Stephan Lautenschlager1,2 & Thomas Clements3

1School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK.

2The Lapworth Museum of Geology, Birmingham, UK.

3GeoZentrum Nordbayern, Friedrich-Alexander Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany.

Emails: s.lautenschlager (at) bham (dot) ac (dot) uk, clements.taph (at) gmail (dot) com

In the first act of ‘Star Wars: Return of the Jedi’ (ROTJ), the protagonist, Luke Skywalker, infiltrates the palace of the notorious crime lord, Jabba the Hutt, while seeking to free his allies from captivity. After a short discussion and a failed assassination attempt, Luke and an unfortunate Gamorrean, fall through a trap door triggered by Jabba and find themselves in a large dusty cavern strewn with bones. Here, a gigantic metal blast door slowly rises revealing Jabba’s pet monster: a large male Rancor – a 5-meter tall, bipedal, reptilian creature (Starwars.com; Fig.1).

After grabbing and devouring the Gamorrean in a series of bites, the Rancor turns to find its next prey. In desperation, the young Jedi grabs a large (mammalian?) femur to protect himself, only to be grabbed by the Rancor and lifted towards an ignominious end as a Rancor snack. Just as the Rancor goes to bite Luke, he lodges the femur in its jaw lengthways, forcing the Rancor to drop him and recoil. Despite the Rancor having opposable digits that are capable of holding and manipulating objects, the Rancor closes its jaw, causing the femur to splinter, eventually snapping in half. This is a fantastic biomechanical feat – typically mammalian femurs have evolved to resist high levels of vertical loading, and in many terrestrial mammals, including humans, the femur is often the largest and strongest bone in the skeleton (Erickson et al., 2002).

The ability of the Rancor to snap the femur with apparent ease poses interesting questions: (1) how much dorso-lateral force is required to snap a femur of the size used by Luke to stave off the Rancor in ROTJ? (2) Could the Rancor generate such force with its jaws? Lastly, (3) could any other extinct or extant organisms generate such force?

Despite the fact that Rancor exist(ed?) a long time ago in a galaxy far, far, away, there are techniques employed in paleontological research that can answer the questions outlined above. The only direct evidence we have of ancient organisms is their fossilised remains. However, fossils are not truly representative of the organism as it was in life; after death, the processes of decay act to strip biological information from the carcass. Typically, soft tissues are lost rapidly, leaving only the ‘hard’ biomineralised tissues such as bones, teeth, or shells to persist long enough to become geologically stabilised as fossils (see Clements & Gabbott, 2022). However, the hard tissues are also subject to a range of destructive processes that commonly result in fragmentation and deformation of the organisms’ remains. These complex processes of fossilisation can make it difficult to make accurate inferences about what ancient creatures looked like and how they lived, especially if the organismal group is extinct and/or has no modern analogues for direct comparison (see Lautenschlager, 2016).

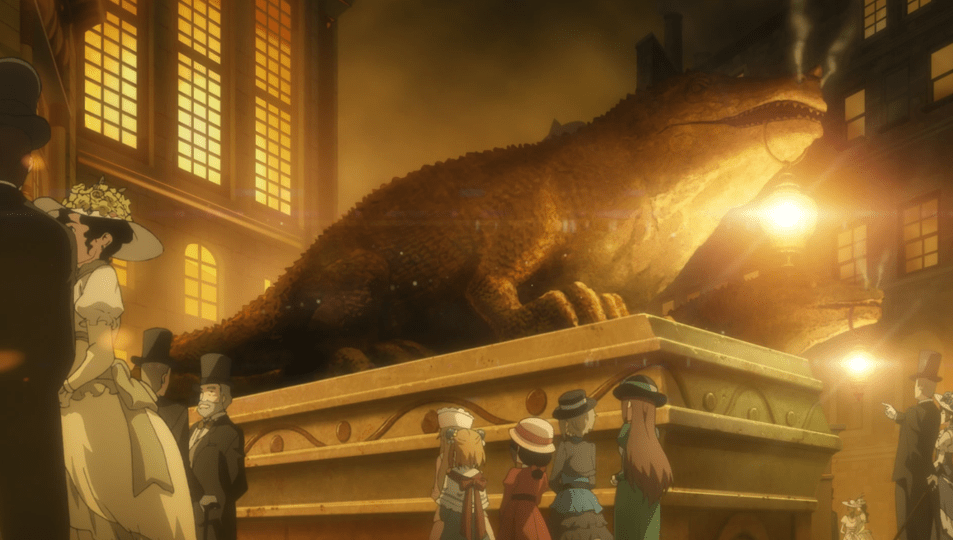

Yet despite this, palaeontologists are incredibly adept at incorporating advanced analytical methods developed in other sectors to unlock the biological information stored in stone. One common example is the use of Finite Element Analysis (FEA) in palaeontological investigations (Rayfield, 2007; Bright, 2014). Originally designed by civil engineers to simulate and predict the deformation of objects with complex geometries, palaeontologists now regularly use FEA to investigate the biomechanical properties and functional capabilities of fossilised skeletal remains – allowing unparalleled understanding of the bite force of charismatic ancient predators, such as Tyrannosaurus rex (Rayfield, 2004; Fig. 1a2), the sabre-tooth cat Smilodon fatalis (Figueirido et al., 2024), the carnivorous fossil whale Basilosaurus isis (Snively et al., 2015), giant pliosaurs (Foffa et al., 2014), and the so-called “terror bird” Andalgornis steulleti (Degrange et al., 2010).

Typically, FEA is undertaken by creating digital three-dimensional models of fossil skeletons either by computed tomography (CT) scanning, laser scanning, or photogrammetry (Cunningham et al., 2014; Sutton et al., 2014; Diez Diaz et al., 2021). Soft tissues, such as muscles, nerves, blood vessels, etc., can be reconstructed using various techniques to create a musculoskeletal model which can then be incorporated into FEA (see Lautenschlager, 2016). In the case of the Rancor, there are no canon diagrams of the skeleton, only videos and pictures of the animal complete with soft tissues – actually the inverse situation of palaeontological investigations. However, in many palaeontological studies, fossils are not always available or accessible to be digitised, e.g., when fossil specimens are in collections in remote locations, or are too fragile to be transported, or have been destroyed/lost. In such cases, 3D models can be created from scratch in a digital environment using a so-called box-modelling approach. In this scenario, models are created from simple geometries and subsequently refined following a sketch or photograph as template (Rahman & Lautenschlager, 2016). Here, we utilise these techniques to reconstruct the cranial skeleton of the Rancor and assess its bite force ability using Finite Element Analysis.

