Christopher Sevin

Independent scientific educator, France.

Email: c-sevin (at) live (dot) fr

Monster Hunter is a fantasy-themed video game franchise created by the Japanese company Capcom in 2004, with the first game Monster Hunter. The player embodies, in the third person, a hunter who accomplishes quests, assigned by an organization called the Guild, by killing or capturing creatures. Since then, twenty-seven other games have taken shape, developing the lore. Each game provides its new set of ecosystems, with items, maps, flora, and bestiary.

The world of Monster Hunter, although a fantasy universe, presents a scientific dimension. The games explore the concept of trophic chain, with prey, predator, and apex predator monsters. These creatures live in many different and complex ecosystems, from volcanic areas to desert plains, through tundra, tropical forests and grassy plains, each possessing its own climate, vegetation, and geology.

A form of taxonomy is also present in-game. Some monsters have subspecies generally defined by alternate skins and, sometimes, abilities. Monsters are also grouped in families, a superior clade based in the general overall aspect of creatures. Sometimes, evolutionary explanations are given to explain links between some of these taxa, like trophic partitioning, host-parasite coevolution, or allopatric speciation. All these arguments lead us to see the bestiary of this universe as a group of taxa, linked to one another by an evolutionary history.

Two books, Hunter’s Encyclopedia 4 (2015) and Monster Hunter Rise, Official Setting Document Collection – Rampage Disaster’s Secrets (2021) present a classification tree called “Ecological Tree Plots”. However, this tree doesn’t rely on a scientific approach. Phylogeny of Monster Hunter creatures is also a recurrent topic in the fan community, with many posts on Reddit, Discord and Steam, for example. These fan-made attempts rely more on an overall morphological similarity comparison and are not based on any scientific protocol.

This article is an attempt to reconstruct a speculative phylogenetic tree by using Cladistics, observing the external anatomy of monsters. The topology of the tree will be discussed in this article. The bestiary of Monster Hunter lore contains hundreds of species presented as huntable creatures, but also items coming from fishing, insect harvesting and farming. However, cladistic is inappropriate for such a sizeable of data set (Darlu & Tassy, 1993). Thus, I only studied taxa from the first generation of Monster Hunter games, which are Monster Hunter (2004), Monster Hunter G (2005), and Monster Hunter Freedom (2005).

METHODOLOGY

To determine links between taxa and imagine a plausible evolutionary story, we decided to use the cladistic approach. By observing morphological characteristics shared by studied species, this classification method allows the creation of relative taxa groups with their hypothetical common ancestor, called clades, based on shared characters (synapomorphies). Created in the beginning of the 20th century, this methodology became popular with the work of Willi Hennig after the Second World War.

Thirty-nine taxa were morphologically analyzed. Twenty-four of them are huntable monsters. We also analyzed seven fishes obtained in-game by fishing: Burst arowana, Bomb arowana, Golden fish, Sushifish, Shringnight carp, Speartuna and Knife Mackerel. As they are very inspired by real-life counterparts (arowana, carp, tuna and mackerel), I used this close inspiration to describe internal anatomic characteristics invisible in game to the naked eye. A similar reasoning was applied to humans and pigs, present in the game and in the real world. Three insect-like creatures, Godbug, Flashbug and Thunderbug, were studied and came from collecting actions. To conclude, we incorporate wyverians, a humanoid lifeform, into the data set.

In total, eighty-five characters were studied, concerning morphology, physiology and reproduction. Character states were polarized using their repartition on the Earth (i.e. real-world) evolutionary tree; states were unordered. The character matrix was built on Nexus Data Editor (v.0.5.0; Page, 1998) and the heuristic search of the most parsimonious trees was made on PAUP (v.4.0; Swofford, 2003). To root the strict consensus tree, I decide to create two hypothetical outgroups. To test the robustness of the consensus tree, the Bremer support was calculated. The matrix used in the analysis is available as a Supplementary File to this article [1].

