inhabitants being attacked by ghosts of a tribe of Fanatics (in-game book Fall of Vitharn by an Unknown Author). These are cursed by the island’s mad god Daedra. The main zones of the city are its Keep, Bailey, Mausoleum, Sump and Reservoir (UESPWiki, 2024b). In the centre of the Mausoleum sits a brazier (marked by an ‘E’ in Fig. 6). In the Mausoleum’s western wing, there are the coffins for Countess Sheen-In-Glade and Count Csaran Vitharn, separated by a glass display with jewellery (Fig. 6: C). The eastern wing contains coffins for Countess Jideen and Count Cesrien Vitharn, with a bit more jewellery (Fig. 6: D).

The richness of the tombs (Fig. 7) and the jewellery found is indicative of the noble birth of the deceased within. The style of the coffins bears similarity to the imperial tombs of the Reman emperors mentioned before. The two possible explanations of this may be due to meta reasons related to game design or it could be postulated that the rulers of Vitharn saw themselves as equal to or higher than the god ruler of the Shivering Isles, Sheogorath. In world history, many emperors were thought to be divine, and this may have explained this similarity with the count’s attempt at usurpation and hubris (Lieven, 2022).

Mammoth Graveyards

In Skyrim, players can encounter roving bands of giants herding mammoths. Giants are tall humanoids who stand between 11 and 12 feet tall. They are not a playable race but are encountered by the player in the plains of White Run (UESPWiki, 2024d). The player can encounter the Camp of Secunda’s Kiss, located southwest of Whiterun in which several Mammoth skulls can be found with carvings on them, and it is mentioned in-game as being a place where rituals take place. It can be seen in random encounters that giants will mourn the death of mammoths, which is indicative of complex cosmological beliefs held by giants concerning their mammoths (Varnson, 2021). This suggests that giants saw mammoths as more than just livestock but held them in high regard. Archaeological studies of animal burials have found them to be part of mourning as well as ritualistic purposes (Morris, 2016).

CONCLUSION

This article has covered the wide range of burial practices shown in the games Morrowind, Oblivion and Skyrim. We have analysed them anthropologically and archaeologically and found various real-world comparisons with surprising results, such as the dragon cult burials resembling those of the Ancient Egyptians rather than those of the Norse, on which their culture is based. For the most part, the other burial types analysed resemble the real-world cultural parallels they were intended to, albeit with a fantastical twist. The practice of necromancy likewise bears little resemblance to the real-world practice of communicating with the deceased, instead focusing on the raising of undead minions and the search for immortality. This article has not discussed the MMORPG The Elder Scrolls Online (2014), however, which would provide a whole new dataset of burial practices. If one were to look at other games too, an entire volume could be written on burial practices in fantasy video games, as the interactive nature of the role-playing genre naturally lends itself to anthropological analysis.

REFERENCES

Aggaili, A. (2015) The archaeological site of Neckromanteion. In: Aggaili, A. (Ed.) The Archaeological Sites of Neckromnateion. Ministry of Culture and Sports, Athens. Pp. 20–32.

Cambridge Dictionary. (2024) Necromancy. Available from: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/necromancy (Date of access: 17/Mar/2024).

Chalkia, E. (2015) Basilica D of Nicopolis. Ministry of Culture and Sports, Athens.

Conte, M. & Kim, J. (2016) An economy of human sacrifice: the practice of sunjang in an ancient state of Korea. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 44: 14–30.

Cunliffe, B. (2019) Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Elder Scrolls Fandom. (2023) Red Eagle. Available from: https://elderscrolls.fandom.com/wiki/Red_Eagle (Date of access: 14/Feb/2024).

Elder Scrolls Fandom. (2024) Falkreath Graveyard. Available from: https://elderscrolls.fandom.com/wiki/Falkreath_Graveyard (Date of access: 17/Feb/2024).

Evans, L. (2020) Burying the Dead: An Archaeological History of Burial Grounds, Graveyards and Cemeteries. Pen & Sword History, Yorkshire.

Holder, B. (2021) Forgotten Graves of the Knights Templar Rediscovered in Village Churchyard. Stourbridge News. Available from: https://www.stourbridgenews.co.uk/news/19710449.historic-graves-knights-templar-discovered-enville/ (Date of access: 28/Feb/2024).

Janelli, R.L. & Janelli, D.Y. (2000) Ancestor Worship and Korean Society. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Jones, D. (2018) The Templars: The Rise and Spectacular Fall of God’s Holy Warriors. Penguin Books, New York.

Man, J. (2007) The Terracotta Army. Bantam Press, London.

Mays, S.; Fryer, R.; Pike, A.W.G.; Cooper, M.J.; Marshall, P. (2017) A multidisciplinary study of a burnt and mutilated assemblage of human remains from a deserted Mediaeval village in England. Journal of Archaeological Science 16: 441–455.