METHODOLOGY

Rancor morphology and behaviour

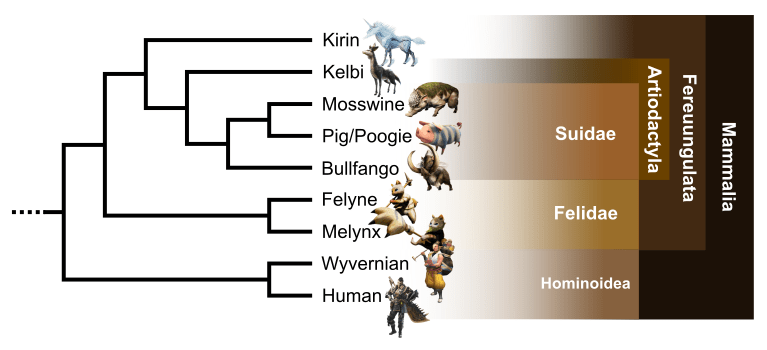

Since their introduction in ROTJ, Rancor have become a commonly recurring organism in the Star Wars franchise. Native to Dathomir, a temperate planet found within the Outer Rim Territories (Fry, 2019), Rancor are described as ‘reptomammals’ within the Star Wars universe – reptilian organisms that have evolved mammalian traits (Whitlatch & Carrau, 2001). Rancor do not have scaly skin, rather a thick ‘leathery’ hide that is known to be able to resist high energy blaster fire and projectile weapons (Sansweet, 1998). Rancor are reported to be endothermic, and lay clutches of egg pairs. While Rancor have been reported to demonstrate parental care (in a similar vein to some crocodiles), they do not suckle their young – although it should be noted that it is not clear whether they can lactate (Whitlatch & Carrau, 2001). Here, we assume that Rancor are reptiles.

Rancor (and the several subspecies) are large bipedal carnivores characterised by short stocky legs and long arms that terminate in hands with four distinct digits: the first, second, and third are elongate and tipped with sharp claws, while the fourth digit is vestigial. In ROTJ, the male Rancor (named Pateesa; Bray et al. 2015; Fig. 1b) walks upright in a slow and lumbering manner. We now know this is not usual for Rancor: Pateesa is housed within a cavern with no natural light that is far too small for such a large predator. In later books, Luke Skywalker indicates that he believes that Pateesa was malnourished and abused during its captivity in Jabba’s palace (Anderson & Moesta, 1995; see also Perrin, 2002). This hypothesis is supported by the appearance of a juvenile Rancor in The Book of Boba Fett (Ch. 7: In the Name of Honor; Fig. 1d). This individual demonstrates that Rancor have a quadrupedal gait, similar to knuckle walking used by Gorillas (although Rancor use the palm of their hand, and not their knuckles) to rapidly and nimbly negotiate complex three-dimensional terrain. Moreover, Rancor demonstrate a high level of coordination when using their long arms and opposable digits to grasp and manipulate objects, allowing them to nimbly capture fleeing prey (such as unfortunate Gamorreans) or to expertly undertake complex tasks such as dissembling battle droids (Fig.1d).

One aspect of Rancor is that the head is extremely large for their body size, yet they have strikingly flattened facial features including a pair of large nostrils inset between two small eyes, and a mouth lined with sharp teeth (often demonstrating malocclusion), however, as far as we know, there are no official canon reconstructions of the skeleton or the skull. There are two interesting Rancor facts that may impact our ability to model the cranial anatomy: 1) in ROTJ, the top of Pateesa’s head inflates and deflates as it is breathing – implying that there may be some sort of dorsal skull opening that is covered by dermis. However, this is not seen in the Rancor from The Book of Boba Fett and is unconfirmed. Perhaps this structure acts as a vocal sac (e.g., similar to some frogs), but this is speculative. For the purpose of this work, we will not factor in this unique cranial arrangement. 2) Despite their reputation as mindlessly vicious hyper-predators, Rancor are known to be social, emotionally complex (Fig. 1c), and sentient organisms capable of forming complex social hierarchy and being able to communicate oral traditions and histories to each other (e.g., Windham, 2007). However, determining brain-to-body mass ratios is difficult across the animal kingdom, and unlike palaeontological work using skulls, we are unable to model brain size in our reconstructions.

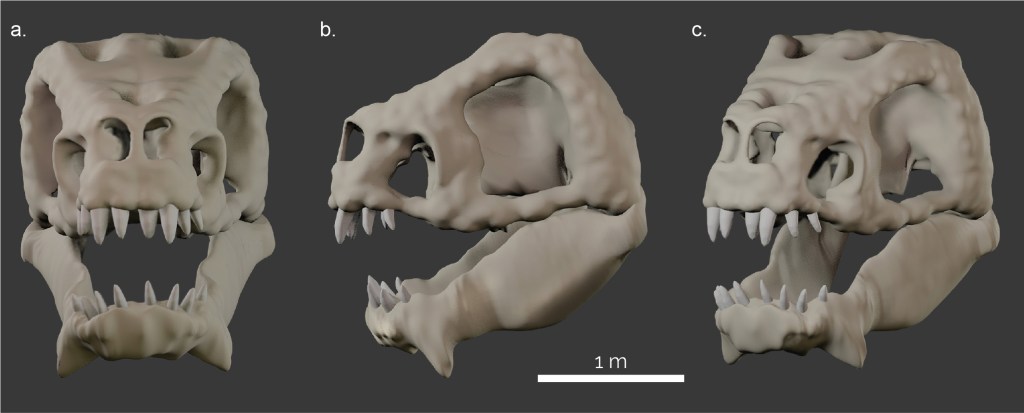

Reconstructing the skull of a Rancor

The skull of the Rancor was reconstructed using the ROTJ model (created by Phil Tippet) as a reference (Fig. 1b). Assuming an anatomy similar to archosaurs found on Earth (e.g. dinosaurs, crocodiles, and birds), we believe it would be likely that the skull would be similar to their life appearance without extensive facial muscles, fat pads and other soft tissues substantially obscuring the skull morphology. Further, we assumed that, as a generic reptile-like organism, the Rancor skull shows a diapsid condition (all assuming that Star Wars creatures loosely follow the known organismal classification). Diapsids possess two temporal openings (=fenestrae) at the side of the skull; in contrast to mammals and their ancestors with one temporal opening, and turtles which have no temporal openings.