RESULTS

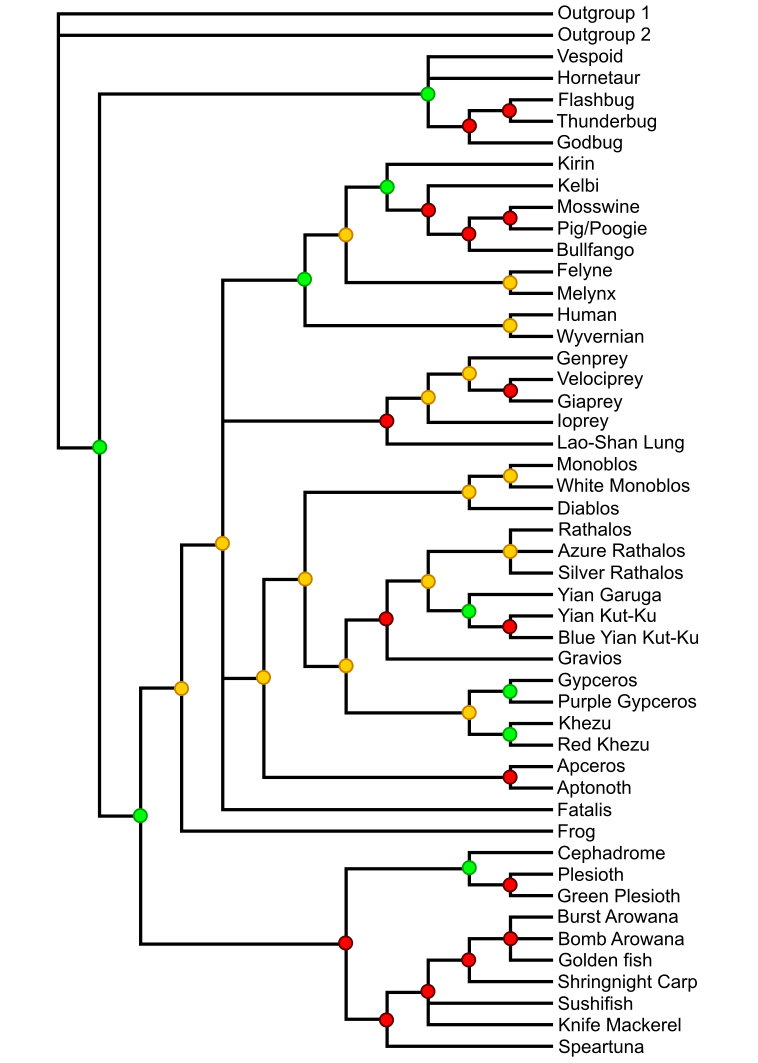

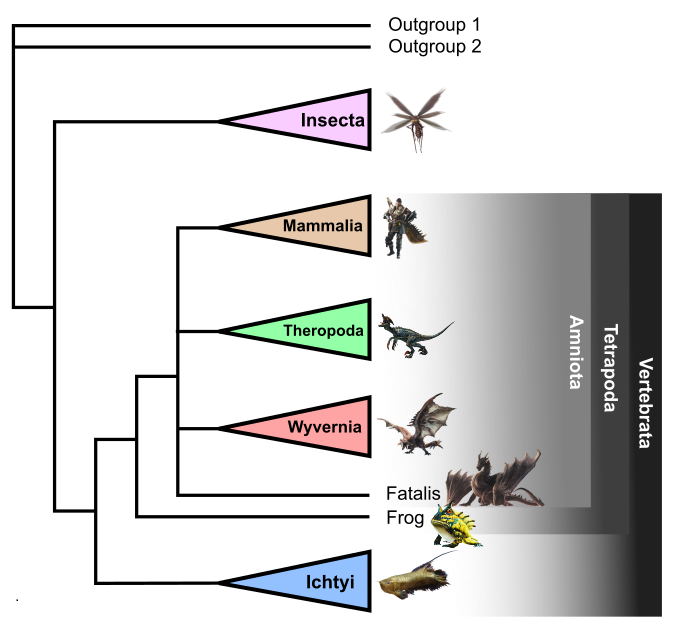

The heuristic search calculated 214,958 trees. Among them, 12 trees are the most parsimonious with a length of 165. A strict parsimonious tree was calculated, with a length of 167 steps (Fig. 1). The Consistency index (CI) is 0.623, the Rescaled consistency index (RC) is 0.556, and the Retention index (RI) is 0.899. These indexes, greater than 0.5 but close to is (except for the Retention index) indicate some cases of convergence in the consensus tree. The Bremer support was calculated to check the robustness of nodes: 16 nodes have a value of 1 and are considered weak, unsupported by a lot of character states. These weak nodes are mostly situated in the ichtyan and the insectoid clades. Among the other nodes, 15 have a value of 2 and 9 have a value of 3 or more, considered strong and supported by several character states.

DISCUSSION

The topology of the consensus tree (Fig. 1) shows some similarities with the real-world tree of life, as expected given the real-life inspiration of the monsters. A first division is made between “invertebrates”, represented by insectoid lifeforms, and “vertebrates”. The latter represent the major part of the dataset. Inside this clade, we observe a dichotomy with an ichtyan clade formed by fishes and “fish wyverns” called piscine wyvern in the Monster Hunter franchise. All fish taxa are the sister group of a tetrapod taxon (i.e. creatures with four limbs). Two other characters resulting from terrestrialization, the lacrimal canal and the atlas vertebra, are visible on real-world frog, human and pig. In the continuation of the article, I will present the details of each clade.