Millett, M. & Gowland, R. (2015) Infant and child burial rites in Roman Britain: a study from East Yorkshire. Britannia 46: 171–189.

Morris, J. (2016) Mourning the Sacrifice. Behaviour and meaning behind animal burials. In: DeMello, M. (Ed.) Mourning Animals: Rituals and Practices Surrounding Animal Death. The Animal Turn. Michigan State University Press, East Lansing. Pp. 11-20.

Orme, N. (2021) Going to Church in Medieval England. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Parker Pearson, M. (2010) The Archaeology of Death and Burial. The History Press, Stroud.

Pederen, A. (2012) Viking Weaponry. In: Brink, S. & Price, N. (Eds.) The Viking World. Routledge, Oxon. Pp. 204–211.

Price, N. (2012) Dying and the dead: Viking Age mortuary behaviour. In: Brink, S. & Price, N. (Eds.) The Viking World. Routledge, London. Pp. 257–271.

Rawson, J. (2023) Life and Afterlife in Ancient China. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Schodt, J.P. (2012) The Old Norse Gods. In: Brink, S. & Price, N. (Eds.) The Viking World. Routledge, Oxon. Pp. 219–222.

Schuhart, J. (2021) Which real-world cultures inspired the Elder Scrolls’ fictional races. ScreenRant. Available from: https://screenrant.com/elder-scrolls-races-real-world-cultural-inspirations-fictional (Date of access: 17/Mar/2024).

Skyrim Archaeological Survey. (2020) The Skyrim Archaeological Survey. Available from: https://skyrimarchaeologicalsurvey.wordpress.com/ (Date of access: 13/Feb/2024).

Steadman, L.B.; Palmer, C.T.; Tilley, C.F. (1996) The Universality of Ancestor Worship. Ethnology 35(1): 63–76.

Taylor, J.H. (2001) Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

UESPWiki. (2021) Oblivion: Sancre Tor. The Unofficial Elder Scrolls Pages. Available from: https://en.uesp.net/w/index.php?title=Oblivion:Sancre_Tor&oldid=2438946 (Date of access: 17/Mar/2024).

UESPWiki. (2022) Skyrim: Hall of the Dead (Whiterun). The Unofficial Elder Scrolls Pages. Available from: https://en.uesp.net/w/index.php?title=Skyrim:Hall_of_the_Dead_(Whiterun)&oldid=2695608 (Date of access: 26/Feb/2024).

UESPWiki. (2023a) Lore: Mannimarco. The Unofficial Elder Scrolls Pages. Available from: https://en.uesp.net/wiki/Lore:Mannimarco (Date of access: 16/Feb/2024).

UESPWiki. (2023b) Skyrim: Conjuration. The Unofficial Elder Scrolls Pages. Available from: https://en.uesp.net/wiki/Skyrim:Conjuration#Necromancy (Date of access: 16/Feb/2024).

UESPWiki. (2024a) Lore: Ancestor Worship. The Unofficial Elder Scrolls Pages. Available from: https://en.uesp.net/w/index.php?title=Lore:Ancestor_Worship&oldid=2925916 (Date of access: 16/Feb/2024).

UESPWiki. (2024b) Shivering: Vitharn. The Unofficial Elder Scrolls Pages. Available from: https://en.uesp.net/wiki/Shivering:Vitharn (Date of access: 06/Mar/2024).

UESPWiki. (2024c) Oblivion: Sancre Tor. The Unofficial Elder Scrolls Pages. Available from: https://en.uesp.net/w/index.php?title=Oblivion:Sancre_Tor&oldid=2438946 (Date of access: 28/Feb/2024).

UESPWiki. (2024d) Lore: Giant. The Unofficial Elder Scrolls Pages. Available from: https://en.uesp.net/w/index.php?title=Lore:Giant&oldid=2949081 (Date of access: 17/Mar/2024).

Williams, H. (2012) Runes. In: Brink, S. Price, N. (Eds.) The Viking World. Routledge, Oxon. Pp. 281–291.

Williams, H. (2014) Speaking with Effigy Tombs. ARCHAEOdeath. Available at: https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2014/07/30/speaking-with-effigy-tombs/ (Date of access: 17/Mar/2024).

Varnson, F. (2021) Skyrim’s mournful giant reveals they aren’t just monsters. ScreenRant. Available from: https://screenrant.com/skyrim-giants-smart-race-culture-lore-elder-scrolls/ (Date of access: 17/Mar/2024).

About the author

Leon Corneille-Cowell is finishing his BSc in Archaeology and starting an Msc in Funerary Archaeology in September. His academic interest are in death, burial, osteology, and paleopathology. Since he was young, he loved fantasy and fantasy video games such as The Elder Scrolls.

One response to “Death, burial, and commemoration in The Elder Scrolls”

[…] 详情参考 […]

LikeLike