In order to study the musculoskeletal morphology and function of any animal using computer simulations, a digital model of the skeleton is required. In the absence of a preserved (or drawn) skull, we reconstructed the skull using the box modelling approach (described above) to model the hypothetical skull and lower jaw of a Rancor using Blender 2.9 and 4.2 (blender.org) (Fig. 2). This model then served as the basis for the soft-tissue reconstructions and biomechanical analyses (below).

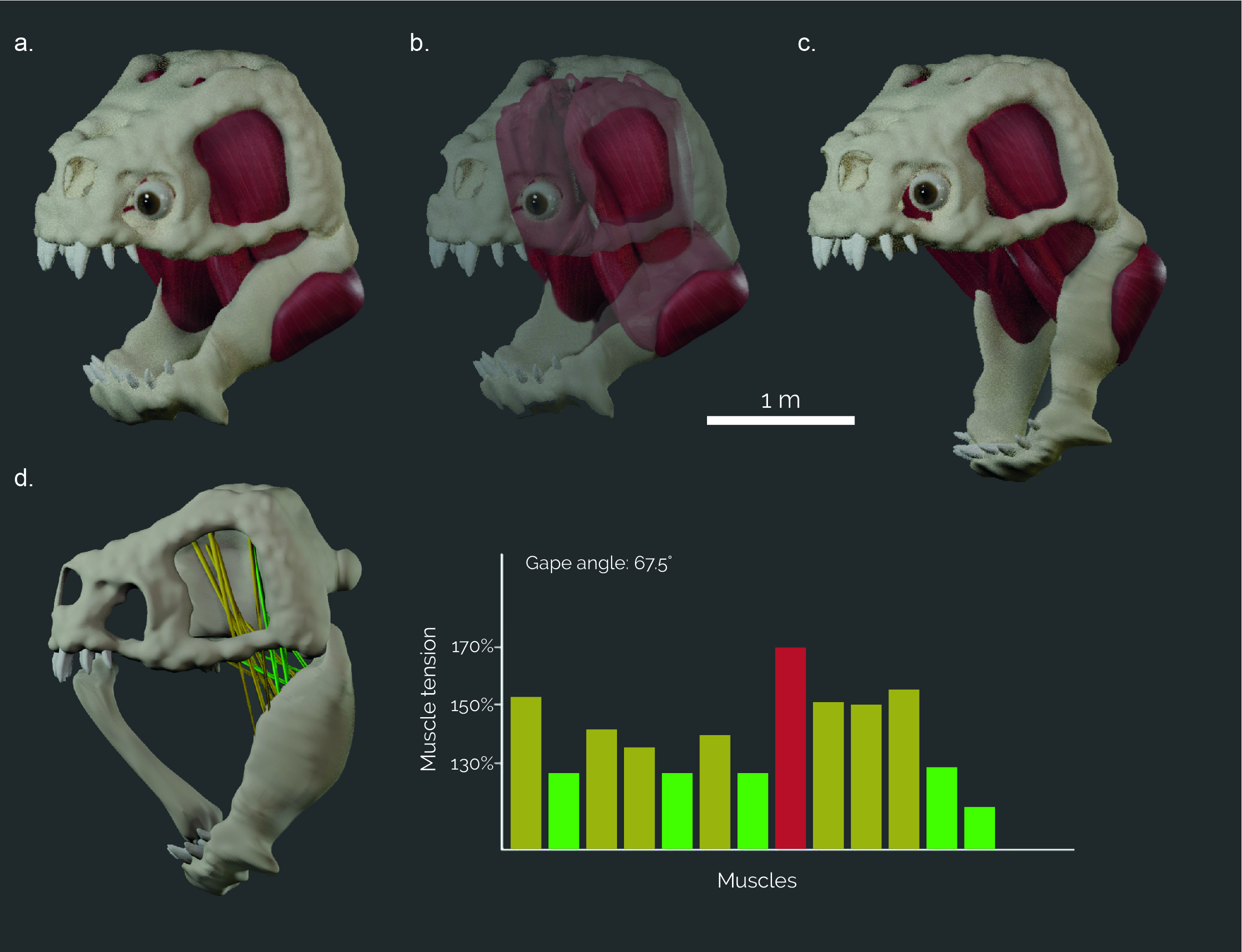

Cranial muscle reconstruction

Detailed knowledge about the size and arrangement of the jaw musculature is required to estimate bite forces accurately and to provide input forces for biomechanical simulations. The number and position of the jaw closing muscles vary between different animal groups. As the Rancor is a reptile, we reconstructed eight separate pairs of jaw closing muscles, typical of fossil and modern reptiles, such as crocodilians, birds and dinosaurs. All muscles were reconstructed digitally by first identifying the hypothetical attachment sites on the skull and the lower jaw (following the method outlined in Lautenschlager, 2013, 2016). Although these muscle attachments are unknown in Rancor, similar patterns are observed across different extinct and extant vertebrate groups allowing educated inferences to be made. In a next step, corresponding attachment sites were connected digitally by simple point-to-point connections. This allowed identifying intersections between muscles, or between muscles and bone, that require manual adjustment of the connections. In a final step, the simplified connections were fleshed out to create the full muscle bodies (Fig. 3a–c). These steps were performed in Blender 2.9 and 4.2.

Gape analysis

Once the muscles have been modelled, it is possible to assess the gape of the Rancor. Gape, in this context, refers to the ability of an organism to open its jaw and is measured as the angle of the lower jaw relative to its closed position. To do this, the skull and mandible models were joined at the jaw joint and the mandible was allowed full rotation around the mediolateral axis (y-axis) to simulate sagittal opening and closing. Adductor muscles were represented by cylinders connecting the attachment sites. An opening motion with a step size of 0.5° was imposed on the lower jaw, during which the muscle cylinders were stretched. For each step, the ratio between the resting length and the extended length of the muscle cylinders was calculated until any of the muscle cylinders reached the critical extension limit of 170%; a limit based on experimentally derived values above which tetanic tension of mammalian adductor muscles is no longer possible (Lautenschlager, 2015).