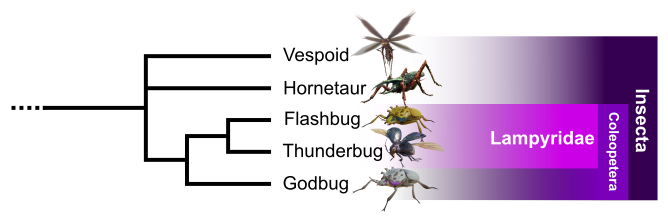

Insecta clade

A first basal group appears in the consensus tree. This clade groups Vespoid, Hornetaur, Flashbug, Thunderbug and Godbug (Fig. 2). All possess a chitinous exoskeleton, a pair of antennas, ribbed wings and six legs. These characters are similar to Earth’s insects and more precisely to the subclass Pterygota (Misof et al., 2014).

Vespoid has a social behavior evoking hymenopterans. Hornetaur, by having strong jumping legs and wings overlapping the abdomen at rest, looks like orthopterans such as locusts, grasshoppers, and crickets. Flashbug, Thunderbug and Godbug formed by the occurrence of moniliform antennas and the presence of elytra, modified hardened forewings distinctive of the order Coleoptera. To conclude, Flashbug and Thunderbug also share a bioluminescent abdomen, similar to real-life fireflies from the lampyrid family.

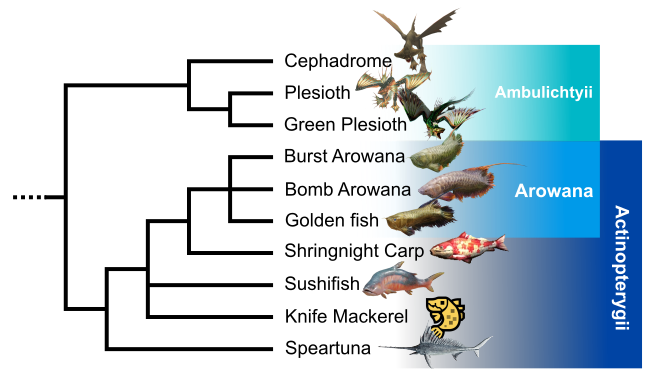

“Ichtyan” clade

Within the large vertebrate group, we observe a first clade formed by Speartuna, Knife Mackerel, Shringnight carp, the family of the Arowana (Burst arrowana, Bomb arowana and Golden fish), Cephadrome, and the two species of Plesioth (Fig. 3). These taxa share a lateral line, scale-covered skin, and fins formed by lepidotrichs. They also have opercula to protect their gills.

This clade is divided into two subunits. The first one groups Speartuna, Knife Mackerel, Shringnight carp and the family the Arowana species. All of them are closely based on real animals. They all possess ray fins, a characteristic of the real-world actinopterygian clade. The occurrence of premaxillary mobility allows us to refine the comparison with the Teleostei (Betancur-R et al., 2013).

In opposition, Cephalodrome, Plesioth and Green Plesioth form a group that I call Ambulichtyii (“walking fishes”). They present lobe fins, pelvic fins transformed and erected in back legs similar structures, a prograd biped posture and terrestrial locomotion, hence their name. This capacity to live out of the water during long periods can evoke mudskipper fish from the genus Periophthalmus (Steppand et al., 2022). It also represents, in the case of Cephalodrome who live constantly on land, a second episode of terrestrialization in in-game vertebrates. Plesioth species and Cephalodrome also have a pressurized pocket inside their body, allowing them to produce sand projectiles (Cephalodrome) and a water beam (Plesioth species). The head is fixed to the body by a neck and doesn’t show visible nostrils, suggesting a partial or complete loss of olfaction. Finally, these three taxa possess neurotoxin glands in their fins, allowing them to defend against predators.

An important point to develop in light of this consensus tree is the position of fishes and tetrapod-like creatures. Contrary to Earth, where tetrapods are contained inside lobe-finned fishes (which together are the sister group of ray-finned fishes), the Monster Hunter consensus tree presents a different topology (Fig. 1). This evolutionary tree suggests tetrapods outside the lobe-finned fishes. This result can be explained by the lack of sarcopterygian fishes (e.g., lungfishes and coelacanths) in the game, as well as the lake of basal tetrapodomorphs (e.g., Panderichtys, Tiktaalik and stegocephalians). Plesioth and Cephadrome (the “ambulichtyies”) share more characters with fishes than with tetrapods. More recent games of the franchise have creatures that could change the topology of the tree into a more Earth-like tree of vertebrate evolution, like Climbing Joyperch, which is very similar to Tiktaalik, and Petricanths in Monster Hunter World. Future complementary studies should highlight and resolve this “Monster Hunter Romer’s Gap”.

Tetrapod clade

As the sister group to the “ichtyan” clade, the consensus tree (Fig. 1) shows a group with four-limbed creatures, similar to the Earth’s Tetrapoda clade (Fig. 4). This one is supported by the occurrence of chiridian limbs (i.e. with joints and digits), atlas vertebra and lacrimal canals, observable in humans, pigs, and frogs. Like on Earth, amphibians (represented here by the frog) are the most basal tetrapods, due to the lack of an amniotic shelled egg (Benton, 2014). Frogs also have a sprawling quadruped locomotion in opposition to the other tetrapods, which present an erect posture.

The other taxa in the tetrapod-like group form a clade based on the production of amniotic eggs, observed in humans, pigs and highly suspected in Apceros, Aptonoth, and Rathalos. Digits, four at forelimbs and hindlimbs, end in claws. These characteristics tend to compare this clade with the real-world amniote clade. However, in opposition to real amniotes, these of Monster Hunter show an ancestral and common endothermy. On Earth, heat production strategies appeared independently in therapsids and archosaurs (Legendre & Davesne, 2020).

The amniote clade is divided into three subunits: the theropod-like clade, the mammal-like clade and the wyverns. We also observe that Fatalis is alone at the same branching level. Its scrawling locomotion, the ancestral type in tetrapods, prevents it from being included in one of the other clades with erect locomotion (via convergence). Its supplementary pair of chiridian limbs, forming wings on its back, are a unique autapomorphy and does not permit exact classification. On Earth, no vertebrate species has six limbs. A plausible hypothesis to explain these extra arms can be an abnormal expression of homeotic genes during the embryo development, duplicating the forelimbs. However, supernumerary limbs also need to be functional with their own nervous system and brain modifications, such as the sensory cortex to touch, the motor cortex to move, and the cerebellum for coordination.

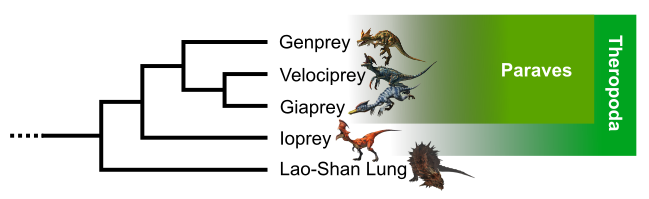

Theropod clade

Within the tetrapod group, Genprey, Velociprey, Giaprey, Ioprey, and Lao-Shan Lung form a clade based exclusively on the occurrence of a dewclaw on the hindlimbs (Fig. 5). Quadruped locomotion is the ancestral type visible on Lao-Shan Lung, the most basal taxa of the clade. All the others possess prograd bipedality and a reduction of the forelimbs, similar to theropods from Earth. Genprey, Velociprey and Giaprey exhibit five digits on their hands in comparison to most basal taxa, which have four. Five fingers are visible on frogs (one is vestigial), the most basal taxa of the tetrapod clade. This fifth digit can be a recurrence of the lost digit, for example by homeotic genes reactivation. It can also be a newly-acquired “sixth” digit, fulfilling the same function of the ancestral lost digit. Finally, these three creatures have a raptorian claw on their feet, similar to the paravian dinosaurs like dromaeosaurs, troodontids and Balaur (Hendrickx et al., 2015).

Even though it was not used as a character in the analysis, Ioprey, Genprey, Velociprey and Giaprey all display social behavior, living in packs led by an alpha. Gregariousness seems to be a synapomorphy of this clade.