Biomechanical analyses

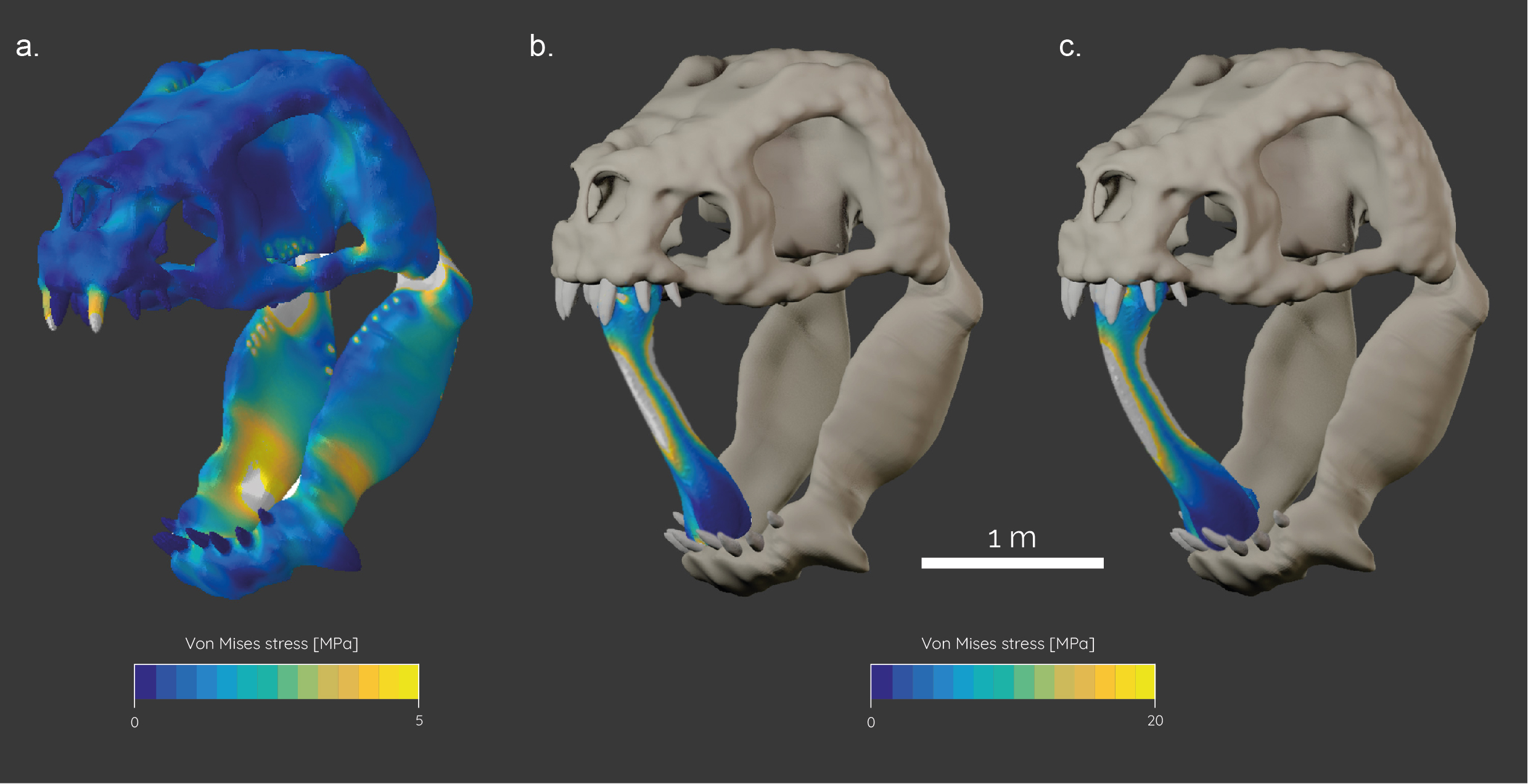

In order to evaluate the biomechanical capabilities (e.g. bite forces, stress resistance) of the Rancor, the skull model was subjected to finite element analysis (FEA). FEA is a computational engineering method that calculates the stress distribution and behaviour of objects in response to external load forces.

In preparation for the FEA, the skull and mandible models of the Rancor were imported into Hypermesh (Altair, v. 11) for solid meshing and the setting of boundary conditions. The final models consisted of ca. 700,000 elements for the skull and 450,000 elements for the mandible. The models were assigned material properties for Alligator bone (E = 15,000 MPa, v = 0.29) (Porro et al., 2011) and teeth (E = 60,400 MPa, v = 0.3) (Creech, 2004) in an approximation of likely material properties for the Rancor. In a next step, constraints were added to the jaw joint (six nodes on each side) and the occipital condyle (five nodes) to fix the model from rigid body movement. Further, one node was constrained on the second tooth in the upper jaw and the posteriormost tooth on the lower jaw to record reaction forces (=bite forces). Muscle forces were added as individual load vectors to the model to replicate muscle action.

To test the hypothesis that the bite performance of the Rancor is sufficient to break a long bone with its jaws as depicted in ROTJ, a generic model of a long bone with a length of 1.5 meters was generated. We ascertained the approximate size of the long bone used by using the height of actor Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker) as a scale (see Fig. 1). It is important to note that the leg bone used by Skywalker is much larger than any extant mammal found on Earth today – to our knowledge the organism that yielded the bone has never been taxonomically identified in the Star Wars literature. The bone model was meshed accordingly and assigned the same material properties for mammalian bone (E = 10,000 MPa, v = 0.4) (Rayfield, 2007). It was subsequently subjected to load forces equivalent to the resultant bite forces of the Rancor model.