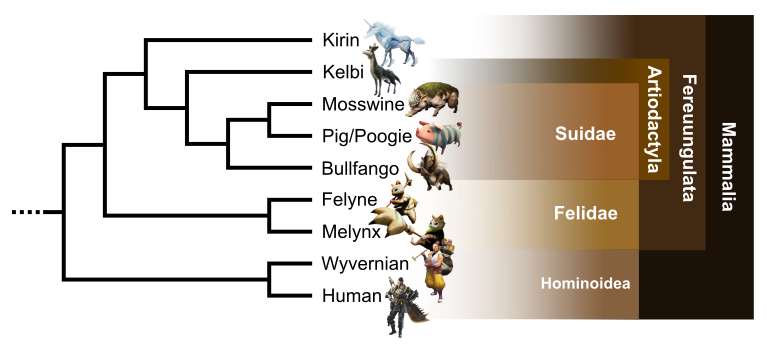

Mammalian clade

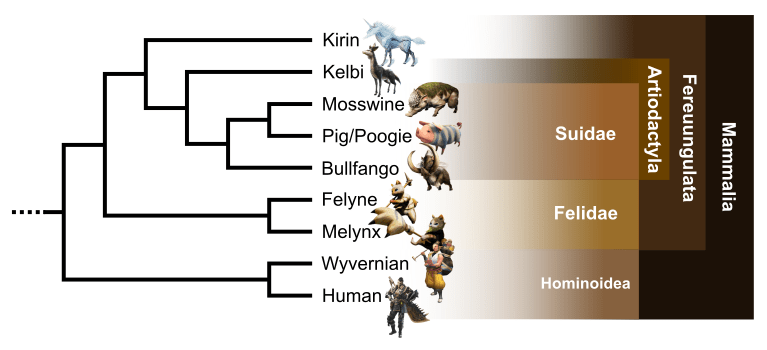

A mammalian clade appears in the big amniote group (Fig. 6). This one is defined by a viviparous reproduction, a heterodont and bunodont dentition, and lips. All taxa of this clade present an outer ear visible by an auricle and the occurrence of hairs and fur. Some characters are only visible on humans and pigs, such as nipples and placenta occurrence, though they are suspected on others by parsimony. Lastly, all of them present loss of scales. This well-resolved clade is very similar to Earth’s placental mammals phylogenetic tree (Kitazoe et al., 2007; Song et al., 2012).

We find firstly human and wyverian forming a humanoid clade based on orthogrady, bipedality, and disappearance of the tail. This clade is the sister of a second one, containing feline taxa and ungulates. This Feruungulata-like clade is defined by the occurrence of a rhinarium, ears situated highly on the head and a digitigrady of anterior members.

In felids, formed by Melynx and Felyne, we observe secodont teeth in association with their carnivorous diet, retractable claws and whiskers. In opposition, the euungulates are herbivorous with bunodonty. They also present a distinctive unguligrady locomotion and a reduction of the tail. As on Earth, we observe a clear distinction between perissodactyls (with Kirin and mesaxonian unguligrady) and artiodactyls (with paraxonian unguligrady). The latter have also a reduction of the inner and outer digits, forming two dewclaws.

To conclude, Bulfango, Mosswine and pigs present a snout, a character distinctive of suids. Pigs, the only domesticated taxa of this study, seems to have Mosswine as wild ancestor, sharing with it a hairless pink skin.

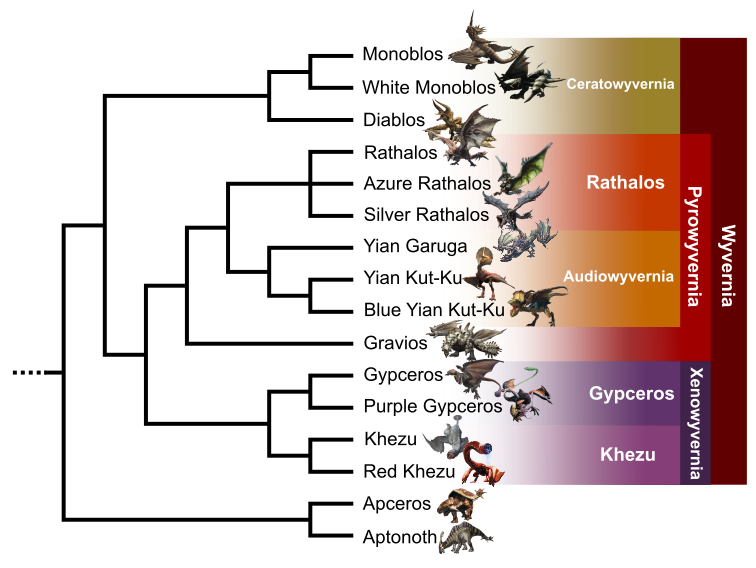

Wyvernian clade

Dragon-like creatures form a huge clade within the tetrapod one (Fig. 7). The included taxa (Rathalos, Diablos, Monoblos, Yian Kut-Ku, Yian Garuga, Gravios, Gypceros, Khezu and their subspecies) share in common a prograd bipedality. They also have the capacity of flying, with forelimbs transformed into wings with dactylopatagium and plagiopatagium. However, this clade has a quadrupedal origin, represented in the tree by the two herbivorous Aptonoth and Apceros. These two taxa also share with wyverns the occurrence of upper and lower rhamphotheca forming a beak. The tail ends with osteodermic caudal structures like a stegosaur’s thagomizer or an ankylosaur’s tail club. Furthermore, they share the production of amniotic eggs with shell.

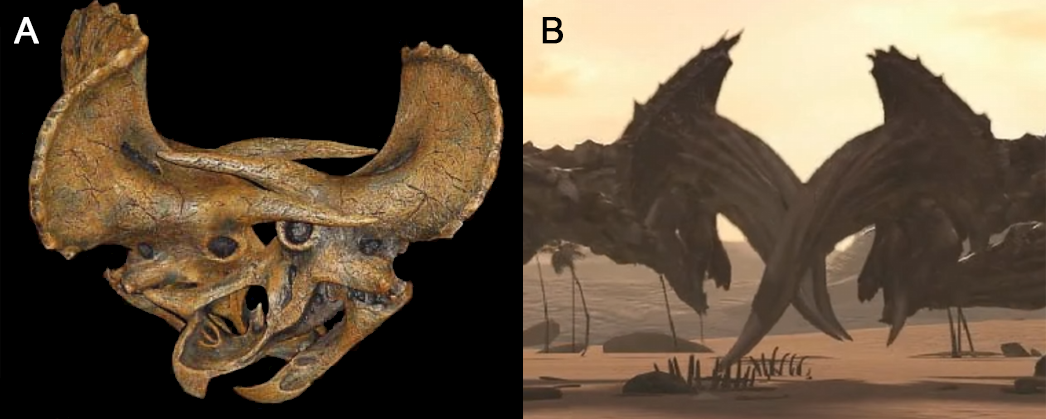

Diablos, Monoblos and white Monoblos form a first inner group that I called Ceratowyvernia. These three taxa have in common a skull extension in a frill, ornated by epiparietal bones. It is possible that this bony structure has a display function during male-to-male fights or reproduction, as suggested in ceratopsian dinosaurs (Fig. 8) (Farke, 2004; Fark et al., 2009), hence their name Ceratowyvernia (“Horned wyverns”). In the elongation of the frill, a scapular shield protects the neck’s base and the back’s front.

Ceratowyvernia also present, on the feet, a migration of the inner digit to the back of the feet with an almost complete anisodactyl position. Anisodactyly is generally presented in arboreal animals for perching, like real-world songbirds. However, anisodactyly is also present in some cursorial birds and it seems to be a foot morphology enabling an ecological flexibility that allows some birds to cope with environments with strong aridification periods (Raikow & Bledsoe, 2000; Martin & Sherratt, 2023). Monoblos, White Monoblos and Diablos live in deserts and semi-deserts. However, these environments seem to be relatively stable and not quick to change. Another explanation of this morphology in Monoblos and Diablos could be behavioral. Martin and Sherratt (2023) showed that, in Australia, some birds present a light anisodactyly to propel them in water by paddling, such as the grey teal Anas gracilis, or swimming, such as the little penguin Eudyptula minor. Monoblos and Diablos are not semi-aquatic wyverns, but present fossorial behavior, using their head and strong forelimbs to dig and move underground. Anisodactyl feet could have been selected to aid propulsion in the soil.

Ceratowyvernia is the sister group of a clade defined by the occurrence of a pressurized pocket in the body. In Gypceros, Khezu and their subspecies, this organ is used to stock venom (in the former) or electrified mucus (in the latter). These taxa also present a scaleless skin and flexible tail, without a thagomizer, allowing whipping in Gypceros and sucking substrate in Khezu. I decided to call them Xenowyvernia because of their atypic appearance, locomotion and way of life.

Gravios, Yian Kut-Ku, Yian Garuga, Rathalos and their subspecies form a clade that I called Pyrowyvernia, referring to the pressurized organ containing a flammable substance used for hunting or defense. With the exception of Gravios, all of the others are carnivorous taxa. During their hypothetical evolution, they developed different morphological traits in that sense. Yian Garuga, Yian Kut-Ku and Rathalos subspecies have an anisodactyl foot selected to catch prey. They also possess a bony sting at the tip of the tail. This bone is hollow with a canal connected to a venom gland. This organ was, however, lost during the evolution of the group and is absent in Yian Kut-Ku and Blue Yian Kut-Ku, where only an atrophied bony sting remains. Yian Garuga, Yian Kut-Ku and Rathalos subspecies also develop efficient hearing, with the occurrence of a scale transformed in an auricle-like structure, convergent to the outer ear of mammals. This adaptation was further selected upon, with the apparition in Yian Garuga and Yian Kut-Ku of large, parabolic, somital and mobile ears to locate prey by sound. We choose to name this clade Audiowyvernia (“hearing wyverns”).