All models were imported into Abaqus (Simulia, v. 6.141) for analysis and post-processing. Biomechanical performance was assessed via von Mises stress contour plots and reaction forces measured at the tip of the teeth. The final FEA models consisted of ca. 750,000 elements for the skull model, ca. 500,000 elements for the lower jaw, and ca. 150,000 elements for the isolated long bone. Models were solved on a Windows PC with Intel core i7 processor, 32 GB RAM, and an Nvidia GeForce mx350 2GB graphics card. Solving times for the individual models took between 10 and 20 minutes.

RESULTS

The reconstruction of the jaw musculature allowed an estimate of the overall muscle force, yielding an overall force of 116,000 N. Due to the vertebrate jaw being a third-class lever, with the muscle force situated between the jaw joint and the bite point, the resultant bite force is typically a lot lower. Measurements from the finite element models resulted in a bite force of ca. 44,000 N for the Rancor. The digital models of the cranial skeleton and the musculature further allowed estimating the maximum gape angle based on muscle tension. Maximum achievable gape was found at an angle of 67.5˚.

The evaluation of stress distribution following a bite with maximum muscle contraction shows relatively low stresses in the skull and somewhat higher stresses in the lower jaw. In the latter, stress hotspots are found anteriorly just behind the tooth row and at the posterior region of the jaw at the muscle attachment sites. This is to be expected as the lower jaw represents an elongate beam that is subjected to bending due to the muscle and bite forces.

The biomechanical analysis of the mammalian femur under load showed that the bone experiences high stress values (up to 200 MPa) in the midshaft region. The femur is predominantly subjected to compressive stresses due to the bite force acting at both epiphyses which consequently leads to bending of the bone. This force exceeds the bending strength for most vertebrate bones, such as Alligator femora (Currey, 1987; Erickson et al., 2002) and is within the yield limit of human long bones (Turner & Burr, 1993).

DISCUSSION

The FEA modelling (with the caveat of some major intergalactic anatomical assumptions) indicates that the Rancor’s bite strength is more than capable of vertically snapping a large long bone and that the skull of the Rancor could easily tolerate such loadings. We, therefore, suggest that, in a life threatening situation, utilising a long bone to prevent the Rancor from devouring you can only be relied upon as a temporary measure – in the specific case of Luke’s encounter with the Rancor, the usefulness of a long bone is likely further diminished by the desert climate of Tatooine: bones that are ‘dry’ are known to have a lower bending strength and are more brittle than fresh or wet bones (Curry, 1988).