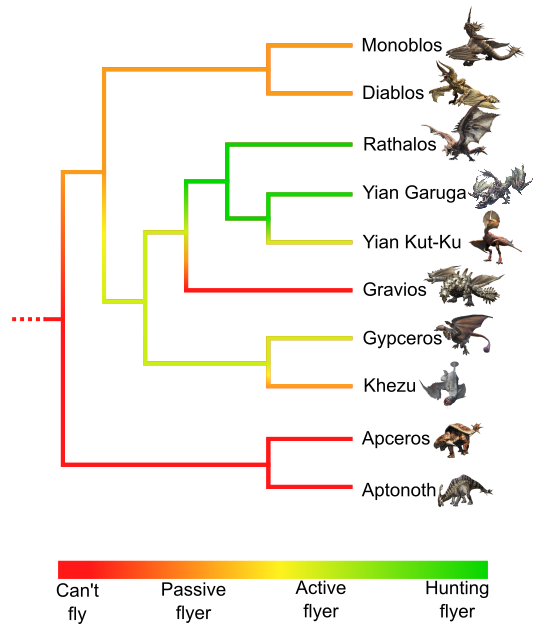

As previously mentioned, all wyverns in this study have wings, similar to those of bats, with patagium tensed between fingers and the flank. However, the occurrence of wings does not necessarily mean capacity of powered flight. Some wyverns, such as Rathalos, Yian Kut-Ku, Yian Garuga and Gypceros, are active flyers. They can fly away to change places, for example, and can even hunt prey (such as you, the hunter) from the sky, like the dive-bombing flight of Rathalos, inspired by birds of prey hunting techniques. On the other hand, some wyverns cannot fly high or for a long time. One example is the Khezu, which prefers to walk, even when moving away. Gravios is so massive that it can take flight only for a few seconds and a few meters above the ground. Diablos and Monoblos are not as massive as Gravios, and possibly could fly; however, they prefer walking or digging as locomotion.

The most parsimonious scenario tells of a progressive flying acquisition, from a wingless ancestor to a wyvern with wings but incapable of (or limited) powered flight, similar to Diablos and Monoblos (Fig. 9). Next, evolution would have selected flight that became a strong behavior in Gypceros, Yian Kut-Ku, Yian Garuga and Rathalos. This hypothesis suggests that patagium could appear before flight, making it an exaptation.

Although wings of wyverns are anatomically close to bat wings, it is difficult to use their evolutionary story as comparison. The oldest known bats, like Icaronycteris from the Eocene, already look like current ones, which does not allow us to fully understand the origin of flight in this mammal clade (Brown et al., 2019). Pterosaurs, the other vertebrate with patagium, are a similar story. Their strongly modified anatomy does not allow us to clearly and fully understand the origin of this group and, at the same time, their flight ability (Witton, 2013).

The only other group of flying vertebrates are birds. Since the discovery of Archaeopteryx (1861), different hypotheses have been made to explain the emergence of flight in this clade. Garner et al. (1999) proposed the “Pouncing model”, from an ambush predator ancestor. Williston (1879) and Ostrom (1979) proposed the “Cursorial model”, where wings were positively selected by accentuating stability on the run. Marsh (1880) proposed the “Arboreal model”, from an arboreal ancestor that soared from tree to tree. Today, scientists tend to think that these hypotheses do not exclude each other (Segre & Banet, 2018).

In the case of wyverns, the taxa from the first Monster Hunter games are heavy creatures, from hundred kilograms to several tons. The “Arboreal model” cannot be used to explain the emergence of flight; Monoblos and Diablos weigh several tons, so no tree could sustain that. The “Pouncing model”, from an ambush predator ancestor jumping from higher ground, is unlikely. The external group to wyverns, Apceros and Aptonoth, are herbivorous, as are the most basal wyverns, Diablos and Monoblos. Thus, the “Cursorial model” seems to be the most plausible; with the exception of Khezu, all wyverns are good runners, so it is possible that the origin of flight lies in this behavior. Studying other wyverns from more recent games, including the smaller ones, should allow us to confront this hypothesis and better understand the emergence of flight in the wyvern clade.

CONCLUSION

The bestiary of Monster Hunter is rich in diversity thanks to a series of successful games, born in 2004 with the eponymous game. Today, there are more than 300 in-game taxa, including predators and prey, and different species and subspecies. In this article, I tried to apply cladistic methodology to the bestiary from the first games, the so-called “First generation”, in order to obtain results with a historical, solid, and reproducible scientific method. The consensus tree presents great similarities with our planet’s tree of life. This can be easily explained by the large inspiration of creature designers in past and present nature. The cladistic method, by using the same polarization of states characters than on Earth, can also explain the similarity between this fictional fauna and the real-world one.