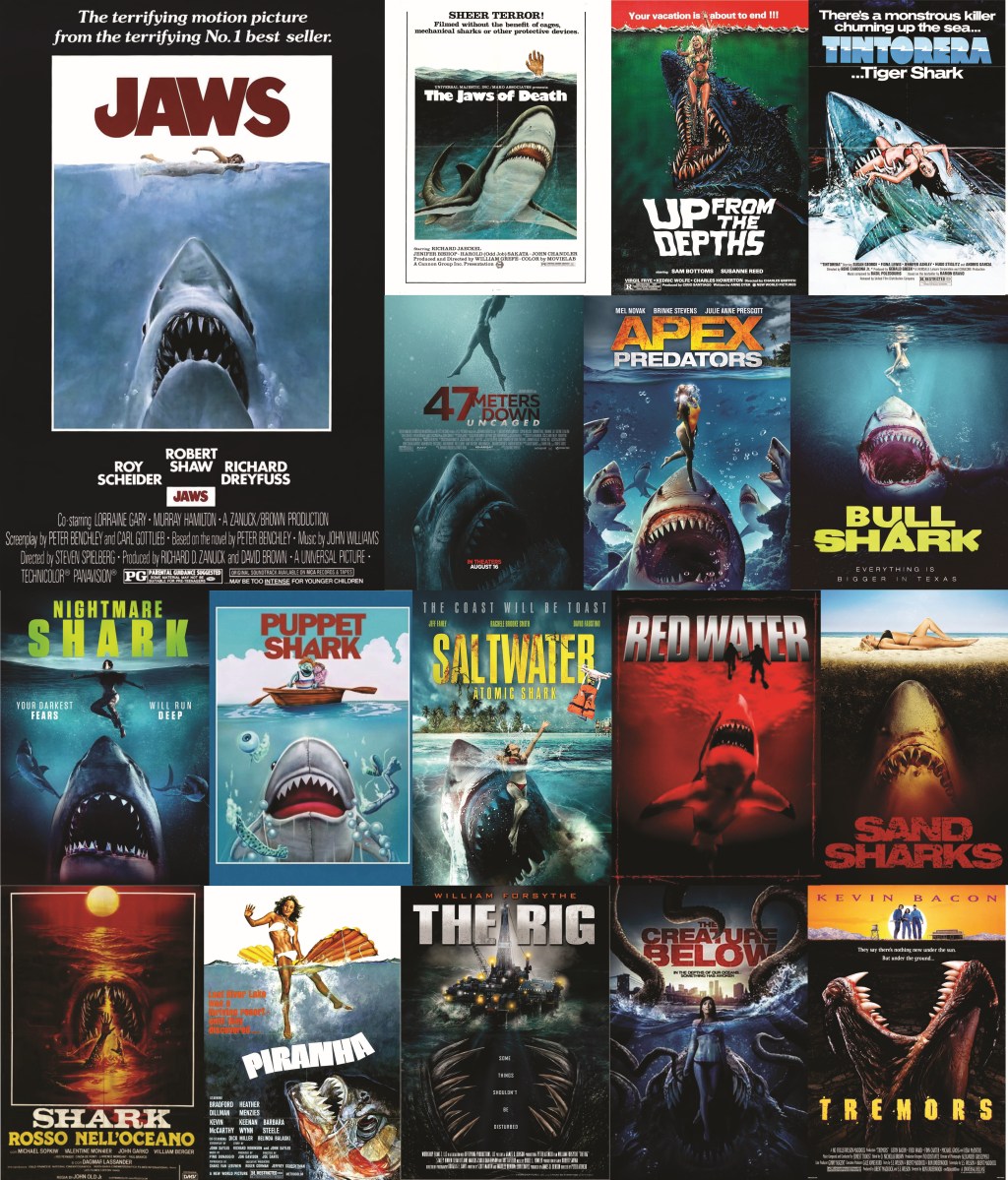

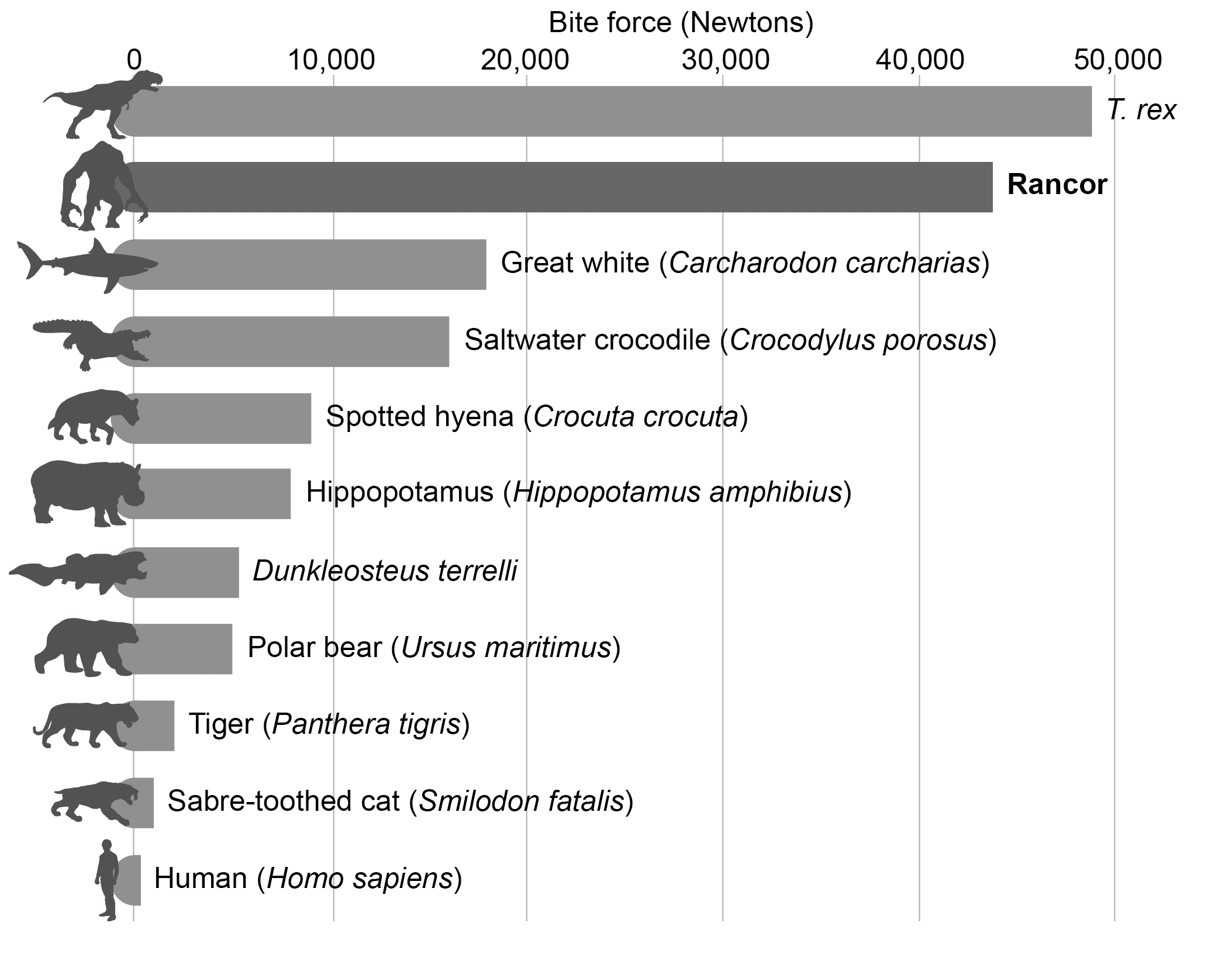

How does the Rancor’s bite force compare to other known organisms? Our data suggests that no living vertebrate’s bite force comes close to the Rancor (Fig. 5). It is estimated that the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) has the strongest bite force of an extant organism, determined to be over 18,000 N (Wroe et al., 2008). However, the highest bite force measured is from the Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) exerting around 10,0000–16,000 N of pressure (Erickson et al., 2012, 2014). Iconic terrestrial mammalian predators typically have lower bite forces – the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) has a bite force of ca. 9,000 N (Meers, 2002). The largest bear species, the polar bear (Ursus maritimus), can generate bite forces of around 5,000 N (Slater et al., 2010), while large cats such as the lion (Panthera leo) and the tiger (Panthera tigris) achieve bite forces of ca. 1,500–2,000 N. Surprisingly, mammalian herbivores/omnivores have high documented bite forces – gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) can generate bite forces of ca. 5,000 N (Eng et al., 2013) while the hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) have bite forces of ca. 8,000 N (Haddara et al., 2020). Human beings (Homo sapiens) have a bite force of ca. 150–300 N during typical mastication but can reach bite forces of up to 700 N (Takaki et al., 2014).

In terms of extinct organisms, the Rancor’s bite force sits amongst the charismatic predatory theropod dinosaurs. Sakamoto (2022) suggests that some mega-carnivorous theropods had a lower bite force than the Rancor; e.g., Spinosaurus aegyptiacus (ca. 12,000 N), Carcharodontosaurus saharicus (ca. 17,000 N) and Acrocanthosaurus atokensis (ca. 26,000 N). However, while estimates vary significantly, the proposed bite force for the iconic Tyrannosaurus rex typically ranges between 18,000 and 35,000 N (e.g., Rayfield, 2004; Gignac & Erickson, 2017) with some studies suggesting higher values (ca. 49,000 N; Sakamoto, 2022). These values, alongside fossil evidence such as bite marks (Erickson and Olson, 1996) and coprolites (fossilised faeces) with high proportions of bone fragments (Chin et al., 1998), suggest that T. rex was easily capable of crushing and consuming bone, akin to the Rancor (e.g., Gignac & Erickson, 2017; Sakamoto, 2022). FEA has also been undertaken to assess the bite force of other iconic palaeo-predators, such as giant Devonian placoderm Dunkleosteus terrelli (ca. 5,300 N; Anderson & Westneat, 2007) and the famous sabrecat Smilodon fatalis (ca. 1,000 N; McHenry et al., 2007), however, these organisms have much lower bite forces than the theropod dinosaurs (and the Rancor).