However, the weak representation of some taxa, like sarcopterygian and tetrapodomorph, resulted in meaningful differences to the evolution of vertebrates on Earth. Future studies, more focused on some clades and using taxa from all canon games, should be able to better develop some branches of the tree. Many novelties would be expected for the invertebrates, which were only represented in the first generation by insects. More recent games introduced new clades, such as crustacean-like creatures (Herminataur and Caenataur species), chelicerate-like ones (Nercyllia and Rakna-Kadaki species), and cephalopods (the cuttlefish-like Nakarkos and the octopus-like Nu Udra). Finally, in the tetrapod clade, more mammalian and reptilian taxa could result in a better resolution of the current polytomy; for example, the erect position that appears via convergence in mammals, theropods and wyverns, could be interpreted differently on a more detailed tree with more tetrapod-like taxa.

The fauna of the Monster Hunter franchise, with its rich lore and its strong Earth nature inspiration, can be a topic or reflection of evolutionary biology, as we saw in this article. In a more down-to-earth manner, it is also a good exercise for biology students and enthusiasts, allowing them to learn this method, its application, and also its limits. In the same thought exercise, the flora of the different biomes could also be studied. Further away, landscapes, minerals, and climates also give this franchise an interesting geoscientific content to explore.

REFERENCES

Benton, M.J. (2014) Vertebrate Palaeontology. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey.

Betancur-R, R.; Broughton, R.E.; Wiley, E.O.; et al. (2013) The tree of life and a new classification of bony fishes. PLoS Currents 5.

Brown, E.E.; Cashmore, D.D.; Simmons, N.B.; Butler, R.J. (2019) Quantifying the completeness of the bat fossil record. Palaeontology 62: 757–776.

Darlu, P. & Tassy, P. (1993) La Reconstruction Phylogénétique: concepts et méthodes. Editions Matériologiques, Paris.

Farke, A.A. (2004) Horn use in Triceratops (Dinosauria: Ceratopsidae): testing behavioral hypotheses using scale models. Palaeontologia Electronica 7(1): 1–10.

Farke, A.A.; Wolff, E.D.; Tanke, D.H. (2009) Evidence of combat in Triceratops. PLoS ONE 4: e4252.

Garner, J.P.; Taylor, G.K.; Thomas, A.L.R. (1999) On the origins of birds: the sequence of character acquisition in the evolution of avian flight. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 266: 1259–1266.

Hendrickx, C.; Hartman, S.A.; Mateus, O. (2015) An overview of non-avian theropod discoveries and classification. PalArch’s Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology 12: 1–73.

Kitazoe, Y.; Kishino, H.; Waddell, P.J.; et al. (2007) Robust time estimation reconciles views of the antiquity of placental mammals. PLoS ONE 2: e384.

Legendre, L.J. & Davesne, D. (2020) The evolution of mechanisms involved in vertebrate endothermy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 375: 20190136.

Marsh, O.C. (1880) Odontornithes: a monograph on the extinct toothed birds of North America. Vol. 1. US Government Printing Office, Washington.

Martin, E.M. & Sherratt, E. (2023) Grasping hold of functional trade-offs using the diversity of foot forms in Australian birds. Evolutionary Ecology 37: 945–959.

Misof, B.; Liu, S.; Meusemann, K.; et al. (2014) Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science 346: 763–767.

Ostrom, J.H. (1979) Bird flight: how did it begin? Did birds begin to fly “from the trees down” or “from the ground up”? Reexamination of Archaeopteryx adds plausibility to an “up from the ground” origin of avian flight. American Scientist 67: 46–56.

Page, R.D.M. (1998) Nexus Data Editor. R.D.M. Page, UK.

Segre, P.S. & Banet, A.I. (2018) The origin of avian flight: finding common ground. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 125: 452–454.

Raikow, R.J. & Bledsoe, A.H. (2000) Phylogeny and evolution of the passerine birds. BioScience 50: 487–499.

Song, S.; Liu, L.; Edwards, S.V.; Wu, S. (2012) Resolving conflict in eutherian mammal phylogeny using phylogenomics and the multispecies coalescent model. PNAS 109: 14942–14947.

Steppan, S.J.; Meyer, A.A.; Barrow, L.N.; et al. (2022) Phylogenetics and the evolution of terrestriality in mudskippers (Gobiidae: Oxudercinae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 169: 107416.

Swofford, D.L. (2003) PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods). Sinauer Associates, Sunderland.

Witton, M. (2013) Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

About the author

Christopher Sevin, MSc., is a French independent scientific educator. Graduated with a Masters’ degree in Vertebrate Paleontology, he works in scientific communication, cladistics applied to pop culture and the evolution of the Limagne Basin (France) during the Oligocene–Miocene transition.