Digital modelling and simulation techniques have considerably changed how extinct organisms can be studied and contributed a wealth of new data that would otherwise be difficult to obtain. This study follows the same methodological approach and is not fundamentally different from the investigation of the functional morphology and ecology of fossil vertebrates. In both fossils and intergalactic predators, such as the Rancor, it is very dangerous (or impossible) to take in vivo measurements and to observe behavioural aspects. Digital analyses can, therefore, provide additional information and permit non-invasive hypotheses-testing approaches. However, despite the versatility of digital investigations, there are some uncertainties inherent to these techniques that should be considered. Firstly, muscle reconstructions follow modern examples and assume similar muscle arrangement and architecture for fossil/intergalactic vertebrates. While muscles are fairly conserved across different animal groups (Hirasawa & Kuratani, 2018), individual differences in the number of muscle fibres, fibre length, and muscle pennation (i.e. muscle fibres attaching to tendons rather than directly to skeletal elements) etc. can change the maximal possible muscle force and tension. It is therefore likely that digital muscle reconstructions underestimate overall muscle forces due to the difficulty in reconstructing the internal muscle architecture. Secondly, for functional analyses, such as FEA, certain simplifications and assumptions have to be made. Similar to muscles, bone is generally similar across a wide range of vertebrate groups (Huttenlocker et al., 2013). However, some vertebrates may have evolved specific adaptations: for example, bird bones are lightweight and hollow to facilitate flight, while aquatic species (e.g., whales and their ancestors) typically have adapted to the need for buoyancy with the development of dense and compact bones (Houssaye, 2022). It is therefore important to use correct material properties reflective of a species’ bone architecture for functional simulations (Bright, 2014).

While such material properties are known for more commonly studied vertebrates, obtaining the same for fossil/intergalactic species is challenging – with fossil material, the original bone has been replaced and remineralised during the fossilisation process. Therefore, using material properties from closely related or functionally equivalent species can minimize uncertainties but, similar to muscle reconstructions, the skeletal stability may be underestimated. Regardless of these uncertainties, the results from this study demonstrate that the Rancor could exert some of the bite forces larger than most organisms that have existed on Earth – easily capable of breaking robust long bones inserted into its jaw longitudinally – a feat not commonly replicated in nature. Moreover, our model indicates that the skull and lower jaw of the Rancor experienced relatively low stresses that would not pose a risk of damage to its own skeleton.

CONCLUSION

By reconstructing the skeletal anatomy and using Finite Element Analysis, a technique commonplace in palaeontological science, we have estimated the bite force of the iconic Rancor, the intergalactic predatory ‘reptomammal’ from Return of the Jedi. We estimate that the Rancor would have been able to generate a bite force of ca. 44,000 N. This value far exceeds the strength of bone, indicating that the Rancor to easily snap a large mammalian femur that had been placed longitudinally in its jaw. Moreover, our model demonstrates that the Rancor’s skull and jaw would have been able to withstand the stresses exerted on them as the long bone shattered. While our model relies on several assumptions (some typical of palaeontological research and some due to the intergalactic nature of this study), we suggest that the Rancor’s bite force far exceeds any extant organism and is comparable to the large predatory theropod dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus rex.

REFERENCES

Anderson, P.S. & Westneat, M.W. (2007) Feeding mechanics and bite force modelling of the skull of Dunkleosteus terrelli, an ancient apex predator. Biology Letters 3: 77–80.

Anderson, K.J. & Moesta, R. (1995) Shadow academy. Boulevard Books, New York.

Bright, J.A. (2014) A review of paleontological finite element models and their validity. Journal of Paleontology 88: 760–769.

Chin, K.; Tokaryk, T.T.; Erickson, G.M.; Calk, L.C. (1998) A king-sized theropod coprolite. Nature 393: 680–682.

Clements, T. & Gabbott, S. (2021) Exceptional preservation of fossil soft tissues. eLS 2: 1–10.

Creech, J.E. (2004) Phylogenetic character analysis of crocodylian enamel microstructure and its relevance to biomechanical performance. Florida State University, Tallahassee. [Unpublished Master thesis]

Cunningham, J.A.; Rahman, I.A.; Lautenschlager, S.; et al. (2014) A virtual world of paleontology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 29: 347–357.

Currey, J.D. (1987) The evolution of the mechanical properties of amniote bone. Journal of Biomechanics 20: 1035–1044.

Currey, J.D. (1988) The effects of drying and re-wetting on some mechanical properties of cortical bone. Journal of Biomechanics 21: 439–441.

Degrange, F.J.; Tambussi, C.P.; Moreno, K.; et al. (2010) Mechanical analysis of feeding behavior in the extinct “terror bird” Andalgalornis steulleti (Gruiformes: Phorusrhacidae). PLOS ONE 5: e11856.

Díez Díaz, V.; Mallison, H.; Asbach, P.; et al. (2021) Comparing surface digitization techniques in palaeontology using visual perceptual metrics and distance computations between 3D meshes. Palaeontology 64: 179–202.

Eng, C.M.; Lieberman, D.E.; Zink, K.D.; Peters, M.A. (2013) Bite force and occlusal stress production in hominin evolution. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 151: 544–557.

Erickson, G.M. & Olson, K.H. (1996) Bite marks attributable to Tyrannosaurus rex: preliminary description and implications. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16: 175–178.

Erickson, G.M.; Catanese, J. III; Keaveny, T.M. (2002) Evolution of the biomechanical material properties of the femur. The Anatomical Record 268: 115–124.

Erickson, G.M.; Gignac, P.M.; Lappin, A.K.; et al. (2014) A comparative analysis of ontogenetic bite‐force scaling among Crocodylia. Journal of Zoology 292: 48–55.

Erickson, G.M.; Gignac, P.M.; Steppan, S.J.; et al. (2012) Insights into the ecology and evolutionary success of crocodilians revealed through bite-force and tooth-pressure experimentation. PLOS ONE 7: e31781.

Figueirido, B.; Tucker, S.; Lautenschlager, S. (2024) Comparing cranial biomechanics between Barbourofelis fricki and Smilodon fatalis: is there a universal killing‐bite among saber‐toothed predators? The Anatomical Record: ar.25451.

Foffa, D.; Cuff, A.R.; Sassoon, J.; et al. (2014) Functional anatomy and feeding biomechanics of a giant Upper Jurassic pliosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from Weymouth Bay, Dorset, UK. Journal of Anatomy 225: 209–219.

Fry, J. (2019) Star Wars: the Galactic Explorer’s Guide. An Interactive Guide to Key Planets from The Star Wars Galaxy. Carlton Books, London.

Gignac, P.M. & Erickson, G.M. (2017) The biomechanics behind extreme osteophagy in Tyrannosaurus rex. Scientific Reports 7: 2012.

Haddara, M.M.; Haberisoni, J.B.; Trelles, M.; et al. (2020) Hippopotamus bite morbidity: a report of 11 cases from Burundi. Oxford Medical Case Reports 2020: omaa061.

Hirasawa, T. & Kuratani, S. (2018) Evolution of the muscular system in tetrapod limbs. Zoological Letters 4: 27.

Houssaye, A. (2022) Evolution: back to heavy bones in salty seas. Current Biology 32: R42–R44.

Huttenlocker, A.K.; Woodward, H.N.; Hall, B.K. (2013) The biology of bone. In: Padian, K. & Lamm, E. (Eds.) Bone Histology of Fossil Tetrapods: Advancing Methods, Analysis, and Interpretation. University of California Press, Berkeley. Pp. 13–34.

Lautenschlager, S. (2013) Cranial myology and bite force performance of Erlikosaurus andrewsi: a novel approach for digital muscle reconstructions. Journal of Anatomy 222: 260–272.

Lautenschlager, S. (2015) Estimating cranial musculoskeletal constraints in theropod dinosaurs. Royal Society Open Science 2: 150495.

Lautenschlager, S. (2016) Digital reconstruction of soft-tissue structures in fossils. The Paleontological Society Papers 22: 101–117.

Marquand, R. (1983) Return of the Jedi. 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, USA.

McHenry, C.R.; Wroe, S.; Clausen, P.D.; et al. (2007) Supermodeled sabercat, predatory behavior in Smilodon fatalis revealed by high-resolution 3D computer simulation. PNAS 104: 16010–16015.

Meers, M.B. (2002) Maximum bite force and prey size of Tyrannosaurus rex and their relationships to the inference of feeding behavior. Historical Biology 16: 1–12.

Perrin, S. (2022) The Rancor: Textbook Animal Cruelty. Available from: https://natureaccordingtosam.wordpress.com/2022/03/01/the-rancor-textbook-animal-cruelty/ (Date of access: 13/Jan/2025).

Porro, L.B.; Holliday, C.M.; Anapol, F.; et al. (2011) Free body analysis, beam mechanics, and finite element modeling of the mandible of Alligator mississippiensis. Journal of Morphology 272: 910–937.

Rahman, I.A. & Lautenschlager, S. (2016) Applications of three-dimensional box modeling to paleontological functional analysis. The Paleontological Society Papers 22: 119–132.

Rayfield, E.J. (2004) Cranial mechanics and feeding in Tyrannosaurus rex. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 271: 1451–1459.

Rayfield, E.J. (2007) Finite element analysis and understanding the biomechanics and evolution of living and fossil organisms. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 35: 541–576.

Favreau, J. & Rodriquez, R. (2022) The Book of Boba Fett. Chapter 3: The Streets of Mos Espa. Disney, USA.

Favreau, J. & Rodriquez, R. (2022) The Book of Boba Fett. Chapter 7: In the Name of Honour. Disney, USA.

Sakamoto, M. (2022) Estimating bite force in extinct dinosaurs using phylogenetically predicted physiological cross-sectional areas of jaw adductor muscles. PeerJ 10: e13731.

Sansweet, S.J. (1998) Star Wars Encyclopedia. Lucasbooks, USA.

Slater, G.J.; Figueirido, B.; Louis, L.; et al. (2010) Biomechanical consequences of rapid evolution in the polar bear lineage. PLOS ONE 5: e13870.

Snively, E.; Fahlke, J.M.; Welsh, R.C. (2015) Bone-breaking bite force of Basilosaurus isis (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Late Eocene of Egypt estimated by finite element analysis. PLOS ONE 10: e0118380.

Sutton, M.; Rahman, I.; Garwood, R. (2014) Techniques for Virtual Palaeontology. John Wiley & Sons, London.

Takaki, P.; Vieira, M.; Bommarito, S. (2014) Maximum bite force analysis in different age groups. International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology 18: 272–276.

Turner, C.H. & Burr, D.B. (1993) Basic biomechanical measurements of bone: a tutorial. Bone 14: 595–608.

Whitlatch, T. & Carrau, B. (2001) The Wildlife of Star Wars: A Field Guide. Chronicle Books, San Francisco.

Windham, R. (2007) Jedi vs. Sith: The Essential Guide to the Force. Del Rey, New York.

Wroe, S.; Huber, D.R.; Lowry, M.; et al. (2008) Three‐dimensional computer analysis of white shark jaw mechanics: how hard can a great white bite? Journal of Zoology 276: 336–342.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research received a generous grant from the Huttese Tatoonine Research Council (grant number THX1138). We received no funding from any Terran Research Funding agencies or the Galactic Empire Research Society.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Both are massive geeks, which heavily influenced the design of this study.

Dr Stephan Lautenschlager is an Associate Professor for Palaeobiology at the University of Birmingham, UK. Following a degree in software engineering he followed his passion for dinosaurs and other fossil organisms and became a palaeontologist. His research focusses on using digital methods and computer simulations to study fossil vertebrates. In his free time, he enjoys drawing, nature photography and looking after Minnie, the Chihuahua-Yorkshire Terrier mix (who provided moral support during the writing of the manuscript). You can find more about his research at https://stephanlautenschlager.com/

Dr Thomas Clements (he/him) is a postdoctoral researcher currently based in the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany. He is a ‘doctor of decay’: he specializes in understanding the post-mortem processes that organic remains have to undergo during the fossilisation process (the science of taphonomy). Outside of work, he spends his time painting models, helldiving, making videos, and being a full-time plant dad. You can follow Thomas’ research and news on his website (www.tgclements.com).